For hundreds of thousands of illegal immigrants, the path to the United States passes through the dense jungles, swamps, rivers, and slippery mud hills where South America ends and Central America begins. It is an unconquered, oppressive land that has for centuries rejected those who dared to penetrate its depths.

Today, it is the new gateway to the ‘Promised Land’ for many, driven by a determination born of desperation. They hope to get to the US by crossing the length of Central America and Mexico. It is one of the world’s most dangerous and ruthless migration routes.

They are weary travellers, their eyes bright with hope and fear, their hearts heavy with the weight of their dreams and a yearning for the lands they left behind. They are of all ages, from young teens to those in their 60s; there are families with pregnant women and children, and young, middle-aged, and old couples. They have been oppressed, mistreated, sexually abused, left hungry and without opportunities or hope in their own land. But they still have a smile on their faces. There is truly an innocence that breaks your heart.

They are Haitians, Venezuelans, Ecuadorians―some have walked across Brazil and into Chile. They have been stuck at borders between Peru and Brazil, and between Peru and Chile. They have, at times, been stuck for months in squalid conditions. Some have made it to Chile, and seen their dreams broken.

Many have walked across the Atacama Desert, hitchhiked, bussed, and otherwise made their way to the edge of the subcontinent. Now they are joined by downtrodden masses from Nepal, China, Laos, Cambodia, Bangladesh, Africa, and the Middle East. They all have the United States in their minds.

Many have been conned: They were told it was a short jungle trek; they have been charged all they can pay; some believe the US is just on the other side. But deep in their hearts they know better.

The heat is oppressive, suffocating and unrelenting. It seems as though the sun itself has made its home there. Darién is out to punish those who have the audacity to enter its realm. Though there is no road in this part of Colombia, Darién is the only break in the Pan-American highway that links the Americas from Alaska to Argentina’s tip at Tierra del Fuego. We are about to enter one of the world’s most difficult and treacherous places.

Under different circumstances, one could stop and take in the breathtaking nature, the forest ahead, the coral reefs on the Caribbean. We stand close to the northernmost part of Colombia, on the eastern side of the left-curving branch of land that connects the two subcontinents. The Panama border is a few kilometres northwest, the Pacific Ocean some 50km west, the Caribbean sea due north. The other side of the jungle is a 100km gauntlet through a vast wilderness teeming with dangers, desolation and the ether of death. It is a rough and bumpy boat ride to get there, among high winds and tall waves. It took six hours to cover the 270km across the Gulf of Urabá from Colombia’s Cartagena to Capurganá.

Many of the migrants are making their way to Capurganá from the town of Necocli on the coast of the Gulf of Urabá in Colombia’s Antioquia region; they have made their way there on foot and are now packing themselves in speedboats in numbers of 50 or more for the two-hour trip, and are arriving in Capurganá by the hundreds each day.

The beaches of Necoli now resemble the squalid camps where Haitians and Venezuelans gathered on the Brazil-Peru border just over two years ago. But the jungle-covered hills and turquoise waters with palm-fringed, remote fishing villages along the way are beautiful and picturesque, serene from the distance. It is not hard to imagine this could be the beginning of a new and beautiful life in America. Capurganá is one of those villages. There are no roads to get there and no cars, but small planes land there, servicing a tourist niche of nature lovers. It is a diving paradise.

But the tony hotels with lavish meals are not for you.

People are coming to the area in myriad small boats, most of them hungry like those making lines at the wall between Cuidad Juarez in Mexico’s Chihuahua state and El Paso, Texas. You have seen them on television. For many, this is where the journey to America really begins.

But it is a gaping chasm that separates this place from the Texas border―one treacherous, hostile, unpredictable odyssey across seven international borders fraught with extreme danger and exasperating uncertainty. And it starts with a dive into the most unforgiving jungle on earth.

A Venezuelan couple and their three-year-old son whispered silent prayers and crossed themselves, stopped for a second, looked up to the heavens, the woman kissed the child, held his head tight against her bosom, and they forged into the jungle and the perilous unknown, wearing new shoes. It is sad to say, but they were the only ones that stood out to memory among the thousands who start their journey north.

A group of Asians carrying their children and their belongings wrapped in makeshift plastic backpacks formed a crooked line into the Darién, their faces etched with lines of experience. Some of them forced a smile or perhaps they were just glimmering with hope, thinking of the paradise across the verdant abyss.They wear clothes with American logos, they have earrings, smartphones, and carry purses, backpacks, some even have pet dogs. Many have rosaries, scapulas and cross necklaces. It is surprising to see so many $100 bills and the cash they carry.

That is perhaps why many seem to fall victim to thugs, cartels and sinister factions looking for valuables and who submit the women to the added ordeals of sexual assault and violation.

When being robbed, the women say that the attackers insert their fingers in their intimate parts, looking for valuables. They are often taken by the outlaws and made to pay with their bodies for the passage of the men they don’t kill. These are not the shell-shocked refugees of war, but the experience is clearly one that takes a psychological, mental, and emotional toll.

A woman in her 40s, overweight and already struggling, trudges bravely―her ankles swollen and mosquito-bitten dozens times over. It is an endless stream of people, mostly single-lined along the roadless jungle, making paths at the cost of their bodies and their lives, scraping and cutting themselves, as a sudden hot rain turns the ground around their feet into slush, barely releasing each step. Ahead, loamy mud makes the rocks slippery and dangerous.

The border is at the top of the hill. For some, it is a feeling as that of conquering Everest. But in this no-man’s land, the border is merely a lonely handwritten sign, half-eaten by the jungle.

Then it sinks in. They are nowhere―thick jungle stretching out to the north, and to all sides the view is the same. No one is getting anywhere today. The five-hour trip many were promised is now a clear and cruel lie. It may be a few days to a week or more for those who make it.

Smugglers make money selling easy dreams. Cartels, drug traffickers, guerillas and an assortment of crooks and opportunists sell to these people the dream they want to buy. They are experts at telling them what they want to hear. If they don’t get their money, somebody else will. And if they don’t have money, they are not leaving.

The ones running this group of refugees, mostly fall into the latter category―organised local opportunists who take control of the arriving migrants as soon as their boat reaches land. They tag them with wrist bands, send them to shelters or onto the “guides”―smugglers or coyotes, really―who will charge them to lead them through the jungle.

Committed now, people are in the thick of the jungle on top of a hill many struggled to conquer. They are told they are in Panama, unofficially; there is no telling whether that marker is the actual border or just a cruel illusion created to give people the impression of progress, lest it stop others from paying to follow them.

It is now a slow highway of unprepared, disoriented people. Some fall, some break their bones, some get sick, some get lost, some die. Reminders of those possibilities come often, in the form of fluttering rags of what was once clothing around living people, now just a few bones.

Death is very real here. It could come by accident, by illness, by deadly animal or insect bites, or by people who rob and sexually abuse and decide to kill for fear, or for fun. If this jungle has a law, these gunlords are it.

Emmanuel Houngbédji of Cotonou, Benin, has been walking with Omar and Fatima, a Bangladeshi couple in their 30s who are afraid to give their last names. Fatima is pregnant and Omar has carried her through the swamps and up the hills. Emmanuel has been carrying their stuff on top of his, it includes a cooking pot, a burner and a gallon of water. They did not have the money to get to Panama by boat, so they are paying Emmanuel to help them get through on foot.

Most people travel only with their countrymen. Most are Haitian. The dense forest and rugged terrain of the Darién have made it virtually impassable for centuries. With no roads or established crossings, it has for centuries been considered virtually impassable. The few paths and trails seen there in the 1960s were said to belong to isolated, hostile tribes that had no contact with the outside world, and the myths and legends that made their way back were of encounters with cannibals and hungry beasts.

In the 1970s and 1980s, incursions by drug traffickers and guerrillas gave the area a reputation of a wild, lawless place where violence was a dangerous reality. In popular perception, it became the impenetrable barrier between South America and the North.

In the years since, largely through the brutal work of cartels and smugglers, some paths have been opened across the gap. They have cost countless lives, but have also created a lucrative route for people smuggling and migrant trafficking.

Now, criminal groups run the show. This territory and routes are controlled by the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC) and the Gulf Clan, known in Colombia as Clan del Golfo, a powerful drug cartel and one of the largest criminal organisations in the country. They have opened strategic routes for moving drugs.

The paramilitary cartel is known for its use of violence and intimidation to maintain control over territories and drug routes. Indeed, there were people walking the gap, whispered to be drug mules. But it is a whisper that could cost your life. The cartels can be brutal.

So many have been making the exhausting and dangerous journey on foot under the oppressive, unrelenting heat, enduring an air that is so dense with humidity that it clings to the body like a tight, suffocating blanket. Swarms of buzzing, relentless insects assailed the stream of people making their way through the jungle, leaving trails of bites and welts on the body, but that was nothing compared with the venomous snakes, painful bullet ants, poison dart frogs, crocodiles, spiders, and even jaguars that could be poised to strike the moment you stray or drop your guard.

Through the rain-soaked leaves and the constant attack and danger from unseen creatures, the migrants slip and fall, dislocate their joints and scrape their flesh. In this group, the elderly are carried by others, the younger wounded ones are passed by the rest. It is hard to see, and harder to ignore.

The journey is hard, it is dangerous, it is daunting. Rivers rise, currents separate families, and children are lost. Steep hills are a muddy slush that at once suck you in and slide you down. Like a green Everest, the climb is gruelling and tough. It is a formidable challenge, and there are women with children, some pregnant, babies, men with swollen limbs, young men out of breath, battered. And the tracks are dotted with skulls and clothing of those who did not make it.

Slippery rocks coated with the remnants of rain are a constant threat, they could send one tumbling onto the jungle floor where everything from sharp rocks to venomous snakes await. Everyone knows they have to get to a clearing to make camp and survive the night.

The nights are humid and stifling, oppressive with their warmth. As darkness comes, the insects come alive, they buzz ceaselessly, biting and persisting, tormenting the senses. It is dark and it swallows you into a great void, the only thing that helps people get through is the flicker of a better future. They know they are following steps of those who came before them and made it through, or so they hope.

The humanitarian need is such that Médecins Sans Frontières (Doctors Without Borders) has set up assistance camps halfway through the unforgiving jungle labyrinth. The MST camp at Bajo Chiquito in the Panamanian Darién is in a remote and secluded community in the middle of the untamed wilderness. It is a rugged and demanding place, yet it is an island of respite for the injured, worn-out, hungry and battered migrants. MST says it has provided over 50,000 medical consultations, helping the wet, weak and bewildered travellers.

Gashed limbs, injuries from falls, serious intestinal problems from dehydration and drinking dirty river water, infections, skin lacerations and bug bites, stings, ankle and foot problems and festering blisters are things they see every day. Pregnant women, too.

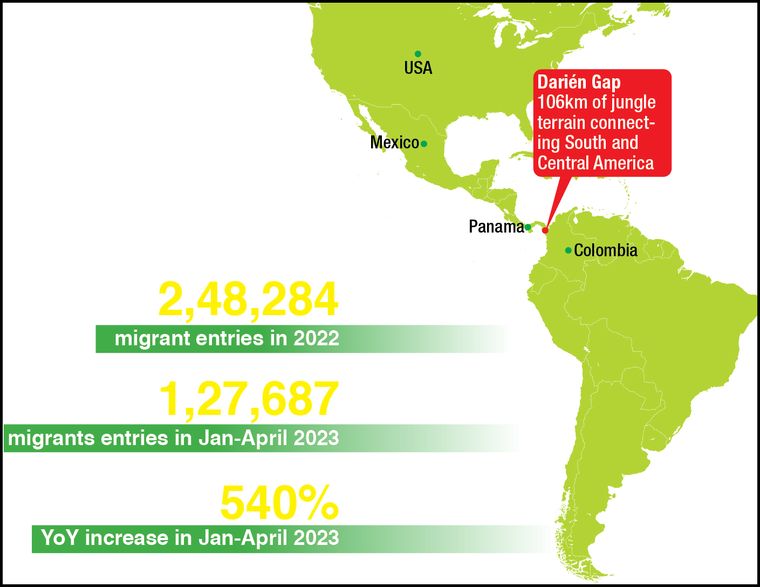

According to records from the Panamanian migration department, in 2022, as many migrants passed through the Darién as they have in the past 12 years. And the number, about 2.5 lakh, was nearly the double of the 2021 numbers. This year, the numbers are already several times higher than in the same period last year.

According to the United Nation’s International Organization for Migration and its Missing Migrants Project, 36 people died in the Darién last year. That number is most certainly missing those whose remains speckle the jungle; the remains tell the fragmented story of anguished deaths, their frozen poses evincing the desolation at their last moments on earth. “Deep in the jungle, robbery, rape, and human trafficking are as dangerous as wild animals, insects and the absolute lack of safe drinking water,” said a UNICEF press release in 2021, quoting its regional director director, Jean Gough. “Week after week, more children are dying, losing their parents, or getting separated from their relatives while on this perilous journey,” said Gough, estimating that as much as half of the children who cross the Darién are under five.

According to UNICEF estimates, at least a thousand children were unaccompanied or separated last year. MSF says that beyond the gruelling physical experience, the toll of seeing corpses and injured people left behind to be consumed by the jungle adds a psychologically damaging component.

Yet, it is not the only thing that haunts their journey. Lurking shadows of armed factions cast a sinister pall over their passage. Exploitation, robbery, violence and the menace of human trafficking threaten to shatter their hopes and inflict untold suffering upon their vulnerable souls.

But the American dream is a powerful magnet and despite the warnings about the arduous 100km trek across the Darién’s six lakh untamed hectares plus another 4,000km through seven countries to get to Texas, perhaps only to be arrested and deported, the allure remains strong and steadfast among the throngs of new people “yearning to be free”.

For humans, dreams never die.

At the base camp, I learn the name of the child of the Venezuelan couple. It is not a boy; her name is Adriana. She is smiling, and there is a sparkle in her parents’ eyes.