Annirudhsinh Chudasama of Dholera, Gujarat; Vinayak Naik of Genaiyyanvade, Karnataka; Godson of Periyathura, Kerala; and Stephan of Kanyakumari, Tamil Nadu, do not know each other. But there is something common to all of them—they are all victims of the vagaries of the Arabian Sea.

Chudasama’s land became barren because of the salinity ingress. Naik watched as seawater rushed into his paddy fields and submerged them. Godson, like hundreds of other traditional fishermen from Kerala, stopped going to the sea as the catch was getting meagre by the day. And, Stephan lost his home to the sea.

In the past, the Arabian Sea was calm, as seas go. But not anymore; the frequency and intensity of cyclones have increased multi-fold in the last decade.

The west coast of India has been hit with mutiple “severe intensity” and “very severe intensity” cyclones since the disastrous Cyclone Ockhi in 2017. Cyclone Ockhi took form on November 29, 2017, and left a trail of destruction in the Lakshadweep archipelago and the southernmost districts of Tamil Nadu and Kerala. Cyclone Ockhi was followed by Cyclone Vayu (June 2019), Cyclone Kyarr (Oct-Nov 2019), Cyclone Nisarga (June 2020) and Cyclone Tauktae (May 2021). Formed close to Lakshadweep, Tauktae travelled up to the Gujarat coast and retained its fury for 24 hours after landfall. It brought severe rains over parts of Rajasthan, Delhi and even Uttar Pradesh.

“The Arabian Sea is no longer what it used to be,” said Roxy Mathew Koll, senior scientist at the Indian Institute of Tropical Meteorology (IITM), Pune. He pointed out that a colder sea surface prevents the formation of cyclones. “The Arabian Sea is getting warmer than other tropical ocean basins,” he said. “It was less prone to cyclonic storms earlier because it was colder than the adjacent regions. This change manifests mainly in the form of depressions and more frequent cyclones.”

Data from IITM shows a 52 per cent increase in the number of cyclones in the Arabian Sea between 2001 and 2019. An 8 per cent decrease was observed in the number of cyclones in the Bay of Bengal during the same period. The most visible manifestations of the warming up of the Arabian Sea would be droughts and extreme rainfall events. “We are already experiencing all that,” said Koll.

As per the Union government, 2,002 persons were killed in hydro-meteorological events (cyclones, heavy rains, floods or landslides) in 2021 alone. Agriculture crops in 50.4 lakh hectares were destroyed last year because of extreme weather events. Dr Jitendra Singh, minister of state (independent charge) of science and technology and earth sciences, told Parliament in December 2021 that climate change and rising temperatures are kicking up more and more cyclones in the Arabian Sea. “Analysis of data from 1891 to 2020 indicates that the number of cyclones and the number of stations reporting very heavy and extremely heavy rainfall events have increased in recent years,” he said.

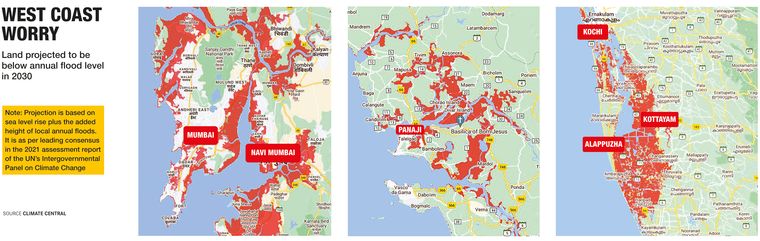

As the sea is getting warmer, there is a corresponding rise in the sea level, too. This is more apparent on India’s western seaboard than on the east.

“Coastal cities like Mumbai and Kochi are expected to be hit hard by compound events like sea-level rise, storm surges, and coastal erosion,” said S. Abhilash, director, Advanced Centre for Atmospheric Radar Research, CUSAT, Kochi. “Combined with these would be the extreme rainfall events, flash floods, and higher water run-off from the land. What we see in the form of increased instances of depressions, coastal erosion and flash floods are all wake-up calls indicating a climate emergency.”

The fisher communities are the worst hit. There is massive drop in catch, especially pelagic fishes. Bhavin Kotia, 35, a Porbandar-based boat owner lamented that while a fishing trip demanded an outlay of Rs5 lakh, the catch would only be worth Rs3.5 lakh. “This has been happening quite frequently now,” he said. “I have six boats. I cannot afford these losses.”

Most fishermen are now compelled to venture into deeper waters—which means more days at sea and more expenses on a single trip. On top of it is the reduction in the number of fishing days due to extreme weather conditions.

“Our coastal belts are under severe strain, as the fishermen are at a loss on how to deal with the changes in the Arabian Sea,” said Fr Peter Darwin, former parish priest of Vallavilai in Kanyakumari district, Tamil Nadu. “Their traditional wisdom about the sea is no longer helping them as there have been changes in wind patterns, resources and currents.”

According to researchers, the warming up of the sea is taking a huge toll on the marine ecosystem as the presence of phytoplankton—the major food source for pelagic fishes—has fallen by 20 per cent. The Arabian Sea had been one of the most phytoplankton-rich seas in the world and that was the reason behind the generous catches in the region.

Fr Darwin added that fishermen are compelled to spend months together in the outer sea these days, which in turn has affected their social and personal lives. “The lives in the coastal belt are going through a very rough patch,” he said. “They are losing the trust they had in the sea.”

If the coastal belt is the primary victim of the changes in the Arabian Sea, the hinterland is not far behind.

“We are facing frequent cyclones,” said Pratap Khistarya, a farmer residing near Porbandar. “The monsoon is erratic. Crops are damaged, and it is difficult to fetch a good price.” He added that small farmers cannot bear these losses, and most of them will end up working as farm labourers.

The cultivable lands and wells close to the coastal areas are increasingly becoming saline. The rising tides have started to flood paddy fields that are kilometres away from the seashore. The lands are becoming barren. Chudasama says he lost 15 bigha land over the last couple of years to salinity ingress. Showing a vast stretch of land in Mandvipura of Bhavnagar district, he added that villagers in the area were rehabilitated to other hamlets several years ago, as sea levels rose.

“What happens in the sea affects the land and what happens on the land affects the sea,” said Srikumar Chattopadhyay, former head of the Resources Analysis Division, National Centre for Earth Science Studies.

Every expert whom THE WEEK met said that all the problems that are happening due to the changes in the Arabian Sea are only going to intensify in the coming days.

Koll said that the only way forward was to adapt to better survival techniques. “Calamities are for certain. We can survive that only with better risk mapping at a micro level,” he said.

The role of human interventions in turning the Arabian Sea into what it is today is equally significant as the larger culprit: climate change. “It is easy to blame everything on climate change as if it is a faceless behemoth sitting somewhere far away. But the reality is that every individual can play a role in stopping the world from reaching a tipping point,” said John Kurien, visiting professor, School of Development, Azim Premji University. “Every artificial port constructed, every plastic bottle thrown into the sea, every amount of pollutant flown into the sea beds, every unscientific method of fishing, every dam built on the rivers, every hilltop broken for quarrying and every act of deforestation will have an impact on the sea. The sea has been absorbing all the terrestrial sins flowing into it all these years. But how long can the sea take it?”

Chattopadhyay says that the solution lies in the hands of every individual. “There will be no aspect of our lives that will be unaffected by the changes happening in our oceans,” he said. According to him, even small steps like planting more trees to harvesting rainwater will have cumulative effects in the long run. “Micro-level planning is equally important as the macro-level ones,” he said.

With inputs from Nandini Oza and Prathima Nandakumar