An Iruliga tribesman wades into a muddy puddle inside a kilometre-long subterranean aqueduct near Bengaluru. He is fearless, but wears a mask, which is now mandatory in the world above him. In this darkness, his only source of light is his mobile phone torch. It is an abandoned aqueduct, built decades ago. He and a companion are here to catch bats. Iruligas are hunter-gatherers who eat bats. While many people blame the winged mammals for the Covid-19 pandemic, and fear them, the tribe continues to treat them just as before—as food. A heap of bat droppings in the middle of the tunnel indicates that there was a large colony of bats here, before they fell prey to the tribesmen.

M. Byregowda did his doctoral studies on the tribe. He is also in “contact” with bats, but for a different reason. He collects decomposed bat droppings to use as fertiliser for the fruit trees and vegetables plants on his farm. He says no modern fertiliser can match bat-compost in agricultural yield. Bats also help in pollination and pest control, so he happily permits bats to feast on the fruits on his farm. “The bats are taking their share,” he says, “because they contributed to growing these fruits.”

Rescuers from the Avian and Reptile Rehabilitation Centre (ARRC), Bengaluru, save more than one hundred bats every year, from urban areas. Most of their calls have been related to bats harmed by man-made entrapments, such as power lines or kite strings. But, this year, the ARRC is receiving calls from concerned citizens asking it to remove the bats which roost on their roofs. “We try to convince people that these pipistrelle bats are harmless and [explain their] contribution to controlling insects, but people are still worried because of the bad press that bats got during the pandemic,” says Jayanthi Kallam, founder and executive director of the centre.

During the pandemic, bat researcher Rohit Chakravarty bust many a myth about bats through his educational videos on social media. Chakravarty, who is currently working on his doctoral thesis at the Leibniz Institute for Zoo and Wildlife Research, Germany, says that reductions in bat populations can drastically affect human health and economy. “Bats have lived close to humans for centuries, contributing massively to food and cash crop production and insect control,” he says.

Almost all animals harbour viruses. But, bats have an exceptional immune system, which prevents them from falling ill from most viruses. Thus, they become hosts. There is no proof that the novel coronavirus spread from bats; they are ‘prosecuted’ purely on suspicion. Bats rarely spread diseases directly to humans. They need a medium, like an intermediate animal, to pass on a disease, most of the time. And the cause of most zoonotic diseases is unsustainable human interaction with nature (for example, uncontrolled agricultural intensification and urbanisation, exploitation of wildlife and climate change).

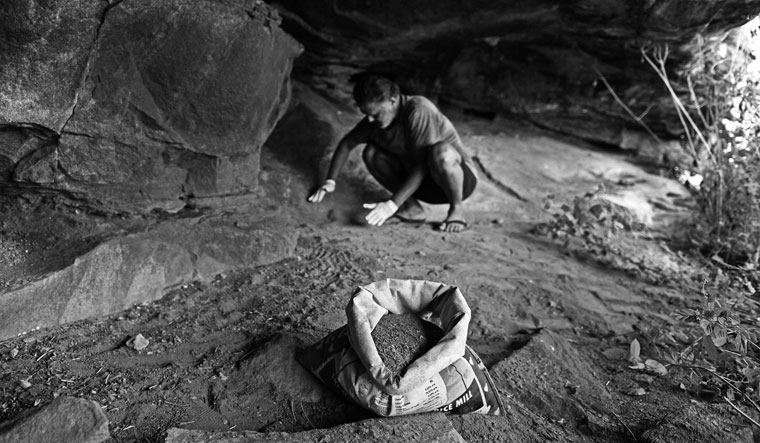

Iruliga means people who live in the dark. Before they were relocated to government-built homes, they were living in caves, with bats. If bats are so harmful, how did the tribe survive? When it comes to knowledge of bats, it is the ‘enlightened’ city dweller who is in the dark. If humans, in our greed, eliminate the space between nature and ourselves, calamities are inevitable. Let there be space.

Bat facts

There are around 1,400 species of bats

They are the second most common mammals, after rodents

They are the only flying mammals

Some bats use vision for navigation, but most use echolocation

They host many viruses, but are immune to the effects of most

Their immune system is a major area of interest for researchers

Bat wings have skin-like membranes, which can recover if damaged

Though seen quarrelling, they are social; mothers carry pups during flight

Salim Ali fruit bat and Wroughton’s free-tailed bat are classified as endangered in India