The essence of the “Putin doctrine” is this: “Russia Matters”. The west, however, sees Russian President Vladimir Putin as an inscrutable, stealthy and sinister Cold War ninja. His grievance is that since the Cold War ended, a triumphalist west has neither treated Russia with respect nor taken its security concerns seriously. Instead, NATO has steadily advanced into Russia’s “sphere of influence”. William Burns, CIA director and former US ambassador to Russia, warned that Ukraine’s entry into NATO would be the “brightest of all redlines for Putin”.

To signal that he will invade Ukraine if this redline is crossed, Putin has more than a lakh soldiers almost encircling the country and has forced the US to the negotiating table. Said Russian foreign policy expert Andrei Kortunov, “The military buildup is aimed at getting Washington’s attention and he has got it.” President Joe Biden said he expected Russia to invade Ukraine in February. Admiral Sir Antony David Radakin, the UK’s chief of the defence staff, warned that a Russian invasion “would be on a scale not seen in Europe since World War II.” There would be mass casualties, waves of refugees and occupation or partitioning of Ukraine.

The US and Britain have evacuated all non-essential staff from their embassies in Kyiv. But Europeans do not share the Anglo-American threat assessments. Their staff remain in Ukraine. To America’s embarrassment, Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky, too, did not agree that an invasion was imminent and urged everyone, including Biden, to calm down as war cries were spooking investors.

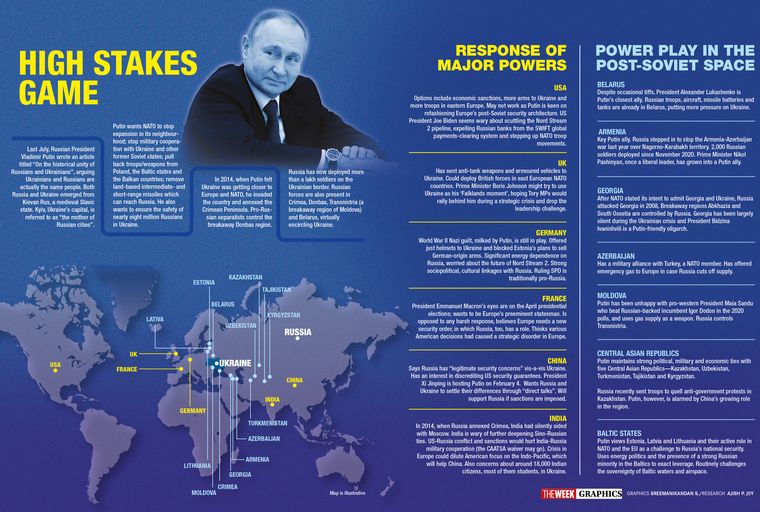

Experts continue to debate what Putin really wants in Ukraine. Russian military expert Dmitri Trenin said Putin was not keen on annexing more territory, and that his aim was to stop NATO’s expansion. Putin wants to bring Ukraine back into the Russian orbit and he believes that “true sovereignty of Ukraine is possible only in partnership with Russia”. Whether Putin invades or not depends on western concessions to his demands, which includes halting NATO’s eastward enlargement, freezing further expansion of its military infrastructure in the former Soviet territory, ending western military assistance to Ukraine and removing intermediate-range missiles in Europe.

NATO dismissed the maximalist demands as a “non-starter”. If anything, it began fast-tracking Romania’s long-pending request to have a NATO battlegroup, like Poland and the Baltic countries have. Said a European diplomat, “The west is not threatened by Russia as in the days of the Cold War, but it cannot afford the perception of defeat.” Biden has talked the carrot-and-stick language of diplomacy and deterrence, but striking a deal is hard because it would make him look as if he caved in to the Russian strongman.

Ukraine’s chance of joining NATO is dim, as not all members are enthusiastic. They do not wish to alienate Russia or to wage a war in Ukraine. NATO’s collective defence doctrine, which means that an attack against one ally is considered as an attack against all, is a huge burden. Two months ago, the US state department officials reportedly told Ukraine that its NATO membership was unlikely to be approved in the next decade. “Despite the western media’s predilection for depicting Putin as reckless, he is cautious and calculating, particularly when it comes to the use of force,” said Trenin. But by amassing troops, Putin has raised the stakes for NATO’s continued eastward expansion.

The Soviet Union’s collapse enabled NATO’s unchecked expansion into the former Soviet republics, the Baltics and eastern Europe. Released from Moscow’s political and military grip, these countries yearned for western-style democracy, freedom and prosperity. But Putin was convinced that the pro-democracy revolutions in Georgia and Ukraine were CIA-inspired. At the 2007 Munich Security conference, Putin asked rhetorically, “We have the right to ask, ‘Against whom is this expansion directed?’”

Even some NATO members had misgivings about the expansion. In 1994, when the four Visegrád countries—the Czech Republic, Poland, Hungary and Slovakia—were joining the alliance, US president Bill Clinton warned that NATO could not “afford to draw a new line between the east and the west that would create a self-fulfilling prophecy of future confrontation”.

NATO’s announcement at the Bucharest summit held in April 2008 that Georgia and Ukraine were aspiring members ratcheted up Putin’s threat perceptions. “This was like poking the bear with a stick,” said Alan West, member of the House of Lords and former head of the Royal Navy. Putin invaded Georgia four months later and seized Ossetia. In 2014, he annexed Ukraine’s Crimea, home to Russia’s Black Sea Fleet. He also seized Ukraine’s eastern region of Donbas that borders Russia. Putin asserted that he would not stomach Ukraine being turned into “a springboard against Russia”.

For Putin, now is a good time to crash the Ukrainian springboard. The US is deeply polarised, its politics dysfunctional and its president weak. Moreover, its international stature is dented by the Afghanistan pullout. Seasoned Putin is dealing with his fifth US president. Europe is divided when it comes to relations with Russia. Eastern states like Poland and the Baltics fear a resurgent Russia, while Germany seeks cooperation.

Author and Russia expert John Lough outlines the deep commercial, political, cultural and intellectual networks between German and Russian elites. Britain, meanwhile, threatens severe sanctions and flexes muscles in tandem with the US on Russia, but the Boris Johnson government is keen to protect “Londongrad”, so nicknamed due to the huge investments by Russian oligarchs in the British capital. Both Biden and Johnson are battling domestic crises. Europe is also mired in domestic challenges. Oil and natural gas exports give Russia considerable leverage over a Europe reeling under high energy prices.

Russia has another trump card—China. US sanctions have brought the two countries closer. Ukraine is to Russia what Taiwan is to China. The greatest 21st century foreign policy challenge for the US is its strategic rival China, not Russia. Fighting both is hardly smart. To China’s advantage, Biden is likely to be preoccupied with Russia. Analysts say that should war erupt in Ukraine, it will weaken Russia, the US and Europe. The only one to emerge stronger will be China.

Integral to the Putin doctrine is the belief that the post-Cold War liberal order has run its course and the future is likely to be a multipolar world with the US, Europe, Russia and China each with its own “sphere of influence”. Putin has inspired authoritarian leaders worldwide. As recent events in Belarus and Kazakhstan show, Russia is the go-to power for embattled autocrats.

A keen student of history, Putin sees 2022 as the perfect year to launch his “Russia Matters” doctrine. The year marks the centenary of the founding of the Soviet Union. Putin sees Russia as the natural heir of the Soviet state. To make Russia great again, he wants to reassert Russian hegemony in erstwhile Soviet republics and regain influence at the global decision-making table.

Russia has strengths—an advanced military with hypersonic missiles, nuclear weapons and veto power in the UN. It is also an energy and technology powerhouse. Still, today’s Russia pales in comparison with Soviet Union. Its economy is about the size of Italy’s. To make up for Russia’s inferiority to the US in conventional military and economic might, Putin must be “innovative, catch the west off guard and fight dirty,” said Fiona Hill, who has worked for three American presidents. Putin projects himself as a macho, shirtless, Cold War pin-up commando. But he is also a hybrid warrior and a cyber ninja, modernising the Soviet bag of tricks and treats, employing spinmeisters, fanning divisions, poisoning defectors, spreading disinformation and spinning conspiracies.

To say Putin sows discord in the west would be giving him too much credit. These differences pre-date Putin. Spawned in troll farms, Russia has weaponised American social media platforms and technologies to drive fringe ideas into the mainstream, making fractiousness more visible and vocal. Russian email hacks, ransomware attacks, cyber wars on infrastructure grids, banks, governments, legislatures and interference in western elections have been well-documented. Putin has supported anti-American and Eurosceptic groups in Europe, backed far left and right populist movements and abetted private sector’s thirst for profit. Despite their political leaders’ disapproval, Italian and German business delegations recently met Putin at the Kremlin.

The west sees Putin as a wily, divide-and-rule chess player who plots far ahead. Nobody wants war, not even the Russians. But dissent is muted, if not silent. “Putin’s Russia is a one-man show,” said Hill. Over the past 20 years, Putin has strengthened himself—quashing dissent, enriching his coffers and entrenching himself by amending the constitution to potentially remain president until 2036. If fate bows to his will, Putin has enough time to implement his doctrine for the world to acknowledge that “Russia Matters”.