IN MY OWN MEMORY, strangely, there's no record of pain.

I remember lying on the floor watching the pool of my blood spreading outward from my body. That’s a lot of blood, I thought.

And then I thought: I’m dying. It didn’t feel dramatic, or particularly awful. It just felt probable. Yes, that was very likely what was happening. It felt matter-of-fact.

It’s rare for anyone to be able to describe a near-death experience. Let me say first what did not happen. There was nothing supernatural about it. No “tunnel of light.” No feeling of rising out of my body. In fact, I have rarely felt so strongly connected to my body. My body was dying and it was taking me with it. It was an intensely physical sensation. Later, when I was out of danger, I would ask myself, who or what did I think the “me” was, the self that was in the body but was not the body, the thing that the philosopher Gilbert Ryle once called “the ghost in the machine.” I have never believed in the immortality of the soul, and my experience at Chautauqua seemed to confirm that. The “me,” whatever or whoever it was, was certainly on the edge of death along with the body that contained it. I had sometimes said, half-humorously, that our sense of a noncorporeal “me” or “I” might mean that we possessed a mortal soul, an entity or consciousness that ended along with our physical existence. I now think that maybe that isn’t entirely a joke.

As I lay on the floor, I wasn’t thinking about any of that. What occupied my thoughts, and was hard to bear, was the idea that I would die far away from the people I loved, in the company of strangers. What I felt most strongly was a profound loneliness. I would never see Eliza again. I would never see my sons again, or my sister, or her daughters.

Somebody tell them, I was trying to say. I don’t know if anyone heard me, or understood. My voice sounded far away from me, croaky, halting, blurry, inexact.

I could see as through a glass darkly. I could hear, indistinctly. There was a lot of noise. I was aware of a group of people surrounding me, arching over me, all shouting at the same time. A rackety dome of human beings, enclosing my prone form. A cloche, in food-world terminology. As if I were the main course on a platter―served bloody, saignant―and they were keeping me warm―keeping, so to speak, the lid on me.

I need to talk about pain, because on this subject my own recollections differ considerably from the memories of those around me, a group which contained at least two doctors who had been in the audience. Members of this group said to journalists that I was wailing with pain, that I kept asking, What’s wrong with my hand? It hurts so much! In my own memory, strangely, there’s no record of pain. Maybe shock and bewilderment overpower the mind’s perception of agony. I don’t know.

It’s as if a disconnect had appeared between my “outward,” in-the-world self, which was wailing, et cetera, and my “inward,” within-myself self, which was somehow detached from my senses and was, I now think, close to delirious.

Red Rum is murder backward.―Red Rum, a horse, won Grand National Steeplechase three times.―’73, ’74, ’77.―This is the kind of random nonsense that was cropping up between my ears. But I did hear some of what was being said above my head.

“Cut his clothes off so we can see where the wounds are,” somebody shouted.

Oh, I thought, my nice Ralph Lauren suit.

Then there were scissors―or maybe a knife, I really have no idea―and my clothes were being torn off me; there were things that people really needed to attend to urgently. There were also things I needed to say.

“My credit cards are in that pocket,” I mumbled to whoever might be paying attention. “My house keys are in the other pocket.”

I heard a man’s voice saying, What does it matter.

Then a second voice, Of course it matters, don’t you know who this is.

It was probable that I was dying, so what did it matter, indeed. I didn’t expect to need house keys or credit cards.

But now, looking back, hearing my broken voice insist on those things, the things of my normal everyday life, I think that a part of me―some battling part deep within―simply had no plan to die, and fully intended to use those keys and cards again, in the future, on whose existence that inner part of me was insisting with all the will it possessed.

Some part of me whispering, Live. Live.

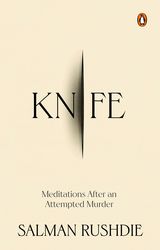

Excerpted with due permission from KNIFE by Salman Rushdie, published by Penguin Random House India. © Salman Rushdie, 2024.

Knife―Meditations After an Attempted Murder

By Salman Rushdie

Published by Penguin Random House India

Price Rs699; pages 209