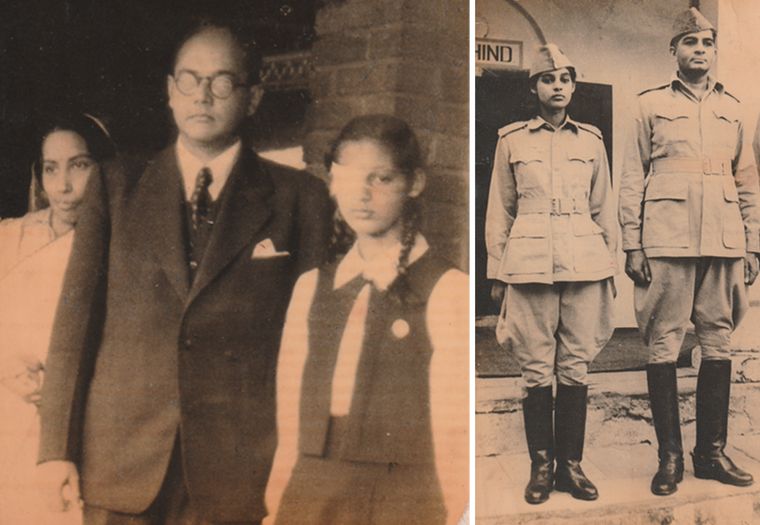

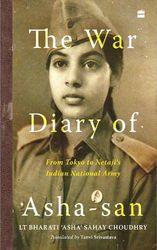

It is noon. The sky outside the window is a dusty, December barely-blue. Lieutenant Bharati ‘Asha’ Sahay Choudhry emerges from the warmth of her thick quilt―post her morning nap in her Patna home―in a white patterned kimono. Her hair, the colour of the moon, is held back neatly with four clips. Her hands, which once held a rifle as part of her training with the Rani of Jhansi Regiment, now holds a walker.

At 95, she is one of the oldest published writers in India. The War Diary of Asha-san chronicles the life of a girl growing up in war-torn Japan, fighting her own battle for the freedom of her country. “Ma would not let me sleep if I had not written in my diary,” she says. “We could not only write the good. You had to write the good and the bad.” Written in Japanese, on scraps of paper, and translated into English by Tanvi Srivastava (her great granddaughter-in-law), it has been published by Harper Collins India. Ask her what was the bad that the diary chronicled and she smiles: “We used to lie to ma. When enemy aircraft swarmed, ma would tell us to go into the trench. We would not listen and [instead] watched the dog fight. When American [aircraft] fell, we would celebrate. They were our enemies then. How to kill the British was the motto.”

On June 15, 1943, a red-letter Tuesday in her diary, she met Subhas Chandra Bose and her life changed. “Netaji was in Japan,” she says. “I wanted to meet him. It was forbidden to go out at night, but we went at midnight. We reached the Imperial Hotel. He was standing there. I bent down to touch his feet. He told me that I should never bend. ‘You stand up and say Jai Hind. We have always bent under the British. Now, no more bowing. You have to fight for independence.’’’

This is a story that she has narrated countless times. And one that has been passed down as a family heirloom, lovingly polished each time. “It was a personal journey for me as well,’’ says Srivastava. “Before I read the diary of Asha San, I had heard her stories. But, when I read the diary and the everyday details, I got goosebumps.”

Over 80 years later, Asha’s passion is still palpable. Her eyes are clear, her voice thinner with age, but her spirit is still very much of the teen that signed up to train to kill. “Nothing was ever difficult,’’ she says. “I was happy that we could use the rifle and learn it. We used to march and hold the rifle”. Her bayonet eviscerated Winston Churchill. (Not the man, but an effigy made of sack. The Ranis’ training included running 10 steps and on the eleventh shouting Jai Hind while piercing the effigy). “I learnt the bayonet but didn’t get the opportunity to use it,” she says.

Her diary―lyrical, vivid and engaging―is the coming-of-age story of a girl who trained to fight, “to look the enemy in the eye’’, but her “war ended before it began’’. “My rifle did not fire any bullets, my bayonet did not slash the arteries of any enemies,’’ she says. The bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, the Japanese surrender and the death of Bose ended the mission.

At the time Bose suggested the idea of women in combat, it was nothing short of radical. If Mahatma Gandhi pushed women out of homes to free India, Bose went further―to the frontier. The Ranis were trained in handling rifles, anti-aircraft guns, and methods of warfare, including guerrilla warfare. “I return home at seven in the evening,” writes Asha. “Ma doesn’t give me any work anymore. ‘Arrey baba, if you cut your hand here, how will you work there? Netaji’s soldier will hold a gun in her hand, not a flower.’’’

The war for India’s freedom was also a personal battle for freedom. Even if she did not know it then. “No one forced me,’’ she says. “I said I wanted to go.’’ After Japan’s surrender, Asha was imprisoned in Singapore. “There was no trouble in jail,” she says. “We used to laugh and sing ‘Kadam Kadam’. The Indians who came would send us food.” The song would become the bedtime song for her kids and even years later her voice may crack on the high notes.

Asha may not have found a place in history, but her diary has found its way to bookshelves and has carved out space to accommodate women like her. While history books still have men as the heroes and women as supporting actors, big publishing companies are at the heart of independent stories like Asha’s and are adding furiously to them. This year alone, the space has been widened to include a whole spectrum.

Sara Rai’s Raw Umber―the story of her family set in Allahabad, where the presence of her grandfather, writer Premchand, remained―was evocative and intimate. Meeran Chadha Borwankar’s Madam Commissioner recounts the memories of being the only woman officer in her batch of 1981 and of tackling the underworld. The upcoming biography of Vijaya Lakshmi Pandit―a diplomat and very much a woman about town, admired even by Marlon Brando―by Manu Bhargavan adds to this growing trend. But it goes beyond just conventional history.

Fabulous Feasts, Fables and Family by Tabinda Jalil-Burney is about food, growing up in Aligarh where kebabs made memories and stories. The book is about recipes, but also about childhood.

Then there is Ritu Menon’s India on Their Minds―8 Women, 8 Ideas of India. In a slim volume, Menon tells the story of women who witnessed the independence struggle, participated in it and shaped it―whether it was through their writing, like Ismat Chughtai, Attia Hosain, Nayantara Sahgal and Qurratulain Hyder, or directly, as Captain Lakshmi Sahgal, Kamlaben Patel, Rashid Jahan and Sarla Devi Chaudhurani did. Each of these women grappled with freedom as they fought for it. As publisher to all of them, Menon’s book is intimate as well as essential, especially at a time when the idea of India is being pitted against Bharat.

After translating Asha’s story, Srivastava is now rescuing the story of Asha’s mother, Sati Sen. The niece of freedom fighter and barrister C.R. Das had rebellion in her blood. In school, she was sent home by the nuns for singing God Shave the King. She blamed it on her Bengali accent. She married Anand Mohan Sahay. It was a love marriage, amid opposition. The two moved to Japan to fight for the revolution. In Kobe, when Indians decided to hoist the tricolour on January 26, 1935, Sati found that three Indian houses had chosen to fly the Union Jack. She set off with matches and set them on fire. The Japanese refused to arrest her saying that she was a patriot.

“Even her husband in his memoirs just mentions her in passing,’’ says Srivastava, who is researching her story in archives to find the Indian National Army files. “I found her diary,’’ she says. “Here was this woman who was away in Japan but was connected to India. She writes about Jallianwala Bagh in 1922, and even though she was far away, she felt so strongly. You can feel the power.”

Like Srivastava, Anita Mani, too, has tried to flesh out women who are often only footnotes. Her book, Women in the Wild: Stories of India’s Most Brilliant Women Wildlife Marine Biologists, has brought to life the remarkable story of Jamal Ara―possibly the first Asian woman ornithologist. Ara, who studied only till class 10, wrote a book which is very much a bible for bird watchers. But, apart from the name little was known about her. “We did not even know she was a woman,’’ says Mani. But, a piece by a young essayist helped connect her story. If Ara had been lost in time, others in Mani’s book are pioneers who have never been acknowledged, like J. Vijaya, India’s first female herpetologist and turtle field biologist, who died at 28. Viji, as she was known, was ahead of her times―a tom boy who carried a bag of crocodile scat in a bus. “The trigger for me was Viji,’’ says Mani. “It took a while to piece together her life.” But now that it is out there, like Asha’s, it is impossible to erase.