On March 10, the trailer of Anubhav Sinha’s Bheed was released. Shot entirely in monochrome, it told the story of the 2020 lockdown and its devastating impact on thousands of migrant workers. It pulled no punches as it laid bare caste and class equations and apathy from the top. Within three days, the trailer was pulled. A meeker one came up, scrubbed clean of the “controversial” references. First to go was Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s announcement of the lockdown. Then the visuals showing the police raining lathis on migrant workers. By the time the film released, there were 13 additional modifications and cuts―all references to the government were removed. The film lost its essence.

For Sinha, known for making films “with a voice”, like Mulk and Article 15, this was heartbreaking. “The biggest risk was telling the story of the tragedy itself, but that was the very reason I wanted to make this film,” he said. “You should not brush misfortunes under the rug. I make the film that I want to make and feel intensely about it. Making a film and completing it is in itself an accomplishment (these days). The other half of the accomplishment is making a film exactly the way you want to because there is so much that goes on.”

This “so much that goes on” includes, more and more so, a push to make films that align with the ideology of the ruling class.

In the past two years, the Hindi film industry has churned out more than 20 films that feature, if not promote, the majoritarian narrative. This covers concepts like nationalism and hindutva, and includes films such as The Kashmir Files, Samrat Prithviraj, Ram Setu, Code Name: Tiranga and Brahmastra Part One: Shiva.

“The right wing is flexing its muscle and has managed to make some films to suit its agenda,” said Ranjini Mazumdar, professor of cinema studies at the School of Arts and Aesthetics, Jawaharlal Nehru University. “It is true that the RSS is interested in changing the space of popular cinema to reflect its own propaganda.”

This year, on January 30―the day Mahatma Gandhi was killed in 1948―director Rajkumar Santoshi released Gandhi Godse, Ek Yudh, a film that allows Nathuram Godse to explain his ideology and justify his actions, and takes a dig at Gandhi for his “fake fasts” and “lack of empathy”. The film re-imagines history, where Gandhi and Godse walk in a world where both can coexist.

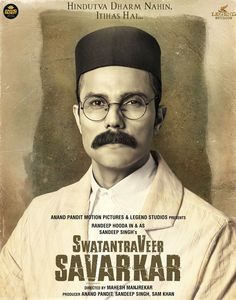

Just four months into 2023, the Hindi film industry has more than ten such big-budget, big-banner films lined up. There is the Randeep Hooda-led Swatantra Veer Savarkar, Ae Watan Mere Watan produced by Karan Johar, Yodha starring Sidharth Malhotra, a take on the Ramayan featuring Prabhas called Adipurush, and Meghna Gulzar’s Sam Bahadur with Vicky Kaushal as Sam Manekshaw.

Lower down the industry ladder are more blatant projects. Like Dr Hedgewar, a biopic on the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh founder, which is scheduled to release on Dussehra. Union Minister Nitin Gadkari clapped off the movie, which will be shown in villages across India as part of the RSS’s centenary celebrations starting 2024.

Then there is Main Deendayal Hun, featuring Annu Kapoor as Pandit Deendayal Upadhyaya, an ideologue of the Bharatiya Jana Sangh, the forerunner of the BJP. Kapoor and producer Ranjeet Sharma reportedly visited RSS leader Indresh Kumar at his house in Delhi’s Paharganj to seek his inputs for the script. Pawan Nagpal, who is directing, had also helmed last year’s Bal Naren, in which a teenager who sells tea when not in school uses a cleanliness drive to stop the spread of Covid-19 in his village.

“We are only getting started,” said Atul Sharma (name changed), an RSS functionary from Mumbai, on the condition of anonymity. “You will see many more of these in times to come. We have started discussing with Bollywood directors and scriptwriters as to how we can further our idea of Hindustan. How we can make sure our children grow up to learn the right things about their own nation. It is our duty to emphasise Indian culture and the best way to do it is to get cinema to do the talking.”

The association of films with politics is not new, said Srinivas S.V., professor of cinema studies at Azim Premji University, but added that we are now seeing “a new kind” of propaganda film. He cited the example of Ram Setu, which stars Akshay Kumar, the poster boy of such cinema. “In more ways than one, Ram Setu feels like a cultural manifesto of the saffron brigade with its emphasis on faith above everything else,” he said. “This film clearly drew on the political mobilisation around the controversy relating to the Sethusamudram Project and it is an attempt to invoke religious fervour.”

He also brought up this year’s Samrat Prithviraj, again starring Kumar. “The film showed a divisive and saffronised history in relation to the Hindu king Prithviraj Chauhan,” said Srinivas. “The film shows Chauhan killing Muhammad Ghori, but a basic internet search shows that Ghori was killed by his own men.”

Earlier films like Padmaavat and Tanhaji: The Unsung Warrior had also played up the good Hindu versus evil Muslim idea and had tried to equate religion with nationalism.

Though this type of cinema has been around for a few years, it reached its peak last year with The Kashmir Files, which talked about the brutal Kashmiri Pandit exodus from the valley. It is said to have made more than Rs300 crore. Director Vivek Agnihotri, who at the time was criticised for being generous with facts, told THE WEEK: “In Sholay, do you think there should have been a point of view of Gabbar Singh and his family? Do you think there should have been a Nazi point of view in Schindler’s List? It has to be only the victim’s point of view because there are only two kinds of people in this world―those who kill and those who don’t. They are terrorists and I will not provide any ideological support to them.”

Researcher Saurabh Pandey, who was responsible for putting down “relevant content into the script”, said his brief was simple: “Show the suffering of Hindus. Nothing else mattered and nothing else was to be deemed important.”

Even the blockbuster Pathaan―which fans celebrated as redemption for Shah Rukh Khan after he was hounded by a section of hindutva supporters―“follows the agenda, albeit subtly”, claimed Sharma. “First, the entire plot is weaved around the abrogation of Article 370,” he said. “The film says it loud and clear, as if it’s a message to Pakistan that Kashmir will never be up for discussion. Second, it shows a high-ranking military officer (Dimple Kapadia’s Nandini) invoking a Hindu deity as she sacrifices herself for the nation, thus equating religion with nationalism.”

Sharma, though, was quick to add, “We are not in the business of making policies and definitely not those that curb the creative liberty of filmmakers. But then, we have to show them a direction as to how to project India. We need to highlight the Hindu way of life and what the Hindu leaders have done for us.”

Around the world, mainstream cinema has always reflected prevailing public opinion. “Except that, till 2014, the dominant discourse in India was largely that of secularism and unity in diversity, and we had films that reflected that spirit,” actor Swara Bhasker told THE WEEK. “We have had Amar Akbar Anthony, Mani Ratnam’s Bombay and even films like Refugee, Veer-Zaara and Jodhaa Akbar, which became mass entertainers with ‘Hindu-Muslim unity’ at their core. After 2014, you suddenly see much of Bollywood parroting the sangh agenda. So you have films like the biopic of Modi or The Accidental Prime Minister, which was character assassination of Manmohan Singh. Then there was the vulgar and violent Kashmir Files and Tanhaji, which no historian worth his salt would call history. The tragedy is that one cannot make a film in Bollywood with a Hindu-Muslim romance in today’s India.”

One of the first major indicators of pressure on the Hindi industry came in 2016. Dharma films was targeted for casting Pakistani actor Fawad Khan in the romantic drama Ae Dil Hai Mushkil. Such was the fear that director Karan Johar went on record to say that he would not work with Pakistani talent in future.

“The reason Bollywood is kowtowing more than usual is because when it doesn’t, then the result is cuts, bans and major losses,” said Bhasker, whose own career seems to have suffered because of her political ideology. “Any popular medium will try to match public sentiment, but when the public sentiment is so vitiated, then obviously you will see that reflected in films. The reason the south [film industry] is free of this is because four of the five south Indian states are ruled by non-BJP governments and the RSS has not really been able to penetrate into the region except for Karnataka. If the dynamics change in the south, the same thing will happen there, too.”

The film industry has always been vulnerable to government action given the number of permissions one needs to release a film. Add to that the threat of being dragged to court over any tiny “controversy”, and filmmakers and producers would want to play it safe. “Given that budgets are increasing, a producer wouldn’t want to fight a six-month court case with the government to prove a point,” said Bhasker. “No businessman will do it. In any case, the box office is unpredictable. So, even if they might personally disagree with the RSS position, it makes more sense for them to quietly toe the line.”

Asked if this was the case, veteran director Sudhir Mishra―whose upcoming thriller Afwaah talks about films being boycotted and filmmakers being trolled―said, “Even if it is true, I don’t see any problem if someone wants to make a pro-government film. All films should compete in the open market. A lot of people are scared and they move with a lot of trepidation. We are soft targets. Everybody uses the film industry to score points and distract the public. I think it is ridiculous the way the industry is knocked around. Everything in this world is permissible as long as it does not lead to harm. There are no holy cows.”

Filmmaker Shekhar Kapur, whose latest What’s Love Got to Do with It? has just come to India, has been watching the industry from a distance for some time now. “Tell me, when did we not have restrictions on our creative liberties? My Bandit Queen was banned by the censor before it went on to become one of the most successful films of its time,” he said. “And that was the time of the Congress. So, how far are you willing to fight? That’s what matters.”

Director Hansal Mehta, whose recent movie Faraaz kicked off a debate on Islamic fundamentalism―the movie pits the “good Muslim” against the “bad” one―said cinema was a creative institution that should be allowed to function free of politics. “Nobody can tell us what films to make,” he asserted.

Some other filmmakers, though, admit to treading cautiously. For instance, Aasmaan Bhardwaj, who recently directed Kuttey under his filmmaker father Vishal Bhardwaj’s tutelage, said he was unsure about making a film based on the book he is currently reading. “I know I will not be able to make it in our country because of the prevailing political climate,” he said. The book is In an Ideal World by Kunal Basu, which explores the themes of politics and fanaticism in India today.

The Hindi film industry, which through the years has mirrored the Indian growth story, talked about the Nehruvian dream of prosperity from the 1950s to the 1970s, took to narrating stories of an aspiring middle class in the 1990s through the early millennium, and has now been furthering the Hindu nation-making project in a bid to appease Hindu nationalists, said Namrata Sathe Rele, a professor who completed her PhD in cinema studies from the Southern Illinois University in the US. “We have come to a stage where,” she said, “we cannot even imagine in our wildest dreams that we will ever get to see another Bombay or Veer-Zaara in these times.”