In the north of India exists a land that is the heart of the country’s inkiest darkness. It measures just one-tenth of India, but conjures up trouble far bigger than its size. Here, most inhabitants have lost, or, perhaps, never held a moral compass; while the few with shreds of soul lack gumption. The inhabitants of this land are mostly politicians, criminals or policemen―or their lackeys. The others (teachers, shopkeepers, office-goers) do not count. Here, not a single sentence is complete without an expletive. Here, women are either ready to be trod upon, or scheming vixens.

Here, there is no middle path―though it is where Gautama Buddha walked. Here, there are no people like us.

This land of extremes is but an alternative universe created by online streaming platforms. On a map, you can identify this universe as the states of Uttar Pradesh and Bihar. But that is just a geographical placement; for the alternate OTT universe exists wholly neither in society and the culture nor in the art and language of this region’s life.

So which big bang birthed this alternative universe?

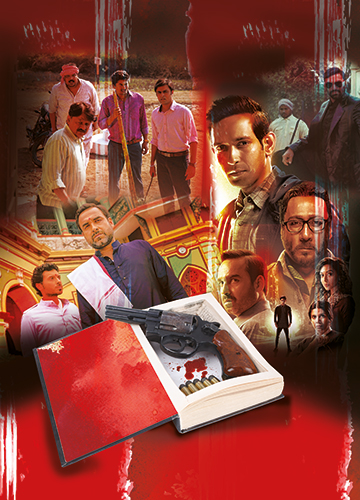

In 2018, Amazon Prime released the first edition of a series called Mirzapur, which drew its name from a district (neighbouring Varanasi) famous for its rugs and carpets. Its handwoven, world famous products have a geographical indication tag―but that is a story for another day.

In the first 20 minutes of episode one of Mirzapur, references are made to body parts and pubic hair; female characters giggle to suggestions of the aftermath of swaying anatomies; a man loses two fingers to a faulty country-made firearm, which backfires; betel leaf-chewing teachers generously fire projectiles of red juice into dustbins and cuss words are liberally exchanged.

Mirzapur was a monstrous hit. By the time its second season was out in 2019, the district’s MP Anupriya Patel (now Union minister of state for commerce and industry) made known her displeasure at her constituency’s negative portrayal. But the series had set an unusually tawdry bar, which others had by then raced to grab.

Pankaj Tripathi, who headlined Mirzapur, was born in Gopalganj, Bihar, before moving to the National School of Drama in Delhi. Tripathi’s talent strides across mediums (his last theatrical release was Laal Singh Chaddha in 2022). Asked how he rated the portrayal of his state on OTT platforms, he denied having watched any Bihar-based series.

“UP and Bihar have always had this problem of perception. They are just like any other state. Bihar’s gross state domestic product might be low, but its emotional and intelligence quotient is high. Half of those who clear the Union Public Services Commission (UPSC) exams come from here. There was a time when caste violence was dominant, people would protest and that made news. The outside world would see that as adbhud [amazing, but negative],” said Tripathi.

The real life Tripathi comes through a little bit in Criminal Justice (2019, Hotstar) in which he plays an astute lawyer of Bihari origin. “A maker must exercise some self-restraint,” he said, on the excesses in the world of OTT.

Lucknow born and educated Aahana Kumra (Call my Agent: Bollywood, Netflix, 2021) has had to deal with a different fight of perception. “I have been told I look too modern, too urban, too smart to be cast in a series on UP,” she said. Going by those undisclosed standards, did UP girl and Miss India Runner Up 2021, Manya Singh look or not look UP-enough? And, was the Lucknow educated Ritu Karidhal Srivastava, deputy operations director to India’s Mangalyaan Mission, too smart to have come from the state?

The OTT space is highly regarded as it offers the freedom to tell stories without the pressures of censorship. But like any other art, it has succumbed to its hit genres and tropes. Series like Panchayat (2020, Amazon Prime), which depict the trials of an engineering graduate who, unwillingly, takes up the job of a panchayat secretary in a UP village, are too few.

The UP and Bihar most OTT content portrays is, at best, a slice of eastern UP contiguous with Bihar. To imagine that all of those who inhabit UP and Bihar speak only in a predominately eastern dialect is a stretch too far.

That the same filmmaker can craft three completely different stories, all from the same region, is demonstrated beautifully by Muzaffar Ali, one of Lucknow’s best loved directors. Ali’s first film Gaman (1978) looked at the pain of a migrant from UP who struggles to settle in Mumbai. Then, in 1981 came Umrao Jaan, the story of a Lucknow courtesan. Five years later, he made Anjuman (the film did not have a theatrical release), which put under the lens the challenges faced by makers of Lucknow’s famed chikankari embroidery.

Amit Sial (Jamtara, 2020 Netflix) who is from Kanpur, a city once called the Manchester of the East, said, “Crime and sex attract everyone. I don’t know why, but we are stuck in it. OTT was to be a platform where something different could be tried. However, that is mostly lost. A producer or director will look for a writer who writes crime well, but they now need to scout for those who write un-crime well,” he said. Notice that made up word he uses: un-crime.

As a UP born, Sial knows its people better. So when he was cast as the bowler Devender Mishra in Inside Edge (2017)―the first Hindi series distributed by Amazon Originals, he suggested to the makers that instead of pegging him as a character from western UP, they let him be from Kanpur. Once that was agreed upon, he said, he could flow with the character―incorporating the quirks, mannerisms, frustrations and angst that he had seen growing up.

Not all crime stories from UP/Bihar are fictional. In true stories, such as Raktanchal (2020, MXPlayer) which is centred around the mafia wars of eastern UP and Bihar, the geography itself is a character. Thus, its use is completely fair. But what when names are used only to titillate the audience?

Sitapur: City of Gangsters for instance is just any crime story that could have been told anywhere. Did Sitapur appear in its title just to assure its audience that the north Indian level of blood and gore would be presented?

Anil Rastogi is a retired scientist from Lucknow’s Central Drug Research Institute and a highly regarded theatre and television artist whose web credits include Aashram (2020, MXPlayer). “Sitapur was shot as a web series. I couldn’t understand why so much sex, violence and bad language had to be a part of it because it contributed nothing to the story,” said Rastogi, “I refused to speak certain lines. For some reason the series was turned into a film and all the vulgarity edited out.” So yes, the story could be told without its excesses. Rastogi said that he was immensely uncomfortable watching his own work, precisely because of these extremes.

Gopal Sinha, who retired from the state’s electricity department, is an active theatre artist; he has directed 10 plays, acted in 70 but spent the most time doing light work on stage. Sinha said that despite Lucknow having a wide pool of artistes, series makers stuck to a select few. “Money does not matter to me above creative satisfaction. Makers choose from those who do not have the option to say no, or to put forth their own viewpoints. And, thus, the same faces repeatedly perpetuate the same myths about the state. They (makers) need to pick those faces and shoot in UP to qualify for the generous subsidy the government offers.”

At the 68th National Film Awards in October 2022, UP won a special mention award for the most film friendly state. But is the state’s well-thought-out film policy dragging its image through grime?

While portraying the bad men of UP’s wild east, why not a series on Raghupati Sahay, one of the greatest Urdu poets of all times, who, as inherent in his pen name―Firaq Gorakhpuri―is from that same area of crime? Why not a series on the ancient Nalanda, the site of the world’s first residential international university built in 427 CE in what was then Magadha (modern Bihar)? The flexibility of the OTT space is the best medium to explore a telling of such stories in contemporary settings.

Very rarely, however, streaming platforms turn saviours for stories that must be told. In 2021, Lucknow-born Munzir Naqvi completed a film called Sehar, which looked at the demonisation of Urdu. Central UP (erstwhile Awadh) of today is still a region where the version of Hindi spoken is Hindustani. That language is a delightful mix of Hindi and Urdu, sprinkled with Persian and Arabic influences. The protagonist of Naqvi’s film, a Kashmiri Pandit professor who teaches Urdu at a Lucknow college, is the enormously talented Pankaj Kapur. The conflict comes from the closure of the department where Kapur’s character has taught for decades.

Sehar made it to some film festivals, including the Asian Film Festival at Barcelona and the Dhaka International Film festival. However, it failed to get through the censors for a theatrical release. There is no answer as to why―but perhaps in the times we live in, there is an othering of Urdu. It does not wholly belong to us.

Naqvi’s film will finally be available some months from now on a streaming platform. But shorn of the mandatory doses of violence, nudity and profanity expected from UP, its reception is uncertain.

Naqvi said, “There is a blind following of genres. North India is portrayed as lawless territory―almost a war zone. Everyone wants to be part of this chaos. But for how long will the land of Ram be portrayed as the Lanka of Ravan?”

India’s dark heart would definitely like an answer to that.