In July 1948, thousands of Palestinian men, women and children left their homes in Ramla and Lydda fearing brutalities from Israel, the Jewish state that had come into being on May 14, 1948. Soon, these ancient towns that lay between Tel Aviv and Jerusalem, outside the Jewish state designated in the UN Partition Plan of 1947, were swarmed with Jewish immigrants who returned to their “promised land” from different parts of the world. And, the cities’ character transformed from predominantly Arab to Jewish. In the last six decades, the Jewish state systematically erased much of the evidence of the Palestinian expulsion from Ramla, including stories of the city’s Muslim past.

When Jerusalem-based artist Meydad Eliyahu started researching his solo exhibition ‘Copper Wing’—which is currently on at the Contemporary Art Centre, Ramla—he found a striking similarity between the city’s history and that of his own Cochini Jew community. Eliyahu’s forefathers made the aliyah (immigration to Israel) from Kochi, Kerala, in 1954. “I saw a parallel in the way history was repressed in the case of Ramla as well as in the case of the Cochini community,” he says. “However, the Jewish state alone is not responsible, but the community itself played a part [in erasing its Indian past] to merge with the general population.”

Cochini Jews, also known as Malabari Jews, are considered to be the oldest Jewish sect in the Indian subcontinent. They came to the Malabar coast via ancient trade routes and flourished as a community. When Israel was formed, most of the community members immigrated to the new country. However, they suffered humiliation and prejudice there.

Eliyahu says the immigration also brought dramatic changes in the community. “They immigrated from Kerala, a land that is fertile and with so much greenery, to be resettled in an undeveloped desert land, where there were no trees or water, but only rocks and sand,” he says. “But Cochini Jews convinced themselves that they should put aside their Indian past. They stopped living their lives as Indian or Malayali.”

The artist cites an example from his own family. His father was one of the earliest to marry outside the strongly endogamous Cochini community. “My mother was born in Israel, and she was not from a Cochini family,” says Eliyahu. “My parents were one of the earliest mixed couples in the community. My father wanted a more ‘Israeli’ way of living, and he found a nice partner outside the community.”

It was while working on his 2016 project, ‘The Box of Documents’, that Eliyahu started obsessively searching for his roots. The “big silence” from his father’s family about their lives in Kochi led him on a quest to find the missing links. During his research, Eliyahu explored and learned about many unrecognised traditions and forgotten historical events of his community. In his latest exhibition—’Copper Wing’—he proposes a place for these traditions in the Israeli cultural milieu. ‘Copper Wing’ also challenges the narrow perception of India in Israel—only as a “spiritual” place, or as a centre for yoga or drugs. The kind of cultural richness that Indian Jews brought to Israel has been forgotten.

Eliyahu dedicated ‘Copper Wing’ to the memory of his father, Avaraham, who died while Eliyahu was preparing for the exhibition. Avaraham was just six when the family—a wealthy and influential one among the Jews of Kochi—made its aliyah. They settled in a moshav (cooperative agriculture settlement) in Mesillat Zion. Avaraham grew up to become a public figure in the community. “My father knew Malayalam. So, he used to translate for elders [who were not proficient in Hebrew]; he helped them to communicate with the Israeli bureaucracy,” says Eliyahu. “He was like a bridge for them. He was a bridge for me also; one that connected me to the Indian culture.”

Eliyahu uses a cashew curtain as an important motif in ‘Copper Wing’, something that he associates with a particular memory about his father, Ramla and India. “Every time my father went to Ramla, he used to bring back cashews,” says Eliyahu. “Kerala is known for cashews. So, for me, it was symbolic; I felt that buying cashews was my father’s way of reconnecting with Kerala via Ramla—where there is the presence of all four Indian Jewish communities.”

The cashew curtain installation is made of copper cut-outs. At the centre of the exhibition space is a hollow pipe with a rough surface. This installation simulates the idea of a trunk that leads to “other spaces which may even be imagined expanses”. It is inspired by the trunks of Ramla’s palm trees and Kerala’s coconut trees.

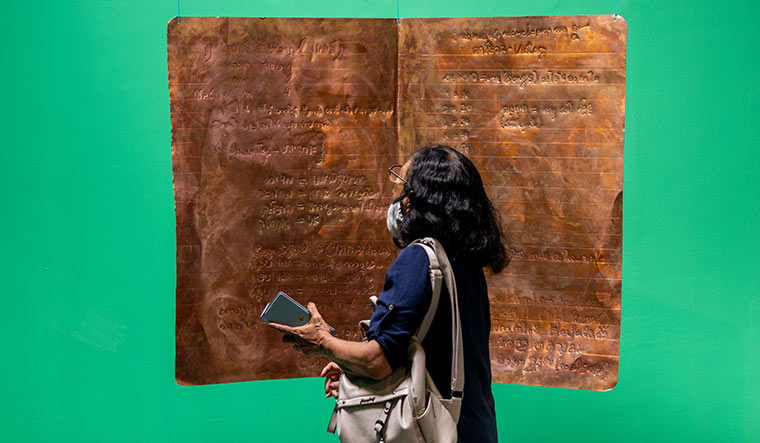

Another important installation in the exhibition is an open notebook made out of a copper plate, with texts in Hebrew, English and Malayalam. It was inspired by a notebook Eliyahu saw when he visited a Cochini Jew family in Ramla. The notebook belonged to the late Esther Tiferet, who had left Kerala in the 1970s, and spoke only English and Malayalam. “She translated Hebrew terms into English and Malayalam, and noted them down in her book,” says Eliyahu. The notebook was a testimony to the pain and effort of his people to get integrated into the Israeli state. The choice of the copper plate as the medium was also a conscious decision, says Eliyahu. It refers to the Jewish Copper Plates of Cochin, a royal charter of privileges issued by the Chera king Bhaskara Ravi Varma to Joseph Rabban, a Jewish merchant and community leader, almost a millennium ago.

Eliyahu sees culture and visual art as effective tools to prevent homogenisation and ensure diversity. The artist adds that ‘Copper Wing’ offers an “emotional, spiritual and meditative” experience to visitors who come from diverse backgrounds.