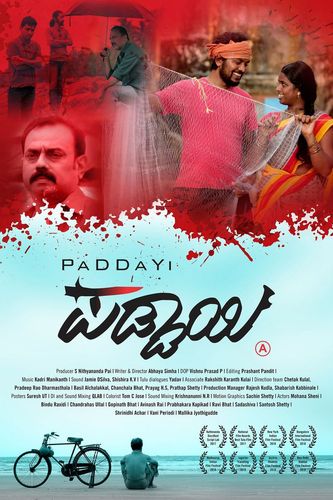

In the national award-winning Tulu film Paddayi (2018) by Abhaya Simha, Madhava and Sugandhi, a newly-wed couple in coastal Karnataka, bring physical and psychological harm upon themselves, perhaps misreading a prophecy of Babbarya Daiva—the guardian deity of the Mogaveera (fishermen) community. The film is a retelling of William Shakespeare’s Macbeth.

Paddayi was screened along with three other award-winning Tulu films—Madipu (2017), Bangar Patler (1993) and Gaggara (2010)—at the 13th Bengaluru International Film Festival held in early March in a tribute to the Tulu film industry which turned 50 in February 2021.

The five-decade-long journey of Tulu cinema (also known as Coastalwood) is a story of creative excellence as much as it is of resilience. Its first film, Enna Thangadi by S.R. Rajan, released in 1971; its first national award came in 1993, Bangar Patler. Since then, Tulu cinema has got six national awards and around 15 state awards. After S.R. Rajan, many stalwarts like K.N. Tailor, T.A. Srinivas, Richard Castelino, Ram Shetty and Sanjeeva Dandekeri forayed into Tulu filmmaking.

Karavali or coastal Karnataka is the land where the daiva (divine spirit) is revered as much as the deva (God). Tulu is spoken in the coastal districts of Dakshina Kannada and Udupi in Karnataka and parts of Kasaragod in Kerala. The 2011 census estimates that 20 lakh people speak Tulu; linguists studying dying languages identify it as a “vulnerable” one.

However, Tulu language is a treasure trove of Tulu oral literature, tradition and culture, replete with beliefs and rituals that are interwoven into the lives of the Tuluvas. It derives from natakas (plays), night-long performances of yakshagana (traditional folk theatre), and of course, cinema, which has provided a new dimension and expression to the cultural brew of Tulunadu.

While the first colour film was made in India as early as 1937 (Kisan Kanya) and in Karnataka in 1964 (Amarashilpi Jakanachari), the first Tulu film in colour (Kariyani Kattandi Kandani) was produced by Aroor Bhimaraomade only in 1978, as lack of both funding and access to the technology compelled Tulu filmmakers to make movies only in black and white.

Soon, however, filmmakers started experimenting with scripts and technology. The Tulu film, September 8, directed by Richard Castelino, was shot in a day in Mangaluru, creating a record in world cinema. Castelino had used nine cameras with nine units at different locations to complete the film in record time. It did not do well at the box office though. Another similar experiment, Gaggara, by actor-director Shivadhwaj Shetty, won the national award in 2010. It was shot in 10 days on a shoestring budget of 010 lakh.

“In 2011, Tulu cinema again started picking up pace and new trends emerged with a new generation of filmmakers foraying into the industry,” says Tamma Lakshmana, an art director who has been chronicling Tulu cinema in the last decade. “Covid-19 has been a major setback to the industry. It will take some time for it to recover and get back on track. Post pandemic, lifestyles have changed and the industry too should reinvent itself.”

Lakshmana, who has tracked the 50 years of Tulu cinema in his yet-to-be-published book, feels Tulu cinema is at an interesting turning point. “It began its journey anchored to the flourishing Tulu theatre, which is still hugely popular,” he says. “Today, it is expanding its market and audience base beyond the coastal region as it is being patronised in Bengaluru, Mumbai and the Gulf countries. Earlier, we could not carry the boxes of reel to overseas audiences. But with the advent of digital technology, we are now able to reach out to new markets.”

Chethan Mundadi, who won a national award for his debut film, Madipu, shares Lakshmana’s views. “I worked as an art director for Kannada serials and reality shows,” he says. “When I decided to make a film, I closely studied super-hit Kannada films of the 1970s and 1980s, especially those of Dr Rajkumar. I found that in all these films, the story was king and not the hero. Today’s films are being made for the hero, where the story just seems incidental. I always felt movies should be thought-provoking and not simply be watched and forgotten. The USP of Tulu cinema is the storylines that adhere closely to the Tulu ethos.”

Tulu actor and producer Shivadhwaj Shetty flags shortage of theatres, high tariff and competition from other languages as hurdles to the growth of the Tulu film industry. While single-screen theatres are not viable for low-budget Tulu films, as they charge a fixed rent on a weekly basis irrespective of the collection, the multiplexes work on a percentage basis and demand higher share in overall revenues. Restrictions on the number of screens to release non-Kannada films, and the higher tariff for screening “other regional language” films have been detrimental to Tulu cinema.

“The average budget for a Tulu film is between Rs45-60 lakh. But the return on investment is not encouraging, owing to a restricted market. However, many producers are coming forward to make films out of passion for Tulu cinema,” says Shetty, adding that OTT platforms can help expand the reach of Tulu cinema.

“The pandemic had its silver lining, too, as older Tulu films that had been overlooked got an audience on OTT. But Tulu films have to compete with other language films like Hindi, Kannada, Telugu and Tamil. While subtitles and dubbing rights help us expand, the action and horror thriller genres which are in great demand turn out to be too expensive for us to make,” explains Shetty.

Mundadi adds that smaller OTT platforms do not have a wide reach and the bigger ones like Netflix and Amazon Prime pay only meagre amounts for film rights. The government should build dedicated theatres to promote films in regional languages like Tulu, Kodava and also Kannada, he says. “The lifeline for Tulu cinema is the Tulu audience. OTT can only prolong the life of the cinema. Only when the movies are watched in theatres do they become commercially viable for the producer,” says Lakshmana. “Our films used to run for more than 100 days. But today, it is difficult to see houseful shows.”