When I was two, Mahatma Gandhi was travelling from Bengaluru to Mysuru to collect 'Harijan fund'. My brother-in-law V.T. Thammaiah asked me to hand over a small amount as donation. But Gandhiji refused to accept the money and instead asked him to part with the gold earrings I was wearing. And we readily gave him the earrings," writes former external affairs minister S.M. Krishna in his recently released autobiography, Smriti Vahini. It is written in Kannada.

It was the former Karnataka chief minister's refined speech, impeccable dressing sense, flair for music, books and tennis, and his transforming of the sleepy town of Bengaluru into a global IT hub that define his five-decade-long stint in politics.

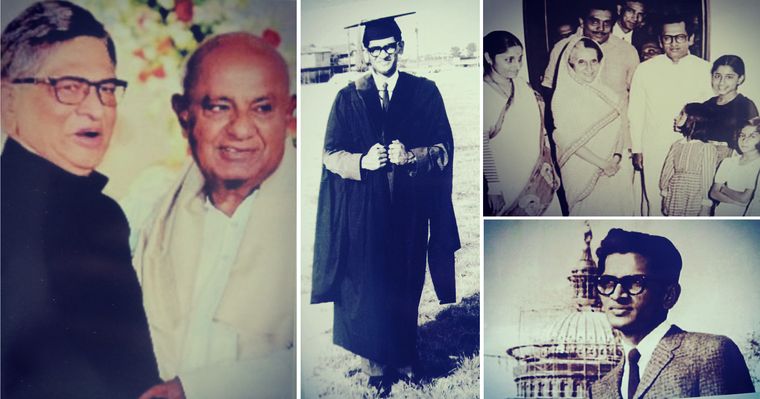

In January, Krishna Patha—a bouquet of six books that chronicles his political journey—was released. Of these, Smriti Vahini, is a compilation of conversations between Krishna and his scholar friend Pavagada Prakash Rao, who recorded 200 hours of conversations with Krishna when he was governor of Maharashtra. A compilation of essays (Statesman) by 130 intellectuals who have known Krishna and photographs (Chitra Deepa Saalu) are also part of the bouquet.

In Smriti Vahini, Krishna talks about his formative years as a public figure. In Krishna's second year in college, he contested the student union elections but lost by 57 votes. "We had a separate ballot box for boys and girls. Out of the 100 girls, 97 had voted for me! I won the next student elections," recounts Krishna. The respect he had for women was always mutual. It was in Krishna's cabinet that the most number of women became ministers in Karnataka, with four being inducted in 1999.

Krishna, a Fulbright scholar, studied law in Texas. In September 1960, Krishna wrote to John F. Kennedy, who was running for presidency, expressing his desire to run his poll campaign in localities that had sizeable population of Indians. Kennedy obliged. "Kennedy, like Nehru, liked to mingle with the common man," writes Krishna. "He gave priority to development and social justice. After he won, Kennedy sent me a letter to thank me," recalls Krishna, who considered Kennedy his political guru.

Recalling Indira Gandhi's campaign in Mandya in 1971, Krishna says she had a magnetic personality. "At 53, she enthusiastically walked around the stadium to greet the huge crowd, before getting on to the dais. I was only 37, but failed to keep pace with her," he says. He became the industries minister in the Devaraj Urs-led state government (1972-77), within a year of becoming an MP.

The socialist movement in India suffered due to the ego of its leaders, notes Krishna, adding that it was Jayaprakash Narayan who united the opposition against the Congress. "[A.B.] Vajpayee and [L.K.] Advani were in Bangalore to take part in the parliamentary committee meeting when the Emergency was declared," says Krishna. "I was hosting them for dinner at Hotel Ashoka, as I was a state minister. At midnight, they were taken to the central jail.... I did not oppose the Emergency, but Urs felt it was a devastating development."

Did H.D. Devegowda want to join the Congress? According to Krishna, he did. "During Emergency, Devegowda, who was on parole, had come to meet me secretly at my residence," says Krishna. "He arrived in an autorickshaw. He told me he was disappointed with the lack of unity and ethics in the opposition and wanted to join the Congress. I reminded him that he had just made 18 serious allegations against the incumbent chief minister (Urs).... And, if he jumped to the Congress now, he would put his own dignity at stake before the people. I suggested he instead tell the Congress that he was ready to join hands if Urs was removed from the post. Devegowda went silent for some time. He told me what I said had truth and he had been hasty."

Krishna says that the Congress party had several factions and it was not easy to hold them together. The surnames Kesri, Rao or Pawar would not work the way a Gandhi did. This was the reality, writes Krishna, on the circumstances that lead to P.V. Narasimha Rao's elevation to prime minister, though most of them wanted Sonia Gandhi to lead. "PVN was a good coordinator and consensus developer, but also indecisive. This created problems for both the party and the government. His best decision was to give finance minister Dr Manmohan Singh a free hand, which opened up the Indian economy," he says.

According to Krishna, in a private conversation between Manmohan Singh and his classmate Prof K. Venkatagiri Gowda, Singh had said that Krishna was doing commendable work as chief minister, and that if the UPA came to power in 2004, there was a possibility that either him or Krishna would be considered for prime ministership. The book mentions that Gowda had shared this matter among his close friends.

For making Bengaluru the startup capital of India, Krishna earned the nickname of "Bangalore CEO". But he also had many challenges as chief minister, like the Cauvery water row, drought and the abduction of Kannada actor Dr Rajkumar by brigand Veerappan. "I asked God why he chose to give me all the hardships," he reflects. "But now I know it is the challenges that a man faces that make him a leader."