It was a small Diwali party at a bachelor pad. There were about two dozen people in their mid-30s. The conversation, triggered by a weird break-up story, was mostly about the absurd experiences in relationships, during dates and otherwise. A girl mentioned how one of her Tinder dates passed out on her while they were making out and she “almost died under his weight”.

Just then, Ishita Bhatnagar Shetty, a 34-year-old working with a multiplex chain, recalled a movie where something similar happened. Even before she could name the film, someone asked: “Are you talking about Super Deluxe?”

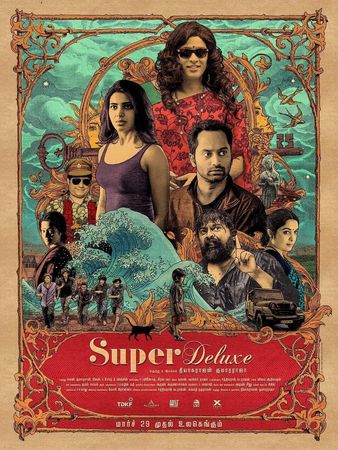

In one of the early scenes of the much-talked about 2019 Tamil film, directed by Thiagarajan Kumararaja, a man dies in the middle of sex. What follows is a series of quirky moments with a revelation that the woman was married to someone else. Starring Fahadh Faasil, Ramya Krishnan, Vijay Sethupathi (in a pathbreaking role of a transgender) and Samantha Akkineni, among others, Super Deluxe, in all its eccentricity, delighted audiences and critics alike.

Krishnan, who has been acting for almost three decades, plays an adult film actor in the movie. She conceded that Super Deluxe was not Baahubali, in which she plays Sivagami, and which had a lot of might put behind it for a wider reach. “I am glad so many people have noticed Super Deluxe because it is a lovely film,” she said. “I feel it is one of the best works of my career. We are talking about such films because people have started accepting such films and, more importantly, appreciating them. And so, filmmakers see an opportunity to narrate stories that are different.”

In that odd bunch at the party, which included people from different professions, there were hardly one or two who had not watched Super Deluxe. And they, too, said they would add it to their watch list on Netflix.

Super Deluxe was not the only non-Hindi film to grab eyeballs this year. Bornodi Bhotiai (directed by Anupam Kaushik Borah) and Aamis (Bhaskar Hazarika) from Assam created a similar wave. So did the Gujarati film Hellaro (Abhishek Shah), Kannada film Gantumoote (Roopa Rao) and the Malayalam movies Kumbalangi Nights (Madhu C. Narayanan), Jallikattu (Lijo Jose Pellissery) and Moothon (Geetu Mohandas).

None of these films had larger-than-life heroes, item numbers or publicity stunts. Nor were they shot in exotic locales. They were, instead, based in local lands and brought out real stories. They took you to places that you connected with and talked about issues that plague us socially, but in a way where storytelling took precedence.

For instance, Bornodi Bhotiai, a story largely about four friends and their love for one woman, puts forward the disappointments of each men in the big cities and their eventual return to their hometown Majuli, to start afresh. Aamis—brave and subversive—begins with the idea of forbidden love, but goes into an unexpected territory that revolves around the politics of food.

Gantumoote can broadly be categorised as a coming-of-age drama, but its victory is in the way it puts its female protagonist at the fore and shows us the world through the emotions she is going through, and the complexities that she is dealing with. Hellaro, which won the 2019 national award for best feature film, is based on folklore and is set in a remote Kutchi village in 1975. It could have been any other period film tracking the history of its place, but it turns into one about women discovering their freedom through song and dance. In the same manner, Kumbalangi Nights, a story of four brothers dealing with individual issues, has underplayed moments that address important social realities related to religion and patriarchy. Jallikattu, on the other hand, packs enough action and drama in a film where a buffalo takes centre-stage. It keeps its politics intact without being overt about it.

“People are getting tired of the one-kind cinema coming out of Mumbai,” said Bhaskar Hazarika. “And, also, digital has made it easy for people to discover new content. The films that are made in non-Hindi languages have got more visibility in the past couple of years.”

Hazarika got the idea for Aamis after he saw a couple eating at a food court. “It was the trigger for this whole chain of thought about notions of right and wrong, taboo and debauchery, love and lust, and the larger issue of a complete lack of empathy and understanding for those who have sinned,” he said.

For Abhishek Shah, a casting director-turned director in Gujarat, a bunch of true stories sparked Hellaro. Talking at Film Bazaar, south Asia’s biggest film market, in Goa, he recalled one of those. Once, when he asked a female friend why she did not put up her photos on social media, she said, “Ussey acha nahi lagta (he [husband] does not like it)”. Shah remembers thinking to himself, “How can someone take away your agency?”

And this led him to Hellaro, which is “a journey from suppression to expression” in a land where the rainfall is sparse. Besides becoming the first Gujarati film to win the national award, the film has had a long run in theatres, and not just in Gujarat.

“Isn’t it wonderful?” asked filmmaker Rima Das. “We are finally at a time where filmmaking and stories have taken precedence over regional barriers.”

Das, an independent filmmaker in the truest sense, has transcended geographical boundaries with her films Village Rockstars and Bulbul Can Sing. The films, which have been screened at national and international festivals, have been appreciated for their subtle storytelling and for bringing to light stories of domination and prejudice based on caste, religion and gender.

That could also be said of Geetu Mohandas’s films. Moothon, the second directorial feature of actor-turned director Mohandas, after Liar’s Dice, premiered at the Toronto International Film Festival this year. It got a standing ovation. She mentioned at the post-screening discussion that she has realised that her films have mostly been about searching. During an interview with her in October, I told her that her films are as much about the oppressed and the marginalised. “Well, we have to tell our stories, stories that inspire people, stories that brings the best out of people,” she said. “For me, I am drawn towards telling real stories of real people.” She recalled how, while filming in Kamathipura, the red-light district of Mumbai, for Moothon, she had thought the people and the environment there would be hostile. “But I was so wrong,” she said. “There were such great people. And, it was our responsibility that we do not disturb their lifestyle. So, we shot with as few resources as possible.”

More than any other language, it is Malayalam that is being talked about with great interest. So much so that at a public screening of the Malayalam film Virus in Mumbai this year, an audience member asked director Aashiq Abu what the people in Kerala were eating. “It is because of the so many young filmmakers that have emerged in the past few years,” said Mohandas. “They are very unapologetic in the way they want to tell their stories.” However, she does concede that the run-of-the-mill stuff still exists. “We still have a mixed bag. We still have the commercial blockbusters. We still have the huge business running [out of] the herd mentality where it is still star-driven to a certain extent, where the fans [of the stars] will dictate how the stars have to be positioned and what type of films will work for them. We want to do interesting cinema, but we are scared [thinking of] the box-office response. All those dilemmas are there, even in Malayalam. But there is also a section of new filmmakers that has emerged to tell real, content-driven stories.”

That makes all the difference. “I think if the content is good, people will watch it, irrespective of whether it is Bollywood, star-driven or regional,” said Hazarika. “But the innovation is happening more in the regional space because the stakes are lower.”

Lijo Jose Pellissery, however, does not believe in brackets. It upsets him. “Cinema is always cinema,” he said. “If it is good cinema, people will watch it, if it is bad, they will bitch about it. It is as simple as that. If you have made good cinema, it will find its audience at some point.”

However, he agreed that streaming platforms make access easier. “Prominence is given to subtitling, making it easier for people to understand,” he said.

Vijay Subramaniam, director and head, content, Amazon Prime Video, is humbled that creators are putting streaming platforms on a high pedestal. “Everything we do starts with our customers,” he said. “It is important for us to also acknowledge that the taste of the audience is never constant. It is important to understand that we are dealing with many Indias.”

What has also helped, said Das, is that the film festival culture has grown. “You see more youngsters flocking to the festivals and queuing up for films irrespective of the place,” she said. Her films have screened in festivals in Kerala, Kolkata, Delhi, Himachal Pradesh, Odisha and Mumbai. “It just leads to a word-of-mouth (promotion) when the locals watch it,” she said, adding that except for a few states like Bihar, Jharkhand and Haryana, where the festival culture is yet to pick up, people seem aware about films, which “leads to the growth of content-driven cinema”.

The filmmakers are also learning. At the time of his first release, Kothanodi (2015), Hazarika said his team was “very raw and did not know how to push a film with little understanding of the distribution system and how it works in India”. His latest film, however, was endorsed by director Anurag Kashyap. “To put a film in the public domain is really difficult because you need a big public relations budget,” he said. “It is not practical and almost an impossible task. To have a celebrity endorsement really helps.” So does every tweet, Facebook post or any social media interaction.

“We had a small release outside Assam and the response has been pretty good,” said Hazarika. “I have been following the feedback coming in on social media and even the live response during screenings has been really good. Perhaps we have been able to communicate what we wanted to communicate.”

Of course, people still like the star-driven, mega blockbusters, said Subramaniam. “But they also like the high-on-concept films,” he said. “When one talks about Kumbalangi Nights or Virus, these are hallmark stories that are being told. They are being told and consumed by the community that they are being told for, but at the same time, what streaming platforms like ours do is liberate [them from] the constraints of distribution.”

Siddharth Jain, director, Inox Group, a multiplex chain, told me that streaming platforms, contrary to popular belief, have added to the theatre-going audience because “now people wait for a certain film to release”.

“If you see box-office collections over the past five years, they have been growing every year even on a same store basis,” he said. “You have to understand that platforms like Netflix are a niche market of five to 10 lakh people. Overall, there are two billion cinema tickets sold in various strata of society across the country. But streaming has made people want to consume more content. Traditionally, we would consume content three hours a week. Now, we consume content three hours a day. In that sense, there has been an expansion of the market in itself. Nobody has eaten from each other. We are eating from our free time.”

And that awareness has led to a boom in content coming from different regions. “It is the fastest growing sector right now,” said Jain. “The educated audiences, and the audience who wants to go back to their roots have lapped up the new revolution in films. With quality of content on the rise, everyone is embracing it. The fact that Bollywood has taken a cue from regional films like Sairat (Dhadak) and Arjun Reddy (Kabir Singh) says a lot about the explosion that language films are bringing.”