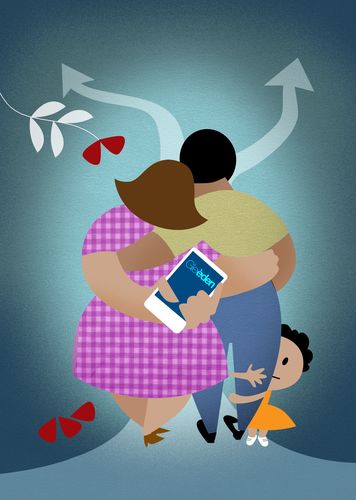

Sakshi had been married for eight years when she met Sundar on Gleeden, an extramarital dating website she joined two years ago. That was her first time on a dating app; she joined it because a friend advised her to. “Others were just interested in mauj-masti [fun and frolic],” says the Delhi-based techie who lucked out with Sundar after a series of dead-end conversations and encounters with other dates. After secretly courting him for four months, she filed for divorce. Sundar, too, broke free of the rut his marriage had become. He found a job in Delhi to be with his new partner. Today, Sakshi and Sundar are married and live in the same house with their children—Sakshi’s two children and Sundar’s three from their respective first marriages.

Sakshi makes it sound like a cakewalk, but the last two years had pushed her to the brink. She got on to Gleeden because it was free for women to register. Because she wanted to “cheat”. Because she knew that was her only way out. She had suffered enough beatings and emotional abuse at the hands of her ex-husband in the last five years. “When you take this step on your own, they start maligning your character,” says Sakshi, who grew up in a small town in Haryana before getting a job in Delhi. “That makes things a lot easier. There is no pretense about reaching an understanding. I had to do this for my children. Why should there be any guilt? My ex-husband gave me the perfect excuse. That arranged marriage was like a bad dream. I am happy I got a chance to end it on my terms.”

When the Ashley Madison scandal broke out in 2015, even India could not play the sanctimonious upholder of marital loyalty. Ashley Madison, the Canadian “married” dating online service—also called the infidelity website—was hacked, with 37 million accounts leaked. Most users were revealed to be men looking for extramarital relationships. India, apparently, had over 2.5 lakh accounts, with Delhi registering the highest number of users. A map based on leaked data showed that in India most users were women. It was widely believed that these accounts were not genuine as Ashley Madison was accused of generating fake female profiles to project a profusion of women on their website. But that was 2015. In less than four years since then, it is much harder to pigeonhole extramarital dating apps as enablers of infidelity or disloyalty. It is much too simplistic.

The French extramarital dating app Gleeden, run exclusively by women, entered India in 2017 and claims to have more than 4.5 lakh users in the country. Some 30 per cent users on the app are women. In September, the Supreme Court of India declared the law against adultery unconstitutional and recognised the sexual autonomy of women in marriages. Today, words like cheating, open, extramarital or polyamory demand deeper scrutiny and dissection, especially because adultery has existed since marriage was invented. What does an app like Gleeden really signify even though one can be married and go Tinder-happy? Does it really signal a shift in the way women are claiming their agency in extramarital affairs?

“People are more courageous and open. Courage here means accepting oneself. Previously, there was no effort to understand one’s needs and who one was as a person. The transition has been about what one wants to be,” says Priya, an avid traveller and trekker. She is always on the road, as she works in the tourism sector. She joined Gleeden about a year ago and has already dated some seven men. Priya has been happily married for seven years and has worked out the parameters of her loyalty with her husband. “Your wife might be the best friend in your life, but you might not be sexually attracted to her. Most men are unable to share their concerns with their wives. They just keep things bottled up and are too involved to playing their socially-sanctioned roles,” says Priya, who has dated men much younger to her and also men who are less than a year into their marriage.

And, the primary human need is to talk, explains Priya. “I am only trying to say that if somebody can give you that comfort of just being yourself, then you have to be on the lookout,” she says. “India is yet to accept the fact that people essentially look for companionship. And, these apps come as a saviour.” Priya is also on Tinder, but not too happy there for its lack of adequate filters when it comes to preferences and compatibility.

You can market an app as feminist, they say, but you cannot drill feminism in Indian men. Gleeden does not come cheap for men. They have to go through a more stringent verification procedure on Gleeden and shell out a minimum of Rs 1,600 to be able to send 15 messages.

Sunil Bhatia, 31, has not found a single match in the last two months. But, the management consultant in a Spanish company is hopeful. Sunil, married for seven years, does not get along with his father-in-law, who is a high-ranking police officer. The cop has barred his daughter from going back to Sunil. Until the time she returns, Sunil would like to meet women more amenable to brief sexual relations. “I also want to understand female psychology better to improve my marriage. I have never dated anyone before my wife,” says Sunil, who is not interested in single women as they tend to get “serious”. Married women, he says, know how to have fun.

(Names have been changed to protect identity.)