I was discussing the entire board with my brother judge, sorry,” said Justice Dhananjaya Y. Chandrachud as he arrived one day in his court some months ago. He was late by ten minutes. It is not usual for a Supreme Court judge to apologise or offer an explanation if he or she comes late to the court. But Chandrachud, whenever he is late, apologises.

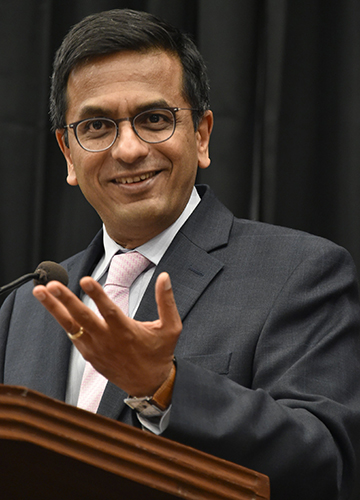

Chandrachud has endeared himself to a vast majority of court watchers with the manner in which he manages his court. His demeanour is said to be refreshingly different. If his humility is a rare quality in a person of his stature, he puts everyone at ease with his sense of humour.

Often at 4pm, he asks the lawyers in his court, “Don’t you feel the urge for a cup of tea?” Some time back, as the clock struck four, he elaborated on his love for tea and spoke about how he felt a strong craving for the beverage at that hour, which also happens to be the time for the court to wrap up for the day. He recalled that when he was a lawyer in the Bombay High Court, he would have his tea in the staff canteen which was next to a courtroom. When he became a judge, he sat in the same courtroom, and while he could smell tea being brewed in the canteen next door, he could not just enter the canteen anymore.

As chief justice of the Allahabad High Court, since the lawyers were more comfortable arguing in Hindi, he would help them shed their hesitation to switch from English to Hindi by starting off in his ‘Bambaiya Hindi’. Proceedings would commence in English, but would shift soon to Hindi and the lawyers appreciated the effort he took to make the situation more convenient for them.

He has also won admirers with his ability to differ from the established ways of working. Recently, he observed in his court with reference to providing the larger population with access to court proceedings: “Yesterday, I saw someone using a mobile phone, perhaps recording what we were saying during the proceedings. Initially, I thought, how can he record the proceedings? But then, my thought changed. What is the big deal? It is an open court hearing. Nothing is confidential here.”

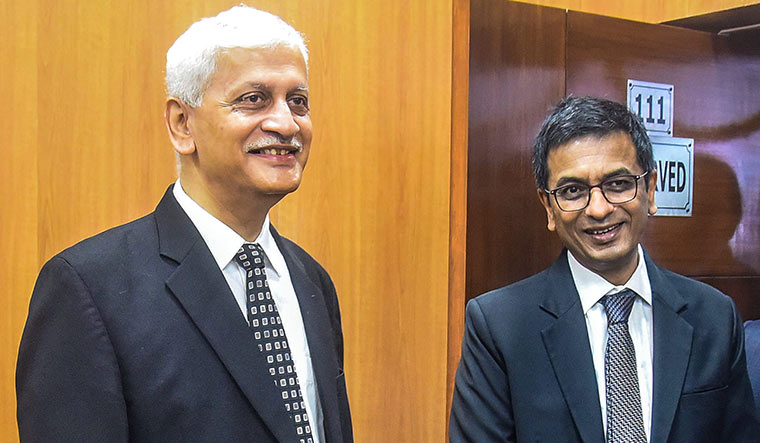

The 63-year-old Chandrachud, who takes over on November 9 as the 50th chief justice of India, enjoys a rockstar appeal in legal corridors and beyond. It is as much for his youthful smile and non-stuffy persona as for his ability to empathise with human suffering, give law a human face and his commitment to safeguarding free speech and individual liberty. He has often made refreshingly new interpretations of the law even if it has meant differing from his brother judges or even the judgments of his father, former chief justice of India Y.V. Chandrachud. He is known as the judge who is not afraid to dissent, speaks truth to power while possessing a brilliant legal mind that stays true to the basic tenets of the Constitution. His judgments are seen as not only being in step with the times, but also future-ready. That he is supremely articulate and has given many a quotable quote as a speaking judge has only added to his popularity.

However, Chandrachud almost did not turn to law and would have instead made a career in economics. The Bombay boy, who came to Delhi as a teenager when his father got elevated to the Supreme Court, studied economics honours at the prestigious St Stephen’s College. He was among a minority of students who took up Hindi as a subsidiary subject, something he has spoken about as having held him in good stead decades later when he became the chief justice of the Allahabad High Court.

Writing about his Delhi University days in an essay titled ‘A Tryst with Economics And Law’, part of a compilation, Delhi University–Celebrating 100 Glorious Years, which came out recently, Chandrachud recalls that after graduating at first position in first class from St Stephen’s, he had decided to pursue master’s in economics from the Delhi School of Economics. “Since classes were due to start in a few weeks, I began attending lectures at the Campus Law Centre (CLC). I was captivated by law and by the way it was taught by our teachers. They intertwined questions of policy and constitutional morality with the quest for liberty and freedom. A few lectures at CLC led me to make the career-altering choice of pursuing an LLB degree,” he writes.

The time spent at Delhi University also exposed the Maharashtrian boy to the culture, diversity and stories of persons from different walks of life while also helping him acquire colloquial Hindi. It was also the Emergency years, and Chandrachud describes the atmosphere at the university as hushed, but notes that despite the curbs, vibrant meetings and gatherings happened, which set the tone for a society founded on the core values of liberty and free speech. These ideals have been at the heart of Chandrachud’s most significant judgments.

Chandrachud did his master’s in law and also obtained a doctorate in judicial sciences at Harvard University. He began his career as an advocate practising in the Bombay High Court and the Supreme Court. He has often spoken about having fond memories of the times he spent in the Bombay High Court, first as a lawyer and then as a judge. He was among the youngest to be designated a senior advocate at the age of 39 in 1998. He also served as additional solicitor general of India from 1998 to 2000, until he was appointed as a judge of the Bombay High Court. In 2013, he was appointed chief justice of the Allahabad High Court and was elevated to the Supreme Court in 2016.

Chandrachud, who is commonly referred to as ‘DYC’, is especially popular with the younger set. Law students and interns come to his court to hear him. The feeling is mutual as Chandrachud is described by his peers and juniors as being young at heart and keen to learn new things, be it in the field of law or even books, movies and music from the experiences of his judicial clerks who come from varied backgrounds. He always accepts invitations to speak at events in law colleges, but the same cannot be said about other events.

The multi-faceted man loves to read and travel but desists from socialising as it eats into his ‘me time’. If his original favourites in music included Bob Dylan and ABBA, he has kept up to date by listening to Coldplay and later on ‘Despacito’ by Luis Fonsi.

Chandrachud’s family is originally from Pune; he was born and brought up in Mumbai. Both his parents were deeply immersed in Indian classical music. His father was trained in classical music, while his mother, Prabha, sang for the All India Radio. One of his prized possessions is an autograph from the legendary Kishori Amonkar. If music, besides law, formed the backdrop of his growing up years, there was also passion for cricket which he shared with his father. He was a big fan of Sunil Gavaskar and later Sachin Tendulkar, and his current favourite is Virat Kohli.

Senior advocate Ajit Bhasme, who grew up with Chandrachud in Mumbai and was two years his senior in school, remembers the judge as a good natured, sporty youngster who loved to play cricket in the building compound, his playmates including the likes of the children of film star Shashi Kapoor as also the kids from the servants’ quarters. “He is a hard worker. He has no vices except for his obsession with work,” said Bhasme. “He has the ability to build bridges and reach out to people who may not be in agreement with him. I am confident that as CJI he will be able to take along his judge colleagues and also reach out to the bar and resolve their issues.”

Chandrachud’s first wife, Rashmi, had died from cancer in 2007. Some years later, he married Kalpana Das, who was formerly working with the British Council. His elder son, Abhinav, practises law at the Bombay High Court and younger son, Chintan, is employed with a law firm in the UK.

Chandrachud, the judge with a vision for the future, is best understood when placed against the backdrop of the formidable legal legacy that he inherits from his father, who holds the record for the longest tenure as CJI―seven years. He has spoken about having imbibed from his father, whom he has described as his best friend, the importance of law having a human face. That said, it is also in having differed with his father’s judgments that he has established himself as a judge who is not afraid to offer a different opinion.

It is learnt that a fellow judge had even cautioned Chandrachud as he went on to overrule his father’s judgement with regard to adultery in 2018, saying that it was a well reasoned verdict. However, Chandrachud was convinced that it was erroneous. He was part of a five-judge Constitution bench that unanimously struck down Section 497 of the Indian Penal Code as unconstitutional, thus decriminalising adultery.

In 2017, while writing his separate yet concurring order in the apex court’s judgment that declared that privacy was a fundamental right, Chandrachud had overruled a verdict passed by a five-judge Constitution bench in 1976―that included his father―in the ADM Jabalpur case. The court had against the backdrop of the Emergency by a majority of 4:1 upheld a presidential order that barred anyone detained or arrested from seeking relief through a habeas corpus or any other writ filed in the high court. Overruling the ADM Jabalpur verdict, Chandrachud wrote, “The judgments rendered by all the four judges constituting the majority in ADM Jabalpur are seriously flawed. Life and personal liberty are inalienable to human existence.”

As Chandrachud takes over as CJI for a relatively long tenure of two years, there is great anticipation over the impact he will have on the functioning of the Supreme Court as also the judiciary as a whole. This has got a lot to do with the judgments passed by him during his stint as a judge in the apex court that began in 2016. His verdicts, whether dissenting or concurring, have been viewed with great interest. They have been described as progressive, upholding the rights of the individual and viewing those on the fringes of society or those who are in a disadvantaged situation with compassion and empathy.

Senior advocate and former additional solicitor general Bishwajit Bhattacharyya said the task before Chandrachud was enormous and he would have to rise to the occasion to meet the expectations. “I am absolutely sure that he will give a new direction to the judiciary. He will primarily have to live up to the expectations of the litigants. The judiciary exists for the litigants,” he said.

Be it his judgment on privacy, that was viewed as having paved the way for the landmark verdict that decriminalised homosexuality, or his dissent in the Aadhaar case, where he said that the scheme reduced a person to a 12-digit number, or in the Bhima-Koregaon matter, where he said “dissent is a symbol of a vibrant democracy”, or the Sabarimala case, where lending his weight to the majority verdict he said excluding women from worship was to place them in a position of subordination, or more recently, in the abortion case, in which he said women who conceive out of marital rape could seek termination of pregnancy within the specified period, Chandrachud has come to be known as a judge with a progressive view of justice.

If the liberals have found a hero in Chandrachud, the verdict in the Ram Janmabhoomi case, where it was widely speculated that he had authored the judgment, is among a clutch of decisions that has been welcomed by the other side of the divide.

It is clear that Chandrachud has generated great interest in the last six years as a Supreme Court judge and there is already immense anticipation with regard to his tenure as CJI as also great expectations. He has to deal with the two perennial issues of pendency of cases and vacancies in judicial positions.

“Ending the adjournment culture and ensuring increased supervision over lower judiciary, given that 99 per cent of pending cases are in the high courts and subordinate courts, have to be among the foremost priorities of Justice Chandrachud,” said Abhinay Sharma, managing partner, ASL Partners. Sharma said Justice Chandrachud would also have to ensure a smooth working relationship with the executive in terms of fast-tracking appointment of judges.

According to Pratyush Miglani, managing partner of Miglani Varma & Co, Chandrachud’s openness towards broadcasting constitutional bench hearings sets the expectation that the court’s functioning will become more and more transparent. “We have seen him bat for the need for law to keep up with technological progress, and for judicial institutions to shed inhibitions about using technology. That leaves us with tremendous hope that the court will adopt newer technology to improve access to justice for the masses, setting an example for courts below, including the high courts and district courts,” Miglani said.

Chandrachud as head of the Supreme Court’s e-committee has been credited with putting in place a system that worked well during Covid-19 by ensuring the courts turned to the virtual mode. “Justice Chandrachud’s emphasis on finding technological solutions for the court’s problems is heartening. He has the will to bring about the necessary changes and is on course to making the court a paperless place,” said Pradeep Rai, senior advocate and vice president of the Supreme Court Bar Association.

Sneha Kalita, advocate-on-record in the Supreme Court, said Chandrachud’s humane approach to running the court sets him apart. “He has a friendly approach, is accommodating and takes it upon himself to encourage young lawyers who appear in his court,” she said.

Amidst the intense discussion over Chandrachud becoming the new CJI, former judge of the Delhi High Court Justice R.S. Sodhi said: “He has a daunting task ahead of him and I expect him to be ready with a plan to deal with the various issues that plague the judiciary. Cutting through the hype, he has to focus on his job as the administrative head of the judiciary.”

Chandrachud had once said, “It is well for a judge to remind himself or herself that flattery is often the graveyard of the gullible.” The biggest challenge for him will be to live up to the expectations.

Judge of character

▸ Justice Chandrachud practised law at the Bombay High Court and the Supreme Court

▸ Designated senior advocate, at 39, by the Bombay High Court in June 1998

▸ Additional solicitor general of India: 1998 until appointment as a judge

▸ Judge of the Bombay High Court: March 29, 2000, until appointment as chief justice of the Allahabad High Court

▸ Director of Maharashtra Judicial Academy

▸ Chief justice of the Allahabad High Court from October 31, 2013, until appointment to the Supreme Court on May 13, 2016

Quote unquote

▸ “We will not adjourn the matter. We don’t want the Supreme Court to be ‘tareekh pe tareekh’ court. We want to change this perception.”

▸ “It is well for a judge to remind himself that flattery is often the graveyard of the gullible.”

▸ “History and contemporary events across the world are a reminder that blackouts of information are used as a willing ally to totalitarian excesses of power. They have no place in a democracy.”

▸ “The essence of judging is compassion. You take out compassion from judging, and you will be left with only the husk.”

Notable judgments:

▸ Right to Privacy: “Privacy is a constitutionally protected right, which emerges primarily from the guarantee of life and personal liberty in Article 21 of the Constitution.”

▸ Euthanasia: “…To deprive an individual of dignity towards the end of life is to deprive the individual of a meaningful existence.”

▸ Decriminalisation of adultery: “Ostensibly, society has two sets of standards of morality for judging sexual behaviour. One set for its female members and another for males.”

▸ Entry of women in Sabarimala: “To exclude women from worship by allowing the right to worship to men is to place women in a position of subordination. The Constitution should not become an instrument for the perpetuation of patriarchy.”

▸ Gender parity in armed forces: “Women officers of the Indian Army have brought laurels to the force... Their track record of service to the nation is beyond reproach. To cast aspersion on their abilities on the ground of gender is an affront not only to their dignity as women but also to the dignity of the members of the Indian Army.”

Batting for rights

Aadhaar:

▸ “The entire Aadhaar programme, since 2009, suffers from constitutional infirmities and violations of fundamental rights. The enactment of the Aadhaar Act does not save the project. The Aadhaar Act, the rules and regulations framed under it, and the framework prior to the enactment of the Act, are unconstitutional.”

Bhima-Koregaon:

▸ “Circumstances have been drawn to our notice to cast a cloud on whether the Maharashtra police has in the present case acted as fair and impartial investigating agency...Sufficient material has been placed before the Court bearing on the need to have an independent investigation.”

Abortion:

▸ “All women, whether married or in consensual relationships, including persons other than cis-gender women, are entitled to seek an abortion within 20-24 weeks of pregnancy. Also, women who conceive out of marital rape can seek termination of pregnancy within the specified period.”