IT WAS A ‘YOGA CLASS’ at Narath in Kerala’s Kannur district that marked the beginning of the end of the Popular Front of India.

On April 23, 2013, the Kerala Police got a tip-off that PFI activists were using a building under construction in the town to conduct weapons training disguised as a yoga class. As the police raided the building, the two lookouts at the gates fled. Inside, the police found a jute sack spread over a table. On top of it were iron nails, pieces of glass, ash-coloured powder, a bundle of thread, and two live bombs.

A thorough search of the site unearthed an iron sword, a petrol-soaked brick in a bucket fastened by metal wire, a wooden target shaped like a man, and five long wooden sticks. Also seized were raw material for making improvised explosive devices—aluminium powder, potassium chlorate and sulphur. The two live bombs were quickly defused.

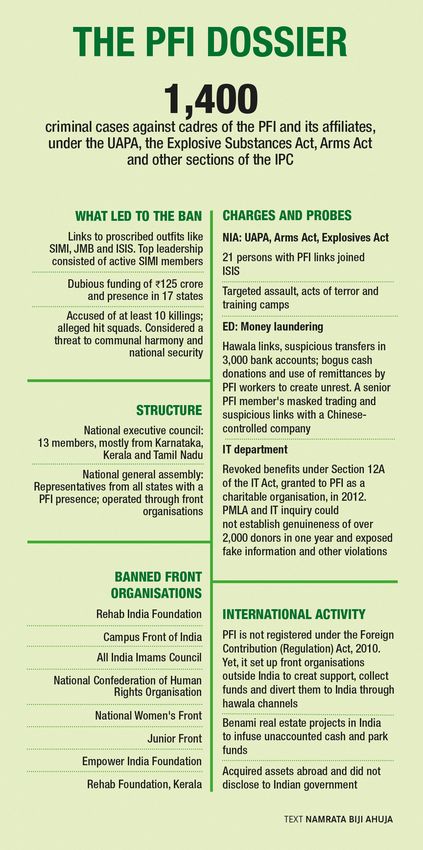

The building belonged to the president of the PFI in Kannur. Arrests were made and a first information report under the Arms Act, the Explosive Substances Act and the Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Act was registered. The National Investigation Agency soon took over the probe. On August 7, the NIA in Kochi re-registered the case, charging 24 people for “organising a terrorist camp, training youth in the use of explosives and weapons, and endangering the unity and integrity of the nation”. The accused included leaders of the PFI and its political offshoot, the Social Democratic Party of India.

Narath turned out to be the first nail in the PFI’s coffin. The last one was struck by security agencies a few days ago. In what was the biggest coordinated anti-terror crackdown, the NIA oversaw two rounds of raids against the PFI that began on September 23. More than 100 properties across 15 states were raided, and around 250 people were arrested. Subsequent protests by PFI activists turned violent, with PFI strongholds in Kerala and Karnataka witnessing arson, violence and destruction of public property. The Union government finally banned the PFI and several of its affiliate organisations on September 28, for carrying out unlawful activities “prejudicial to the integrity, sovereignty and security of the country”.

For years, the PFI had occupied the top of the pyramid of radical Muslim organisations in India. The ban on it has therefore found widespread support. Major political parties have either voiced approval or given silent support. Mainstream Muslim organisations that had for long opposed the PFI’s politics—such as the Indian Union Muslim League and the Jamaat-e-Islami—have publicly backed the ban.

The roots of the crackdown on the PFI precede Narath. Investigating agencies did a decade of spadework using human, cyber and technical intelligence. Piles of evidence—related to the PFI’s holding of terror training camps and laundering black money to its establishing links with Islamic State and Al Qaeda—were gathered by the NIA, the ED and the Intelligence Bureau and submitted to Union Home Minister Amit Shah.

As the agencies found out, the IS threat was closer home than imagined. With the deadly lone-wolf attacks in Rajasthan and Maharashtra a few months ago, intelligence agencies had anticipated a surge in IS and Al Qaeda modules in the Persian Gulf and Turkey, where the PFI runs a lucrative, well-oiled machinery that feeds extremism and promotes the common agenda of spreading Islamic rule. An NIA dossier said the PFI had formed “hit squads” to carry out “revenge attacks” on RSS leaders and Hindu activists.

The PFI is alleged to have been behind several brutal killings in the past few years. Cases against PFI activists have been registered across the country—from Darbhanga in Bihar to Shivamogga in Karnataka and Kochi in Kerala. The NIA probe into the 2020 Bengaluru riots revealed the involvement of SDPI office-bearers.

Security agencies began completing the jigsaw puzzle of terror charges against the PFI in 2021, when a special task force of the Uttar Pradesh Police arrested Rauf Shareef, national general secretary of the Campus Front of India, the PFI’s student wing. Shareef, who had earlier been arrested by the ED in a money laundering case, was charged with trying to incite communal violence in Hathras district.

Investigators discovered that he also had links with Mohammed Shafeeque Dar Rahima, a Kannur native who collected slush funds for the PFI from abroad. Around the same time, explosives and extremist literature were recovered from the Padam forest area in Kollam district, a known PFI training site. The same year, Anshad Badruddin, national coordinator of the PFI’s physical education division, was caught carrying explosives and detonators.

In February this year, the ED mapped the money flow and sent an exhaustive note to the NIA. It had details of illegal funds collected by the PFI’s “district executive committees” in the UAE, Oman, Qatar, Kuwait, Bahrain and Saudi Arabia. The activities of Ilyas Sayed Mohammed, a Malayali who was president of the PFI’s district executive committee in Riyadh, was cited as an example. In India, as many as 3,000 bank accounts belonging to 27 PFI members and 45 associates in 10 states were analysed to map the money flow.

Pervez Ahmed, president of the PFI’s Delhi unit since 2018, was soon arrested. He told investigators that the PFI did not issue receipts at the time of receiving donations. The practice, apparently, was to collect all contributions and transfer the amount to PFI district offices, where unit presidents would “issue” receipts. The trail of bogus donations and bank transfers has been corroborated by statements recorded by arrested PFI members. Also, many ‘donors’ have denied giving money to the PFI; many of them have even said that they did not have the wherewithal to make the kind of hefty donations that the PFI says they did. “These contributors were poorest of the poor who had no idea about the money flow,” said an investigator. “Their accounts had been opened at the behest of PFI, and the accounts were being used without their knowledge.”

While the ban on the PFI and its affiliates will have an immediate impact on the national security front, it is unlikely to resolve political challenges soon. The SDPI, a political offshoot of the PFI that carefully projected a secular outlook, has been growing in Kerala. In the 2010 local body polls, it had won just 11 seats. Currently, it has 103 members in local bodies across the state.

In Karnataka, too, the SDPI has been mining political support amid the continuing polarisation on caste and communal lines, especially in the state’s coastal regions. There are also fears that the ban on the PFI would only result in the emergence of a more sophisticated militant outfit.

For now, though, the focus of the security agencies is to gather as much evidence as possible to put the PFI’s main leaders behind bars. “With the arrest of the top leadership and the freezing of bank accounts,” said an investigator, “the outfit is expected to suffer a setback that takes it back almost a decade.”

With V.V. Binu