Just over a month before Vladimir Putin’s troops invaded Ukraine, the German navy chief, vice admiral Kay-Achim Schönbach, was in India for a brief visit. Delivering a lecture at the Manohar Parrikar Institute for Defence Studies and Analyses in Delhi on January 21, Schönbach said Putin would never invade Ukraine. What Putin really wanted, he argued, was respect. “It is easy to give him the respect he demands, and probably deserves,” said Schönbach. The lecture caused a major furore in Berlin, not on account of its contents, but because the admiral allowed it to be placed on record. Two days later, he was forced to resign.

While Schönbach lost his job for airing his views, it offered a rare glimpse into the minds of the normally taciturn Germans. To be fair to the admiral, till the moment Russian troops moved into Ukraine, the entire German leadership, including Chancellor Olaf Scholz, probably shared his assessment.

In fact, Scholz, who belongs to the traditionally pro-Russian wing of the Social Democratic Party (SPD), was in Moscow on February 15, hoping to find a solution to the crisis. After the formal discussions, Putin, who speaks fluent German, invited Scholz for a drink, and a word in private. Scholz later told his aides that he was sure that Putin was not going to war. Less than a week later, however, Putin ordered his troops into Ukraine. For Scholz, and for the entire German establishment, it came as a personal as well as political blow.

The manner in which Putin played Scholz, who was just two months into his new job as chancellor, may or may not have played a role in the German response to the invasion. The German retaliation has been unprecedented, and could be considered a watershed moment in the nation’s history. Shedding its initial reluctance, Germany completely reordered its strategic doctrines and joined other key European powers against Russia.

Scholz does not enjoy the reputation of being an inspiring speaker. His robotic monologues, closely resembling the style preferred by his predecessor, Angela Merkel, often put listeners to sleep. Yet, on February 27, when he addressed an emergency parliament session, the normally staid lawmakers stood up several times to applaud him. “February 24 marked a turning point in the history of our continent,” said Scholz. “Putin doesn’t just want to eradicate a country from the world map. He is destroying the European security structure and it is our duty to protect Ukraine.”

With a single speech, Scholz signalled a “180-degree turn” of Germany’s post-World War II strategic and security policies. He announced that Germany would henceforth spend more than 2 per cent of its GDP on defence and that the provision would be written into the country’s constitution. He also announced a special €100 billion package to upgrade the German army.

Germany also gave up its decades-old history of not sending arms to conflict zones. A few weeks ago, it had stopped Estonia and the Netherlands from transferring German-made weapons to Ukraine. That ban has been lifted. Germany, too, has stepped up its military commitments. From offering Ukraine 5,000 helmets—a move which led to much criticism; Kiev Mayor Vitali Klitschko ridiculed that the next German consignment would likely be pillows—it is now sending 1,000 anti-tank weapons, 500 Stinger surface-to-air missiles and 2,700 Strela anti-aircraft missiles.

“Ironically, Putin has done more to unite Europe and the west than anyone else. The Russian invasion of Ukraine is the most critical security challenge facing Europe since World War II. It has woken up the German government to break with its traditional cautious position,” said Harry Nedelcu, policy director at Rasmussen Global.

Scholz basically dismantled the foundations of German pacifism, which was a compulsion and a commitment because of the atrocities Germany committed in the two World Wars and also the Holocaust ordered by Hitler. It also marked the end of its special relationship with Russia, nurtured carefully by the German leadership because of the number of Russians who were killed by German troops in the Second World War.

In more pragmatic terms, it was also because during the days of the Cold War, West Germany was in the direct line of Russian fire. From the late 1960s, under SPD chancellor Willy Brandt, West Germany pursued “Ostpolitik (eastern policy)”, which was an attempt to cultivate friendly ties with the Soviet Union, especially through growing interlinkages in trade, commerce and energy.

After the collapse of the Soviet Union, a unified Germany largely followed the same template, till Scholz sought to make a U-turn. However, it was not just the invasion that forced the German hand. US president Joe Biden, a staunch proponent of the trans-Altantic alliance, has been putting tremendous pressure on Germany to dial down its burgeoning ties with Russia. Ironically, Biden’s predecessor Donald Trump, too, seems to have played a role in this policy shift as he had repeatedly berated Germany’s defence posture and spending, calling it a freeloader living off American largesse.

Scholz has also been helped by the unprecedented unity in Germany over Ukraine. Both his coalition partners—the Free Democratic Party led by Finance Minister Christian Lindner and the Greens led by Foreign Minister Annalena Baerbock—have closed ranks behind the chancellor. Even the opposition Christian Democratic Union and the far right Alternative for Germany support the shift. Their decisions are certainly informed by the fact that nearly 80 per cent of Germans now support a hawkish policy towards Russia.

Hundreds of thousands marched in Berlin on February 27, endorsing the decision to export lethal weapons to Ukraine and to rearm Germany. The formidable German military industrial complex will also be happy about the decision. Although its military is chronically undermanned and underequipped (it has less than two lakh soldiers, just about 300 battle tanks, 230 warplanes and 60 ships), Germany is the world’s fourth largest exporter of arms.

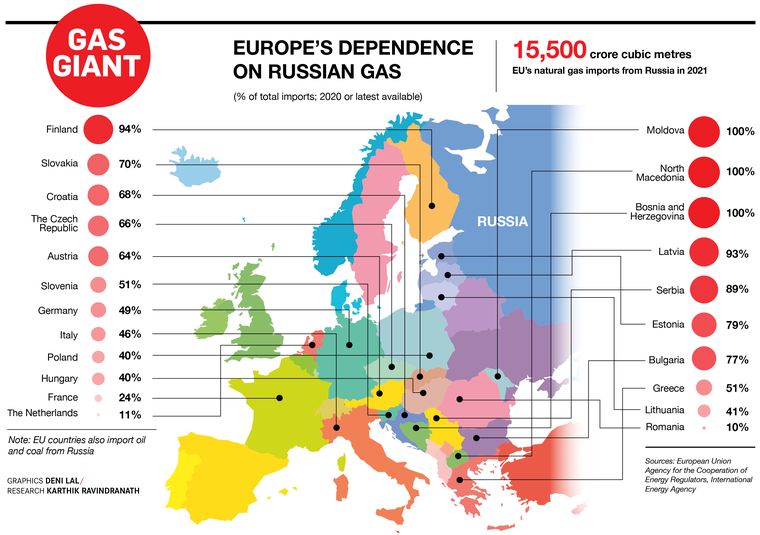

On the economic front, Scholz dropped German objections to cut Russia off from the SWIFT transactions system and joined the European Union in imposing a wide array of sanctions. An even bigger decision was the cancellation of the $11 billion Nord Stream II pipeline. Considering Germany’s dependence on Russian energy, the move to decertify the undersea pipeline which was built to carry Russian gas directly to Germany, was critical.

Germany imports nearly 60 per cent of its gas, 50 per cent of coal (especially hard coal used in industries like steelmaking) and 30 per cent of oil from Russia. While federal law stipulates that strategic oil reserves must last for at least 90 days, in the case of coal and gas, there is no such requirement. German companies, therefore, failed to take action when Russia systematically reduced its gas supply over the past few months in an apparent bid to put pressure on Germany. Most of the major gas storage facilities in Germany are now empty, operating under 10 per cent of their capacities.

As of now, Germany can import enough gas from Russia through the existing arrangements even without Nord Stream II. But the German government is thinking about diversifying its sources. Moreover, Putin could decide on weaponising energy and choose to punish Germany for its stand on Ukraine. As a result, Germany is considering several drastic measures, including delaying its nuclear and coal phase-out. After the Fukushima disaster in 2011, Germany had decided to shut down its nuclear plants—only three are left now—by the end of this year. And coal will be phased out by 2030 so that Germany can reach its climate change goals. A conflict with Russia could force Germany to revisit those goals and keep the plants running.

If Russia closes down its energy supply, it could hurt German industries, too, leading to an economic meltdown. David Folkerts-Landau, the chief economist at Deutsche Bank AG, said such a scenario would result in “a very serious recession”. Considering the gravity of the situation, Germany is trying to augment energy imports from the Middle East and is also eyeing liquefied natural gas (LNG) from the US. To receive the American LNG, the government has ordered the construction of two terminals on the North Sea coast.

Importing more oil and LNG would go against Germany’s stated climate change policies. American LNG is considered to be “dirty”, as it is produced by fracking, considered to be harmful to the environment. German climate activists in the past have been opposed to LNG, which is also more expensive than Russian gas.

Yet, many observers see a positive side to this predicament. “Putin may have indirectly reignited the conversation in Germany and also in the EU about switching to more renewable energy,” said Nedelcu. “The question over our dependency on Russia is reigniting the green conversation.”

The German leadership has finally agreed that instead of building gas reserves, the long-term solution is to expand renewable energy sources at a faster pace. The renewable sources, however, need critical minerals such as graphite, manganese, lithium, nickel and cobalt, and Germany is dependent on China for most of those, adding yet another dimension to the crisis.

A third key element that will determine the contours of Germany’s declaration of strategic independence will be its policy towards the Indo-Pacific, where India is also a major stakeholder. As Russian forces moved into Ukraine, key Indo-Pacific countries were worried that the US, which is the prime mover behind the concept, would divert its attention back to Europe.

The US has deprioritised Asia-Pacific several times in the past as it had urgent business to address elsewhere, such as in the Middle East and in Afghanistan. The US has, nevertheless, declared that it will keep its focus on the Indo-Pacific, despite the crisis in Europe. “It’s difficult. It’s expensive. But it is also essential. We are entering a period where that will be demanded of the United States,” said Kurt Campbell, coordinator for Indo-Pacific Affairs on the US National Security Council at an event organised by the German Marshall Fund of the United States.

Despite Washington’s optimism, the west, at the moment, does not have the capability to deal with a belligerent Russia and a rising China, simultaneously. The German rearmament could, however, alter this scenario, said Uma Purushothaman, who teaches international relations at the Central University of Kerala. “Germany paying for its own defence frees up the US to focus on the Indo-Pacific.”

As of now, the German interest in the Indo-Pacific is largely trade-oriented. But as the ongoing war in Europe has shown the Germans the limits of economic interdependence, Berlin could start looking at the Indo-Pacific and an increasingly bellicose China through the prism of strategic balancing. “Germany is watching very closely how China reacts to Putin’s war, but I don’t see a change of strategy right now. But, there is an awareness in Berlin that the change in relationship that just happened with Russia could happen with China tomorrow, if, for example, it invades Taiwan,” said Teresa Eder, who is with the Global Europe Program at the Wilson Center, Washington, DC.

While Germany has made the most significant and dramatic moves against Russia, the whole of Europe has come together in opposing Putin. The EU, which usually takes decades to arrive at important decisions, quickly set up a $500 million fund to arrange weapons for Ukraine, a first in the group’s history. Neutral players like Sweden and Switzerland, which refused to take sides even during both World Wars and the Cold War, too, have joined the anti-Russia front.

Switzerland’s decision to join the EU sanctions could affect Russian assets worth more than $11 billion in Swiss banks. Switzerland also banned five oligarchs close to Putin and closed its airspace to Russian flights.

Sweden has indicated that it would consider joining NATO, and is sending 5,000 anti-tank weapons to Ukraine, a first in 73 years. For the first time in history, a majority of Swedes want to join NATO.

In neighbouring Finland, too, a clear majority supports being part of the trans-Atlantic alliance. Finland has given Ukraine 2,500 assault rifles, 1.5 lakh cartridges and 1,500 anti-tank weapons. Finnish President Sauli Niinisto was in Washington, DC, on March 4, where he and Biden discussed further security cooperation.

“The accession of Finland and Sweden into NATO, which is first and foremost a military alliance, would have serious military-political repercussions that would demand a response from Russia,” said Russian foreign ministry spokesperson Maria Zakharova. Both Finland and Sweden dismissed the Russian charges and indicated that they were on a gradual path to NATO membership.

Putin’s unprecedented aggression has brought Europe together and it could potentially reshape the post-Cold War security architecture. Although Germany has become the engine of this unexpected churn, it remains to be seen whether it manages to stay the course.

Given Germany’s aggressive past and its present position as the predominant European power in terms of population, economic might and technological edge, the remilitarisation could be a touchy subject for the continent in the long run.

Russia, meanwhile, could make the cost of the policy change prohibitively high for Germany. “There will be a lot of internal debate and pressure to reconsider some of these policy shifts,” said Eder. “It is still ingrained in German minds that they don’t want to be militarily engaged, for historic reasons. This does not change overnight and just because the chancellor announced the end of an era.”