MALUKARAM WAS born to a Pakistani father and an Indian mother. He grew up in Rahim Yar Khan district of Pakistan’s Punjab province. His early memories there are of being labelled a Hindu, roaming the playground during Quran class in his school, not being allowed to enter madrasas and finally being told not to attend school in 1992 because Hindu boys were getting beaten up in colleges after the demolition of the Babri Masjid in Ayodhya. Carrying some pots and pans, Malukaram and his mother entered India in 1998.

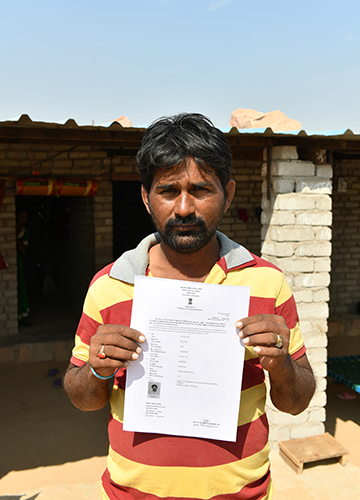

In 2005, he received a certificate that declared him an “Indian citizen”. It is kept in his one-room thatched house in Bheel Basti in Jodhpur, Rajasthan. Malukaram explains his conundrum. “In Pakistan, they called us Hindus. Over here, they call us Pakistanis,” he said. “When we die, our children will not be called Pakistanis and the generations that follow will be Indians; the new Indians.”

Malukaram’s two children study in Shri Saraswati Bal Veena Bharti School in Jodhpur. “I pay fees for one child and the other studies for free,” he said. “I earn around Rs500 by cutting stone and my wife does some embroidery and tailoring. We are a small happy family.”

His wife, Nanu, can read and write Urdu, a language she studied till Class 8 in Pakistan. But after she and her father, a retired fire brigade officer, fled to India two years later, she could not complete her studies. “I have no regrets,” said Nanu. “We make some money to educate our kids and they are doing very well in class. They have won so many medals.” She proudly displays the medals neatly arranged with her utensils.

Malukaram has been busy visiting New Delhi, taking part in delegation visits to senior cabinet ministers in the Narendra Modi government to raise concerns about citizenship issues, refugee rights and monetary assistance. But he is aware that the road ahead is long and tiresome.

Malukaram is unfazed by the nationwide protests against the Citizenship (Amendment) Act (CAA), 2019, and the proposed National Register of Indian Citizens (NRIC). For thousands of Hindu migrants like him coming from Pakistan, patriotism is not merely defined by citizenship laws, census enumeration exercises or geographical boundaries.

The non-citizen Hindu migrant population in the country is estimated to be around two lakh. Around 30,000 are residing in Jodhpur, Barmer and Jaisalmer districts of Rajasthan. Some lucky ones like Malukaram have got citizenship certificates. But even after getting citizenship, these migrants are in dire need of rehabilitation, including health care, education and housing facilities. People like Malukaram hold the certificates and breathe fresh air, but have little to fill their stomachs with.

“The citizenship certificate gives us an identity. But if we are not given all the rights enjoyed by an Indian citizen, then it is a mere piece of paper,” said Paru Ram, 35, from Sindh, Pakistan. Ram said he paid Rs12,000 to an agent in Pakistan for a pilgrimage visa, using which he crossed over into Indian territory in June 2019 with ten others. But he has no Aadhaar card to send his children to a regular school or to apply for a job or avail the benefits of government welfare schemes.

During the state elections in West Bengal, Kerala and Assam, where there is a sizeable population of minority communities, the CAA once again became a highly emotive issue. The BJP in its Bengal manifesto has already promised to implement the CAA in the first cabinet meeting if voted to power. Home Minister Amit Shah is fast peddling its implementation, saying the government has set July 9 as the deadline to frame the rules for the law. The home ministry has begun drafting rules to implement the amended law.

At an election rally in February in West Bengal, Shah said the CAA would be implemented once the Covid-19 vaccination programme is completed. He asked Muslims not to get misled by the claims of the opposition on the CAA. “It will not take away anyone’s citizenship. It is only for people who have been living here for years without any respect for no fault of theirs,” he said. But the political slugfest over what defines citizenship has begun.

Leaders like West Bengal Chief Minister Mamata Banerjee, Kerala Chief Minister Pinarayi Vijayan and Congress’s Rahul Gandhi are reiterating their opposition to the CAA. Those who are against the CAA feel the government should not discriminate on the basis of religion. Others fear that illegal migrants from Muslim-majority countries will turn into legal citizens.

With both—the implementation of the CAA and the plan to update the National Population Register with the 2021 census—once again on top of the Union home ministry’s agenda, the pot is likely to boil in days to come.

On the ground, the situation is taking the shape of a humanitarian crisis. There are lakhs of Malukarams and Paru Rams who want the same benefits of other Indians. What is more alarming are the long queues on the borders to acquire Indian citizenship. They are hoping the government and other parties look beyond politics and start talking about the problems engulfing the migrant population.

At the moment, Ram is not excited about the CAA finally being implemented, but he is more worried about meeting the elusive spy who comes to check on him often. Ram will be given a citizenship certificate only after his background has been thoroughly checked by the local Intelligence Bureau (IB) sleuth.

“When I entered India, I had a valid visa document and reported to the foreign regional registration office (FRRO),” said Ram. “But living in the basti is difficult since there is no work here. So, I mostly work in the fields on the outskirts of the city.”

When Ram and other men were in the fields far away, and each time the IB or the CID sleuths came to corroborate their identity, they were found missing from the village.

The intelligence agencies raise a red flag every time a Hindu migrant from Pakistan disappears from the border areas. This is because Pakistan’s ISI has been spying on the borders of Rajasthan, Gujarat and Punjab. It is an old practice of the notorious spy agency to disguise its spies as Hindu migrants and push them into Indian territory, legally or illegally, where they sometimes live on for decades.

Intelligence officials in New Delhi said the ISI would try to take advantage of the new citizenship law. This makes the job of the FRRO and the home ministry critical. It also becomes equally challenging for local police authorities and state administrations, which are responsible for sifting through thousands of citizenship applications landing in its office every month.

Nootan Das, 41, got Indian citizenship in September 2019 but he does not know if he should feel elated because his two daughters are still Pakistani citizens. “I have heard about the new law but I cannot afford to pursue the citizenship issue of my daughters anymore,” he said. “We need a roof over our heads and some money to run my shop. How can I worry about anything else right now?

Similarly, Pradeep Kumar, 33, said that his family had spent two decades and more than Rs40,000 in getting citizenship. Pradeep was 12 when he came to India. “Today, nine people in my family have got Indian citizenship,” he said. “If special camps are made where we can share our documents and if we are provided ration cards and voter identity cards once our nationality is confirmed, it will help us rebuild our lives faster. Had I got Indian nationality in 2005, when I was younger, I could have got a government job.”

With the fresh CAA announcement, there is a visible flurry of activity in the border areas once again. Luna Ram and his wife entered Indian territory in early 2020 along with several other families. They came on foot with valid documents. Squatting on empty plots, they have made temporary arrangements to cook with firewood, sleep on stone beds and ensure that their utensils and clothes do not float away when heavy rains come.

But these families are not complaining. They feel they have bid goodbye to bigger problems since setting foot on Indian soil. “We can sleep peacefully here,” said Govind Bhil. “It was difficult to take care of our daughters and sisters in Pakistan. Our boys were being taken away to work in the fields and converted on the pretext of making good money. The girls, especially the good-looking ones, were forced to marry Muslim men.”

Hindu Singh Sodha, a renowned activist for the cause of Pakistani refugees, said religious atrocities are the main reasons for Hindu families fleeing Pakistan even today. He pointed out that the minority protection bill could not be passed in Pakistan as it has been opposed by religious forces. “Though the Hindu Marriage Act is in place, it is redundant when it comes to protecting the rights of Hindus,” said Sodha.

Miles away in New Delhi, new rules for giving citizenship to persecuted Hindu migrants are being written. “Small steps make all the difference,” said a government official. “After years of neglect, we are trying to address the issue. A rehabilitation policy is also in the works.”

There is a light at the end of the tunnel. When the day breaks in these bastis of Hindu migrants, the sound of Swachh Bharat Abhiyan vans wakes up the new citizens and non-citizens, who line up to dump their garbage. These vans are a reminder that the wheel of time has turned.

Not far from the border, the national anthem is being played every day and children of Pakistani migrants rise up to sing it along with other patriotic songs. This is how a normal day begins at the famous Bheel Basti “Pak” Vista School.

“I love going to school,” said Sagar, 14, after performing Saraswati puja at the school assembly. “It takes me away from the struggle of my parents back home and gives me hope of a bright future.”

“It is called a Pakistani school, but don’t be fooled by the name. These kids are more Indian than you and me,” said Govind Bhil, who helps run the school.

What inspires these young Indians are recent success stories of people like 36-year-old Neeta Kanwar. Neeta was born and brought up in Sindh. She came to India in 2001 with her mother and sister to pursue higher education while her father and brother, who were into farming, stayed back. Neeta went to Sophia College in Ajmer and got married in 2011. In September 2019, she got Indian citizenship and decided to contest sarpanch elections with the support of her husband and father-in-law, who was a three-time sarpanch. In January 2020, Neeta became the first-ever Pakistani Hindu migrant to have won a sarpanch election in the country.

“When I was getting married, my father could not come for my wedding because he did not get a visa,” said Neeta. “But today I realise, I am not disappointed because I’m not just the daughter of my parents. I have become a daughter of this soil.”