“I QUITE REALISE how hard it is to resist, with sage silence, the shafts of acid speech; and, how alluring it is to succumb to the temptation of argumentation where the thorn, not the rose, triumphs. In contempt jurisdiction, silence is a sign of strength since our power is wide and we are prosecutor and judge,” wrote Justice V.R. Krishna Iyer in a Supreme Court order that dropped contempt proceedings against a top editor in 1978.

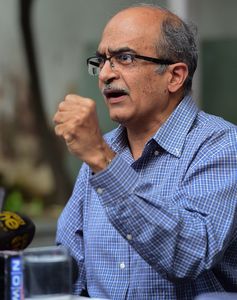

But the three-judge bench, comprising Justices Arun Mishra, B.R. Gavai and Krishna Murari, took a different approach in the Prashant Bhushan case. It held Bhushan guilty of contempt of court and levied a fine of Rs1, failing which he would be jailed for three months and debarred from practice for three years.

Two tweets made by Bhushan this June that raised questions over the functioning of the judiciary, the court concluded, “are scandalous and are capable of shaking the very edifice of the judicial administration and also shaking the faith of the common man in administration of justice”.

Legal experts, however, said that the Supreme Court overreacted and ended up getting entangled in a peculiar situation where the case could be perceived as a stand-off between the court and an individual. Bhushan’s counsel, too, had urged the court not to punish him as that would make him a martyr. Attorney General K.K. Venugopal, while disagreeing with Bhushan’s pressing into service various “objectionable statements” made in his pleading, appealed to the magnanimity of the court.

Supreme Court lawyer Shilpi Jain said that the court should have ignored the tweets. “I don’t think public sentiment was swayed to such a great extent by the tweets so as to conclude that they would shake the common man’s confidence in the judiciary,” she said.

The Attorney General’s interventions in court seemed to have facilitated the middle path that was seen in the ruling that levied a token fine despite the guilty verdict.

“You go through the motions and impose a symbolic fine of 01 despite the fact that Bhushan was recalcitrant,” said senior advocate Dinesh Dwivedi. “You tried to find a middle way. The attorney general’s views were a big factor. The court entangled itself in a situation of its own making.”

The alternative sentencing of imprisonment and debarment, said former additional solicitor general Bishwajit Bhattacharyya, was not only meaningless but also legally flawed. In the Supreme Court Bar Association vs Union of India case in 1998, the apex court had disapproved of a bench that debarred from practice a contemnor—advocate V.C. Mishra. The court said that the bench, within its powers, had punished him by suspending his licence, but without giving the Bar Council of India an opportunity to deal with it. It is not permissible for the court to “take over” the role of statutory bodies, said the court, and “perform” their functions.

Bhushan described the case as a “watershed moment” for freedom of speech, saying it had encouraged many people to speak up against injustice. But others in the legal fraternity said that the case would have major repercussions on freedom of speech. “History will look at the case as a very low point in the country’s jurisprudence, and this is certainly not a judgment to be celebrated,” said senior advocate Gopal Sankaranarayanan. “It is a poor judgment. It is effectively telling us that we cannot make any statements questioning the judiciary. It is a severe blow to free speech.” According to Jain, the big issue arising out of the case is the need to do away with the legal provisions for criminal contempt.