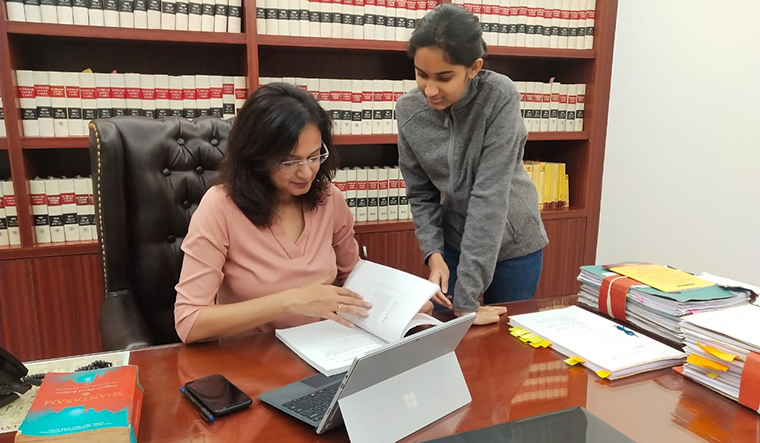

Malvika Trivedi wakes up early and, after her morning tea, heads for her home-based workout. She has set herself a 30-day challenge to build some muscle. Post breakfast, she gets ready for work as she would ordinarily do, even slipping into her sandals and never forgetting the lipstick. She then takes her two children, Adhrija and Darsh, downstairs to her office, where she sits down to work.

Work is not much these days, so the lawyer also surfs the internet or reads with her younger son, while her daughter attends her online classes. After lunch, they spend some time lounging together, and then she heads back to “work”. The evenings are spent watching Netflix with her husband, Saket, also a lawyer. “I am loving the lockdown phase, despite the heavy financial loss,” she says. “It has given me the time to be with my children, and remain stress free, too.”

Trivedi realised that her motivation to work had come down to zero when the court closed, so she forced a schedule upon the family. “I tried my hand at cooking, but the maids were petrified with the results, so I stopped,” she says with a chuckle. “I haven’t got bored till now, let’s see what the future holds.’’

In the surreal existence that the country, and much of the world, is now living, life has turned on its head. Three am is the new midnight, as one youngster put it. India, locked into the confines of its home, is valiantly trying to adjust to the new reality, and the host of challenges it has thrown up. While India went into lockdown from March 25, many parts of the country had already slipped into a semi-lockdown by mid-March. Even in Kashmir, which is used to curfews, and has just emerged from the lockdown following the abrogation of Article 370, the present time is like nothing before. Muezzins appeal to the devout to worship from home, and the security personnel compare it with the situation just a few months ago, when they had to work hard at maintaining peace and order.

The going is in no way easy. The initial days of panic buying and stashing up on provisions may have eased a bit with supply chains slowly falling into a system. But stuff one took for granted earlier is precious commodity today, even as so many objects of desire of the past life—cars, jewellery and clothes—have little meaning. The breaking of a television remote is an event high on the calamity scale, as one family discovered. And God forbid if the mobile phone decides to die out right now. Where once mothers stressed over ensuring their children did not miss the school bus, the equivalent of that stress shows up when the FTTH (fibre-to-the-home) connection snaps in the middle of an online class.

Working from home (WFH) is part of the new normal, but while it is a novel experience for those who commuted to work daily, even among communities where the WFH culture was already established, the experience is different. “With the domestic staff in its own quarantine, it is not WFH, but also all the work at home,” says an exasperated software professional Shwetha Rao, who finds herself facing laundry, cooking, cleaning and an endless string of domestic chores, along with her professional commitments.

Confined living is stifling on a number of counts. While the lockdown has given families time to bond, sometimes, there is also “too much family,” as Anhaita Puri, 21, says. The jokes about whether corona-babies will outnumber the corona-divorces are not funny anymore. Mumbai has already witnessed a ghastly corona-crime, a fratricide that resulted from a fight between two brothers because one of them had stepped out of the house.

Mental health will be one of the biggest challenges that society will have to tackle as the lockdown stretches out, and even beyond, when job losses will trigger a spate of domestic violence, mental breakdowns and suicides. Indeed, once the authorities are able to get a grip on housing, feeding and clothing them, the migrant labour that was left stranded will also have to deal with what to do with their spare time. Most are illiterate, and soon even the mobile savvy will run out of money to top up data. Their jobless hours could lead to several social and even law and order problems.

Rakesh Malviya, 39, however, might just come out of the lockdown smelling of roses, while his wife ought to develop heart-shaped pupils. The Bhopal resident has begun recording the daily routine of his homemaker wife, Anjali, with plans to make a documentary appreciating the efforts a homemaker takes to ensure the house runs smoothly.

If families cramming into personal, physical and mental space can get overwhelming at times, at the other end of the spectrum are those who live alone. Smita Vinchurkar’s life has become a gaping void. After her mother’s death last year, she was surrounded by friends and neighbours, and her solo living had not seemed like a problem. Now, the Mumbaikar feels “dull and depressed”. There is only as much television and films that one can watch, she says. As a freelance photographer, she is also facing the financial brunt of having no income. Vinchurkar has created a small distraction for herself. She poses for a selfie, self-times it and posts it on social media daily, documenting her lockdown life.

At least Vinchurkar is in her own home. Ekta Yadav, 25, and Ritika Dangi, 16, are confined to a hotel room in Colaba, Mumbai, and are the only two guests in that small hotel. The two yachtswomen were in Mumbai for training when the country began closing down in phases. “We missed even the last flight, and the roads closed, too,” says Yadav. “We later learnt there were four Covid-19 positive cases in that flight.” The girls have devised their own routines, which include a series of training exercises—light ones in the morning and strenuous ones in the evening. “We are sportswomen, we are tough,” says Yadav. “There is Netflix and television, and sometimes we like to prepare breakfast in the hotel kitchen ourselves.” A skeletal staff remains in the hotel, officials from the military help with other logistics, while their coach, now confined to his suburban apartment, keeps in touch over phone. In some ways, say the girls, it is better to be at the hotel than at home because they can train as a team.

Then, there are the parents. Self-sufficient senior citizens who lived by themselves. But, with them emerging as the most vulnerable age group, there is a heightened sense of insecurity. While families are no longer able to check in on them regularly, the drying up of their daily soap fix is another problem. Television serials have stopped production, though reruns of old programmes are adding to the semblance of stepping back in time. “We rarely stepped out anyway. But I am busier now, with so many chores now that the domestic staff does not come. I just hope we do not have a medical problem,” says septuagenarian Rehana Ziauddin.

The virtual world has come to the aid of youngsters and the old alike. From online classes to social media fora to discuss new recipes, life is now online. P.V. Kapur was one of those senior citizens who had an active life—his work as an advocate, as well as his social life, kept him busy. Till the lockdown restricted outings to a family dinner on the terrace. Then, he discovered the networking app Houseparty, which allows group videoconferencing. So, 7.30pm is now the highlight of his day, when his group of friends log in for a social get-together. “We have been together since the 1950s and we used to meet regularly. Now, we get our drinks ready—the teetotallers their haldi paani (turmeric water) or plain water—toast each other and chat. It is a bright spot when everything else is so bleak,” says Kapur.

If Houseparty is the new social watering hole, Zoom is the forum for work-related conferences. The younger generation is happier with multi-player online games like PUBG, which they were hooked on to anyway.

The lack of physical activity (for those who do not have endless chores) can get irking. Indeed, even as people worry about a shortage of supplies, they are as worried about new curves (and bulges) that will be a challenge to flatten. It took Muhammad Shafi all his skills and two days of hard work to make a swing on his lawn in Srinagar for his daughter Munazah and niece Aisha, both primary schoolers. The girls are happy, but for Shafi, the challenge will be to find some other activity now for himself. Necessity is the mother of invention, and one Delhi father, Dewan Kumar, made a Ludo board for his children from material at home—paper and colours. The dice was a challenge, till they decided to mould a bit of dough.

The phrase “window to the world” has never had more meaning than now, as people crane out of the grilles to take a glimpse at what is happening outside, which is not much except that urban fauna is getting bolder and more visible. Balconies have become the new outdoors, whether for a “picnic” lunch or for hobbies like balcony birding. Gurugram resident Prabhat Verma, armed with his camera, has spotted 30 species of birds from his eighth floor balcony, as well as jackals and mongooses, animals that cohabit urban space, but stay in the shadows usually. The cleaner air and clearer skies offer some great sky watching opportunity, too.

It is easy, however, to slip into despair and boredom. Thoughts of the raging pandemic are always at the forefront and with barely anyone resorting to digital dieting, the infodemic, too, continues to rage. Several groups are working on dealing with these issues. A group of doctors in Ahmedabad, consisting of pulmonologist Parthiv Mehta, gynaecologist Darshana Thakker and infectious disease expert Atul Patel, has harnessed social media platforms for Covid-19 information and myth busting. In Lucknow, Kulsum Talha, 60, journalist and teacher, has started a series of 21 inspirational stories from the lockdown. The idea was to keep her students, who seemed to be getting bored, motivated. The lockdown heroes come from all over India—a Mumbai teen who used a drone to send rotis to his hungry friend to a couple that takes care of stray animals. The youngest member of Talha’s team of five is 16. They get one version of their stories uploaded on a local newspaper’s website, and upload videos on social media themselves.

Meanwhile, the circle of life does not come to a halt with a lockdown. Across the country, there are deaths, not pandemic related, as well as births. Funerals are doubly tragic in present times, with even rituals having to be curtailed. In more savvy homes, last rites are shared with family members on group networking platforms, and there are even e-rituals available. In communally fraught Bulandshahr, a group of Muslim neighbours got together to give a Hindu funeral to a deceased neighbour.

A new mother in Mumbai has not been able to celebrate such a big event in her life. But her bigger problem is that there are hardly any clothes for the baby.

Even festivals have to be modified. The spring Navratri began on the day of the lockdown, and across north India, devotees wailed that they did not have a coconut to place before the deity. The kanya puja, during which prepubescent girls are venerated, also had to be modified, with video conferencing stepping into the void. A range of festivals—Mahavir Jayanti, Easter and the harvest festival of Vishu/Bihu/Baisakhi—will have to be adapted for lockdown life.

On the other side of the lockdown, what will the brave new world that emerges from the chrysalis look like? Is the present state a metamorphosis, or just a phase that will be gone with the wind?

With inputs from Tariq Bhat, Nandini Oza, Puja Awasthi, Prathima

Nandakumar, Sravani Sarkar and Pooja Biraia Jaiswal