IN JANUARY THIS YEAR, when the seventh tranche of electoral bonds went on sale, the response was impressive. Bonds worth Rs350.4 crore were purchased. In October 2018, just ahead of the assembly elections in five states, donors displayed an even bigger interest, buying bonds worth Rs401.7 crore.

In the run-up to the assembly polls, the government decided that electoral bonds will be sold in March, April and May 2019. On the face of it, a hike in donations to political parties just ahead of elections is not wrong. It ought to be welcomed even, since the avowed purpose of electoral bonds is to enhance transparency in political funding.

But serious questions are being asked about whether the scheme has ended up increasing the opaqueness in the system, and whether it only serves to legitimise the already entrenched nexus of corporates and political parties. These questions arise from an analysis of the scheme’s format and norms, and from the statistics related to it since March 2018, when the first tranche of electoral bonds was sold.

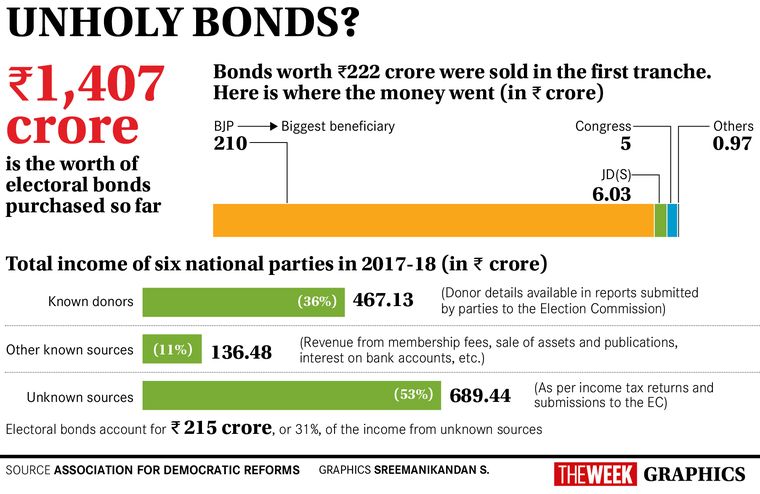

An analysis by the Association for Democratic Reforms found that, after electoral bonds were introduced, more than half the contributions to political parties came from unknown sources. ADR’s study of the contributions reported by political parties for 2017-18 found that 53 per cent of the Rs689.44 crore that was received came from unknown sources. While 51 per cent of this came from donations below Rs20,000, which can be legally anonymous, as much as 31 per cent came from electoral bonds.

This figure concerns only the first tranche. The impact of the remaining six tranches can be visible only in the contribution reports for 2018-19. In the seven tranches issued so far, bonds worth 01,407 crore have been purchased.

A matter of concern is that, under the electoral bond scheme, the donors remain anonymous. Introduced in the Union budget of 2017-18, an electoral bond is a bearer instrument that can be purchased from specified branches of the State Bank of India, and is available in denominations of Rs1,000, Rs10,000, 01 lakh, and Rs1 crore. The bond can be purchased by anyone with a KYC-compliant bank account, and it can be donated to any political party, which can encash the bond through a verified account within 15 days.

This means that the bank would have the details of the donors and the parties that have encashed the bonds, but political parties would not be required to reveal the donors in their accounting reports. The donor details, therefore, would not be available to the public.

Finance Minister Arun Jaitley has said that some element of transparency would be introduced through the scheme, whereby all donors declare the amount of bonds that they have purchased and all parties declare the quantum of bonds they have received. But he maintained that only the donor would know how much that person had contributed to a political party.

Experts feel that electoral bonds have opened the floodgates for corporate funding. They point out that there is hardly any demand for low-denomination bonds. Close to 90 per cent of bonds purchased are worth Rs1 crore each—an indication that the bonds are purchased mostly by corporate bodies.

“Electoral bonds do not increase transparency in election expenditure,” said former chief election commissioner T.S. Krishnamurthy. “On the contrary, this scheme will make political funding more opaque, as donors will remain anonymous and there is no limit on how much they can donate.”

Critics say the scheme, together with the 2017 amendment to the Companies Act that removed the cap on corporate contributions to political parties, will only strengthen the nexus of corporates and politicians. Earlier, companies could donate only as much as 7.5 per cent of the average of net profits earned in the previous three years. This cap has been removed, along with the requirement for corporate bodies to declare their donations to political parties.

“Now, even a loss-making company can contribute to a political party. If a company that is not in a position to pay dividends to its shareholders contributes to a political party, it would do so only for one reason—to cut a deal with the party in power,” said Vipul Mudgal of Common Cause, an NGO that filed a petition against the scheme in the Supreme Court.

Interestingly, the BJP received Rs210 crore of the Rs222 crore that went to political parties in the inaugural tranche of electoral bonds. The Congress got just around 05 crore, while its ruling coalition partner in Karnataka, the Janata Dal (Secular), got Rs6.03 crore. “The scheme clearly benefits the party in power,” said retired major general Anil Verma, who heads ADR. “This only denotes a quid pro quo between the donor and the ruling party.”

Former chief election commissioner S.Y. Quraishi said the scheme would legitimise and institutionalise crony capitalism. “Earlier, corporates would donate to all political parties. Now, since their identity will remain a secret, they can donate to one party—the ruling party,” he said.

With the removal of the restriction that permitted only profit-making entities to donate to parties, there is fear that shell companies could be used to pump black money into the political system. This concern was red-flagged by the Election Commission when the scheme was announced. In an interview with THE WEEK when he was chief election commissioner, O.P. Rawat had revealed that the commission’s concerns were not addressed by the government.

“When electoral bonds were brought in by the finance bill of 2017, the commission flagged certain issues. We said it would give rise to shell companies, and that companies which are not even making a profit might be used for political funding. We were told that it was just an enabling provision and no scheme had been formulated yet, and hence it was premature to say anything. So we waited,” Rawat said in the interview.

The commission recently reiterated its concerns before the Supreme Court, which is hearing petitions challenging the scheme. It said electoral bonds and the legislative amendments made with regard to funding of parties “will have serious repercussions/impact on the transparency aspect of funding of political parties”. In its affidavit, the commission said it had flagged the concerns in letters sent to the law ministry in May 2017.

Electoral bonds will open the way for foreign funding of India’s political system, say experts. Last year, Parliament passed an amendment to the Foreign Contribution Regulation Act, allowing Indian subsidiaries of foreign entities to contribute to political parties. “The government has opened the backdoor for foreign funding through the changes in the FCRA norms,” said Mudgal. “And electoral bonds could be used to donate to political parties here. This is a threat to the autonomy of the country.”

Experts say it would be interesting to see whether electoral bonds cause a corresponding decrease in funding through electoral trusts, which leave a paper trail. Funding through electoral trusts require several disclosures—like the identity of the donor and the beneficiary party, the mode of payment and the amount donated.

According to Verma, corporates are likely to prefer electoral bonds to electoral trusts. “A comparison of how electoral trusts and electoral bonds have fared,” said Verma, “will show if the former’s loss is the latter’s gain.”