THE INSTALLATION OF a popular government in Dhaka provides an opportunity for a reset in India-Bangladesh ties. Both countries must realise that there is no return to the close friendship of the Sheikh Hasina era. India would not want another security situation to emerge in the northeast, and Bangladesh is deeply tied to India for trade, transit and energy. Prolonged friction with India will rapidly raise Bangladesh’s strategic and economic costs.

As we assess the future trajectory of bilateral relations, both countries must seriously reflect on the reasons for the rapid deterioration in ties. In this context, five lessons stand out.

First, be sensitive to core concerns. Muhammad Yunus’s turn to an India-sceptical, China-Pakistan-leaning policy was too abrupt and predictably triggered concerns in Delhi. There were also very provocative statements on the northeast that further hardened India’s stance. India misread the depth of anti-Hasina sentiment in Bangladesh, and her statements from Indian soil were seen as an attempt to destabilise the government in Dhaka. With core concerns unaddressed, every small action led to a downward spiral in ties. While Bangladesh is free to determine its foreign policy, it must avoid any overcorrection that impinges on Indian security sensitivities.

Second, do not allow public sentiment to drive policy. In his meeting with Yunus, Prime Minister Narendra Modi specifically pointed out that rhetoric that vitiates the environment is best avoided. However, media narratives have raised tempers on both sides, with frequent protests around diplomatic missions leading to the suspension of visa services. The removal of a Bangladeshi cricketer from the Indian Premier League was the result of a social media campaign in India and prompted the Bangladesh cricket team to refuse to travel to India for the T20 World Cup. In the age of social media, popular sentiment cannot be ignored, but mutual concerns are better addressed through diplomatic channels rather than maximalist public statements.

Third, there is a need to guard against extremism. The attacks on minorities in Bangladesh were a continuous irritant in bilateral ties under the Yunus leadership. Given past history, there are genuine concerns in India about Indian insurgent groups finding shelter in Bangladesh and radical Islamist forces gaining traction within the country. If extremism develops strong roots in Bangladesh, there is a clear danger of its spillover across the border. Bangladesh has prided itself on a syncretic culture, and its erosion would be destabilising not only domestically but also for the region.

Fourth, policy must outlive personalities. One stark observation from this period is that a change in regime led to a complete reversal in Bangladesh’s foreign policy. Yunus, heading an unelected government, decided on a course of action that alienated India entirely. Delhi is also guilty of investing too heavily in Hasina, which was read in Bangladesh as a backing of the old order that had lost domestic legitimacy. Both countries must now frame policy from a perspective that looks beyond personalities to long-term national interests.

Also Read

- Fresh start in Dhaka: How Tarique Rahman's BNP govt is reshaping ties with India

- ‘No need to worry about Chicken’s Neck’: Kiren Rijiju

- Bangladesh at a crossroads: Can India counter the rising Islamist tide?

- ‘Foreign policy under BNP will be pragmatic’: Dr Ziauddin Hyder

- A vote for 1971: How Bengali nationalism secured BNP's election win

- A diplomatic tightrope: Navigating the complexities of India-Bangladesh relations

Finally, exploit the military-to-military relationship. Even during the period of strained relations, military contacts continued. During his annual press conference last month, Chief of Army Staff General Upendra Dwivedi said that military channels were open with the Bangladesh military to avoid any “miscommunication or misunderstanding”.

The Bangladesh army is a major player in the country. While it tacitly supported the interim government, it also nudged Yunus to hold elections in 18 months. Regular military contacts establish an institutional relationship that reduces the risk of diplomatic tensions spiralling out of control.

The Yunus period showed how quickly bilateral ties can unravel when they depend on personalities and narratives. A BNP-led government offers a window for some stabilisation if short-term political signalling catering to domestic constituencies can be replaced by respect for each other’s core concerns.

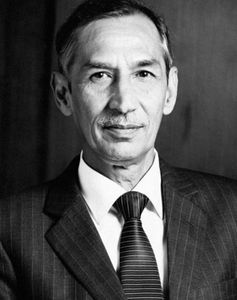

The writer is a retired Indian Army officer who served on both the northern and eastern borders. He retired as Army Commander, Northern Command