SRI LANKA

On a school holiday, seven-year-old Nitharshan from Neethipuram village near Mankulam in northern Sri Lanka went with his grandfather to his aunt’s house in Mullai Veethi for a family function. When the firewood ran out, his grandfather picked up an axe and set out to gather some. Curious and energetic, Nitharshan followed.

As they walked across a dry field, Nitharshan saw a strange metallic object on the ground. He picked it up and showed it to his grandfather. It was a 40mm shell, caught in a farmer’s plough and kept aside. The old man recognised the danger instantly and told him to put it down. Instead, the boy hurled it playfully towards a tree.

As it hit the tree it exploded and shrapnel flew. One piece pierced the boy’s face below the right eye and a few others cut into his torso and limbs. He collapsed, unconscious; shrapnel had entered his brain. A device of war had remained dormant for decades, like a seed of hate, to hurt a child.

Nitharshan was resting on his mother Thenuja’s lap when I visited their home. His eyes closed often and, when open, gazed blankly. Thenuja is a surrendered rebel fighter. She lost two fingers in the war for Eelam, but her combat wounds have healed. The people have largely forgotten the war, but the land remembers.

Sri Lanka looks like a droplet frozen in time. That very shape is a haunting reminder of the tears shed during decades of civil war. The emblem of the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam, which waged the war, was a tiger baring its teeth and claws, but the territory once claimed by it—the northern and eastern provinces—resembles a raptor’s claw clutching the island. When the war ended in 2009, the raptor’s claw had around 15 lakh landmines and unexploded ordnance (UXO), making Sri Lanka one of the most heavily mined countries in the world.

Across the scarred landscapes, humanitarian deminers work tirelessly to spot and remove the hidden danger—scanning the ground inch by inch. The painstaking process resembles an archaeological excavation, except the aim is to erase a part of a terrible past.

The north of Sri Lanka feels like Tamil Nadu. Rows of palmyra palms sway in the dry wind, dravidian-style temples stand in open fields. In roadside eateries, owners with sacred ash on their foreheads sit beneath pictures of Hindu gods adorned with jasmine garlands. Tamil film songs play in the background, mingling with the aromas of sambar, dosa, idli and vada. Not many tourists are seen here.

The Sinhala-speaking southern Lanka feels like Kerala—lush, humid and smelling of the sea. Foreign tourists flock to the beaches and bars. Representations of the Buddha are ubiquitous. The difference in landscape mirrors the divide between the communities.

Half of the landmines in Sri Lanka were in Jaffna. The northern peninsula is the cultural capital of Sri Lankan Tamils. The LTTE controlled the region for about a decade until 1995.

Though mines were used since Eelam War I (1983-1987), their number grew substantially during Operation Pawan by the Indian Peace Keeping Force in 1987. It increased further at the beginning of Eelam War IV in 2006.

Landmines were laid near frontlines to inflict damage, and to protect infrastructure—bridges, camps and arms factories. Some were anti-vehicle (AV) mines and some anti-personnel (AP)—even 7kg of pressure can detonate them. Directional Claymore mines were also used. The idea was not always to kill, but to maim, reduce enemy strength and slow advances.

The Sri Lankan army used mass-produced mines like Pakistan’s P4, Italy’s VS-50 AP and Chinese Type 72A AV. The LTTE developed its own—Jony 95, Rangan 99—named after killed commanders. It also used IEDs, recovered mines and booby

traps in plastic oil cans, pots and buckets.

The Elephant Pass and the Jaffna lagoon separate the peninsula from the mainland—the Sangupiddy and Elephant Pass bridges now connect them. On losing Jaffna in 1995, the LTTE retreated to the districts south of it—collectively called the Vanni—and fired artillery across the lagoon.

A few months after the war ended, a young fisherman named Rasaiah Santhiran went out to the Jaffna lagoon. He needed long sticks to anchor his stake nets. He paddled to the Kannativu islet, looking to cut the branch of a tree.

As he walked through the shrubs, a mine exploded under his feet—shredding his lower leg. Bleeding and in shock, he dragged himself back to his boat and somehow reached a mainland hospital. Nobody had thought until then that Kannativu and two other uninhabited islands—Mantivu and Puvarasantivu—had been mined. New minefields are often discovered through tragedies like Santhiran’s.

Mantivu is now being cleared by The HALO Trust—the world’s largest humanitarian demining organisation. It began operations during a 2002 ceasefire and cleared three lakh mines by mid-2025. According to Hugh Baker, programme manager, Sri Lanka, it is the second highest number of mines that have been located and cleared from the ground by HALO anywhere (after Cambodia). The work is largely in Tamil majority regions and most of the workforce is Tamil. HALO is the second largest employer in the Northern Province; it once employed over 1,200 local people. But, the number has now fallen below 1,000 because of funding cuts and attrition. Many of the workers had suffered in the war.

Vithoozen Antony, operations manager, HALO, took me to Mantivu on a motorboat.

As we approached the shore, we could see red signboards, DANGER MINES!, in English, Sinhala and Tamil. Lines of red sticks in the ground marked danger areas. A demining operation was going on behind thick bushes. Because of humidity, deminers get 10 minutes of rest after every 40 minutes of work. During a break, deminers resting in the shade told their stories. One of them, Thasitharan Kalaiselvi, said she was proud her work would make the land safe again.

After the break, deminer Inthira Priyatharsini took out her metal detector, calibrated it on the sandy ground and swept carefully. On getting a signal, she marked the place with a red chip and scraped through the soil towards it with a trowel until an object was revealed. Even if it turns out to be scrap metal or a stone, she must treat every signal as deadly. Most modern landmines have minimum metal content, to make detection hard.

Next, we drove to Muhamalai, the densest minefield in Sri Lanka. It was the LTTE’s main defence line; if the Sri Lankan army broke through, it would gain access to the Elephant Pass. Mechanical demining works best in Muhamalai as the former farmland is marshy with open fields. An armoured excavator carefully lifted soil and droped it into a sifting machine that separated stones and metallic fragments. Teams of women led the operations there.

The next morning, we were at HALO’s base in Kokkuthoduvai, a small village near Mullaitivu. This base oversees the demining at Andakulam jungle. At dawn, deminers in cargo trousers and black boots had lined up for the daily drill, to listen to safety protocols and to collect their tools—secateurs, scrapers, strimmers, mine detectors, visors and blast-proof jackets. Each team has a member trained for medical emergencies, marked with a plus patch. Trucks carry workers to the task area.

We drove through a waterlogged road into the jungle. It felt ancient—a dense web of canopy and thick creepers around old trees. Saplings have reclaimed the floor once disturbed by war. An impenetrable wilderness hiding elephants, leopards and bears for years it also hid the Tamil Tigers. The red sticks in the ground contrast with the greenery.

During the war, if either side wanted to breach a mine line, they relied on explosive ordnance disposal (EOD) teams. These sappers (military engineers) located and disarmed landmines and booby traps. The military also used Bangalore torpedoes—mine-clearing explosive charges developed in Bengaluru in 1912, first used by the Madras Sappers and later adopted worldwide.

Humanitarian demining is different. It demands patience, precision and attention to every inch of land marked as a confirmed hazardous area. Walking in the forest, I found men and women in blue bomb suits scanning and scraping the ground in a cleared patch. Despite the threat of wild animals, they worked with soldier-like discipline, moving slowly, eyes fixed on the earth, alert to signals. The once rugged and wild floor soon looked swept as if someone was building a Zen garden.

The team commander’s wireless crackled—an RPG had been found. Another message followed—a Rangan mine detected. We headed to the spot; but even with protective gear, we were not allowed near. Once a mine is discovered, only an EOD specialist can neutralise it. Meanwhile, there was a long whistle for a casualty evacuation drill.

Deminers scattered across the terrain moved toward the assembly point. A kneeling paramedic unzipped a huge medical kit and laid out bandages, syringes and IV tubes. Four men carried a young man with a ‘wounded’ silicon hand on a stretcher. The paramedic, assisted by others, gave him first aid, tying a tourniquet, bandaging the fake wound and fixing an IV line. The man was then carried to an ambulance. Though it was a mock drill, there was no hint of amusement.

On my way back, there were small, yellow wooden pegs bearing black letters and forming a wavy line marking spots where Rangan mines were recovered. Mines were normally buried about 1cm to 5cm deep, but years of rain, erosion and shifting soil could have altered their positions.

Further along, we stopped at the remnants of an LTTE bunker. Even in ruins, it was impressive. The thick concrete walls had ventilation shafts, a massive elevated water tank and an open-air washing area. Tunnels connected bunkers through multiple entry and exit points. Inner walls still gleamed with tiles. Faint writings remained etched on the cement floor. One read: “Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam, 8.9.1990.” On a pillar nearby, white paint spelt out “7 GW”—the 7th Battalion of the Gemunu Watch of the Sri Lankan army.

A few kilometres away is a settlement called Weli Oya, the Sinhala name for what was once known as Manal Aru (sandy river). During the war, Tamil families were reportedly evicted and Sinhalese settlers were brought in. But even those resettled have not escaped the hazards of the war. Senanayaka, a Sinhalese farmer, accidentally stepped on a landmine near the village’s border and lost a leg. He now drives a tuk-tuk in Colombo. Stories like his are not rare. Danger hides in the ground everywhere, even schoolyards. Earlier this year, UXO were cleared from a school playground along the Mullaitivu-Kokkilai road.

Compared with Andakulam, the forests at Vannivilankulam near Mankulam, where the Mines Advisory Group (MAG) is demining, felt distinctly man-made. During the LTTE years, thousands of teak saplings were planted here.

MAG, an international humanitarian demining organisation, was a co-laureate of the 1997 Nobel Peace Prize for its campaign to ban landmines. Field operations manager Naguleswary Nachimuthu greeted us with a soldier’s precision. After a briefing in a thatched room by technical field manager Biagio Disalvo, Nachimuthu repeated the safety protocol in a voice that left no room for doubt: “When you enter the task area, you follow my path. If you wish to move for photography, inform me first.” At the entrance, rusting mortar shells and RPG tails collected from cleared areas were neatly stacked.

The teak plantation, which once witnessed the war, now sees former enemies working to undo its lingering impact. Ziggy Garewal, country director, MAG, Sri Lanka, said former LTTE combatants and former Lankan army personnel were among the deminers. “Now the relationship between them is more cordial,” she said. “Obviously as time goes on, people get over some of the harshness of the conflict. They are all working together.”

We moved under the teak canopy as the army’s EOD team arrived to destroy recovered explosives. An officer in a blast-proof suit collected recovered mines, placed them in a sandbagged pit and retreated. Smoke rose after a loud blast. Each controlled explosion frees another patch of land. But, most minefield maps have been lost or were never made. Operators rely on former LTTE fighters who buried the mines. The memories, though imperfect, are invaluable.

As per the National Mine Action Centre (NMAC) 1,332sqkm land was contaminated after the war, including suspected hazardous areas. Now, about 22sqkm remains to be cleared. The country has pledged to be mine-free by 2028, but that appears unlikely because of funding shortages and the discovery of new hazardous areas. Yet, the progress is giving communities hope.

In Muhamalai, Rasadurai Rajendran, 64, waited 22 years to return to his land. Now, his five-acre farm is alive again. “Because the land is being dug up by excavators, snakes have come this side,” he said, watching his dogs bark near the fence. “They keep barking all the time.” But, his faint smile reflected quiet contentment.

Across Mannar, similar stories unfolded. Retired police officer Lal Senaviratne’s land was cleared twice, each time revealing hundreds of mines. “My mind is free because my land is mine-free,” he said.

Younger people, like Praveen Selvakumar, 26, have grown up with risk education. When his plough unearthed mines, he stopped work and informed the police. At a school in Kanakarayakulam, children learn to recognise mines through awareness sessions conducted by a MAG team.

Thenuja points to a large scar on Nitharshan’s head. The wound was not caused by the blast but by medical complications that followed. After the explosion, in 2023, he was moved from one hospital to another. First in Mankulam, then in Kilinochchi and finally Jaffna. He was in a coma and the family had lost hope. But soon after arriving in Jaffna, Nitharshan regained consciousness and whispered: “Amma.”

Doctors found shrapnel in his brain. Other injuries were treated quickly and surgery was performed on the back of his head to remove the shrapnel. But, the doctors closed the scalp without completing the treatment—the family could not afford it.

Nitharshan survived with partial paralysis and blindness in his left eye. He now goes to school without a part of his skull. He always sits close to the wall, careful not to let his classmates accidentally touch his head. Recently, the family was told that the stored skull fragment had turned brittle and crumbled.

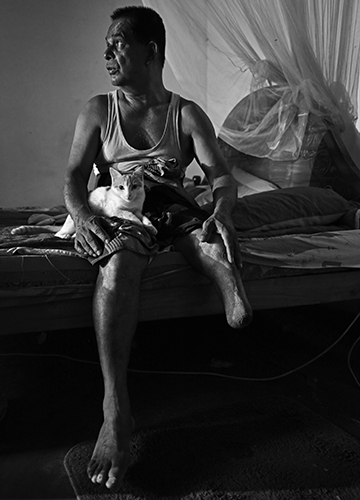

There are many landmine victims in Neethipuram. One of them is Thenuja’s brother-in-law Murugesh Pushparasa, a former LTTE fighter. He was 19 when he was injured in 1997. “I was hit by a dappi” he said, referring to a P4 mine. His comrades carried him to hospital on a motorbike. He lost his right lower leg and is a cook in a small hotel.

Thenuja’s husband, Partheepan, was also a fighter. They fell in love in a rehabilitation camp and had three daughters besides the son. She never imagined she would be a mother. As part of the Malathy Brigade, she had handled RPGs and taken part in several battles. She lost a finger on each hand in a shell explosion.

When the LTTE was cornered in Mullivaikkal in May 2009, she surrendered at age 19. As she walked to the army’s side, she saw a woman torn apart by a mine and others collapsing from hunger and thirst.

She explained why the LTTE failed: “In the final phase, younger recruits who were forced to join had no motivation to fight. My friends and I wrote a letter to Thalaivar, pleading not to recruit the unwilling.” But, she was not sure if the letter ever reached the leadership.

In 1991, Thandikulam was the border between the LTTE and government forces. A farmer, Veerakatti Vetrivelayuthapillai, lived in LTTE-controlled Vannivilankulam but was allowed to cross into Vavuniya for work. Once, while waiting at the checkpoint, the LTTE ambushed the post. The army retaliated. Caught in the crossfire, Vetrivelayuthapillai ran towards an open field and stepped on a landmine that blew off his right leg. He was taken to the Vavuniya military hospital. His family, who were searching for him, learned about it two days later.

He has not given up. With his artificial leg, the 73-year-old pedals his bicycle to his plantain farm. He needs a new prosthetic leg, as the current one no longer fits because of age. “Every landmine victim is entitled to a pension of 10,000 rupees,” he said. “But, I have not received it.” He lives in a house built under the Indian Housing Project.

Kandaiah Vijayanandan, 55, of Thirunelveli, Jaffna, stepped on a mine while herding goats in 1996. He lay bleeding for several hours fearing the army. After interrogation, he was taken to a Jaffna hospital. He lost the lower part of his right leg and spent two years recovering. Later, he trained himself to climb palm trees using a Jaipur foot and makes toddy. Seeing him climb with a can and tools around his waist is scary, but he moves with ease, disappearing among the leaves. “I can take care of myself now,” he said. “But I worry about [growing old disabled].”

The tragedies add up across northern Sri Lanka.

In 2000, between the Thondamanaru lagoon and Palali airport in Jaffna, Sivapadan Thasitharan, then 20, was tilling his rented land at dawn when a landmine exploded beneath him. He woke up with an amputated leg. Now married with two children, he runs a bicycle repair shop and is the family’s sole breadwinner. His only request is a western commode. He said a farmer recently found mines in his tractor’s track.

In 2003, day labourer Velu Mohanraj from Ganeshapuram was collecting firewood when it drizzled. Hurrying, he stepped on an army mine and spent four months in hospital. The injury led to gangrene and the amputation of his left foot. Now, he has diabetes and kidney disease, too. His wife, Kannagi, a cook, said: “We got only 25,000 rupees as they said 50,000 is only for right leg injuries.”

Karunanithi Yasothini, 39, from Nelukkulam is a single mother of two. She joined the LTTE at 20. She started in the administration wing, but was sent to fight in 2008. She thinks she stepped on an LTTE mine replanted by the army. She tried reaching for the ‘kuppi’—cyanide capsule—around her neck, but it was entangled in her clothes. Her mutilated right leg was removed below the knee. After the war, Yasothini received a government job as a development officer. “I miss the old life; there was a sense of purpose,” she said. Her new mission is to give her sons a good education.

She is ineligible for disability grants as a government employee and most of her salary goes towards maintaining her prosthetic leg. She posts modelling photos with her artificial leg and contested the 2024 parliamentary elections from Vanni. “I got only 1,700 votes,” she said. “But for me, that is really big.” Her sons sat beside her watching cartoons on a laptop. She would never tell them how she got injured.

Sri Lanka’s middle-aged generation carries wounds of war—some buried deep within, others visible. Look closely and you will notice men and women limping; look longer and you will see plastic or fibreglass limbs. The victims are not limited to civilians or Tamil fighters.

Nimal Karunathilaka, a Sinhala EOD expert, was injured while disarming a P4 mine in 2018. “Everything was done by the book,” he said. “But, old mines can be erratic.” He lost part of his left hand and several fingers on his right. His first responders were fellow deminers who were former LTTE fighters. Karunathilaka works in the NMAC regional office in Kilinochchi overseeing mine clearance completion surveys.

On my way back from the north, there were fruit shops lining the highway at Maradankadawala near Anuradhapura. The driver, Gamini, wanted TJC mangoes (named after two scientists who created the variety in Sri Lanka). After the shopkeeper weighed the mangoes, he reached for a carry bag beside a Ganesh idol. As he moved, we noticed him limping. His toes barely moved—it was an artificial limb, carefully matched to his skin tone. The 54-year-old—T.N. Wimalasiri—fought in the army and got injured by an LTTE mine during Operation Jayasikurui in 1998. Now he lives on a modest pension and a small income from his fruit stall.

Many Sinhala men joined the army as patriots, but many others did it to feed their families. Thousands, who were lucky enough to survive the war, now live as injured veterans.

They are called ranaveeru. Across the country, several settlements—ranaveerugama—built by the government house them. I visited one such settlement near Ibbagamuwa in Kurunegala.

Ekanayake Bandara, a former soldier of the Gajaba Regiment, was injured by a mine in 1991. Now, he drives a tuk-tuk and serves as president of the Ranaveeru Welfare Society. A walk through the lanes is both haunting and inspiring. A soldier who lost both arms sprinted carrying a freshly fallen coconut between his elbows.

A Gajaba Regiment soldier, M.G. Dayananda, lost his leg to a landmine in the Wilpattu forest. “I am happy mines are being removed; it will reduce danger for the next generation,” he said. “But, because of the economic crisis, our pension value has dropped and the price of essentials has skyrocketed.” His words echoed the frustration of many ranaveeru who feel a rise in pension is needed.

At the community centre, wives and daughters of the injured gathered for a zumba class and Bandara brought a dozen soldiers to share their stories.

I was the first victim of Eelam War II after the IPKF left Palali,” said former air force officer Prasanna Kuruppu, who lost both his legs to a mortar shell at the Palali airport. “My concern now is not my disability, but the lack of strong policies for the disabled in this country.” He is one of Sri Lanka’s leading disarmament campaigners and president of Rehab Lanka, run by the disabled. One of its key initiatives is training the disabled to make wheelchairs.

It is estimated that Sri Lanka has had 22,000 landmine casualties since the 1980s. The number could be higher as there are gaps in the data. The mines remain a persistent legacy of conflict. They do not distinguish between soldiers, civilians or animals. The elephant Sama had her right front leg blown off when she was a calf. She lived out her life at the Pinnawala Elephant Orphanage.

Also Read

- 'Landmines never really stopped an enemy': Vidya Abhayagunawardena

- 'Sri Lanka is a success story. We have completion in our sights': Peter Hugh Scott Baker

- 'Former LTTE combatants, army personnel working together to clear Sri Lanka’s mines': Ziggy Garewal

- Clearing the past: Inside Sri Lanka's National Mine Action Centre

The Galle Face Green in Colombo has witnessed many storms over the years. Most recently, it saw the Aragalaya democracy movement. Now, mass protests are banned. But, a group of retired soldiers sat across the president’s office. Some were in wheelchairs, others placed their artificial legs on the pavement. Many were landmine victims demanding a better life.

In the north and the east, on May 18 every year, the Tamils gather for Mullivaikkal Remembrance Day for the dead and the disappeared. Many take risks just to attend such events. In Jaffna, loud emotional songs are heard at the site where LTTE leader Thileepan fasted to death in protest against India. The military removed his statue, but red and yellow flags fluttered in defiance as people assembled to show solidarity. Many of them bore injury marks. Siva, a school teacher, approached me and whispered: “India betrayed us.”

The Indian Cultural Centre is today the tallest building in Jaffna. Once the mines are cleared, tourism and development may come back. Then there will be more buildings competing to be the tallest. For now, the victims’ issues need to be addressed by the authorities on high priority.

As the world witnesses new wars driven by faith and ideology, Sri Lanka’s forgotten war stands as a warning—the weapons we hide will haunt us long after peace returns.

40% of civilian casualties of mines/erw globally since 1999 are children.

As per the UN, a landmine costs $3-$75 to make and $300-$1,000 to clear.

Globally, On average, 17 people were killed or maimed a day by mines/ERW in 2024.

51countries recorded mine/erw casualties in2024.