DELHI

ON A CRISP winter morning in Delhi, Harmanpreet Kaur pulls into the driveway of THE WEEK’s guest house in Golf Links. The 2025 World Cup-winning captain—sunglasses on, hair tied back—has driven herself from Gurugram. Her manager Nupurr Kashyap tells us she loves to drive, but rarely gets the chance. Harman saw an opportunity and took it.

Does she not worry about getting recognised on the streets? “If someone spots her, she’ll fold her hands and smile,” says Kashyap, also her closest friend. “If she doesn’t want to be recognised, those sunglasses do the job.”

The first thing Harman does after stepping out of her SUV is shake everyone’s hand. She asks for a black coffee and, as soon as she gets it, she asks her team if they got their refreshments, too.

We show them to their rooms—Harman enters, drops off her luggage and moves into Kashyap’s room. There they sit, chat and rest a bit before the shoot.

When it’s time to choose one of her outfits for the camera, she has two options: a bright-pink or pastel-green lehenga. With no hesitation, she chooses the pastel. Loud jewellery isn’t her style. She has an instinctive comfort with certain silhouettes, especially in athleisure. She gets into the first look and sits down for the interview. As I begin, she leans forward, fully present. For years, India has known her as the woman who bats like a storm. But behind that power-hitter is a small-town girl who forgets phone chargers in hotel rooms, looks for a gurdwara on every foreign trip and turns to guru paath (reading or recitation of Sikh religious texts) when alone.

She speaks about her journey, her mistakes, her team and the version of herself she wants to become. Kashyap jokes that Harman has two settings: “match mode” and “everyone-is-family mode”. But, even in the latter, the captain’s instinct doesn’t switch off. “She’s observant to a fault,” says Kashyap. “She’ll notice if someone is uncomfortable in a room right away.”

Harman began as a wide-eyed teen—she loved cricket, but didn’t know there was a national women’s team. “Mujhe TV par aana hai, mujhe Sehwag pasand hai, mujhe blue jersey pehanni hai, par shayad main ladkon ke saath kheloongi (I wanted to be on TV, I liked Virender Sehwag, I wanted to wear the blue jersey, but I thought that I would play with the men),” she recalls.

After all, she had only ever played with the local boys in Moga, Punjab.

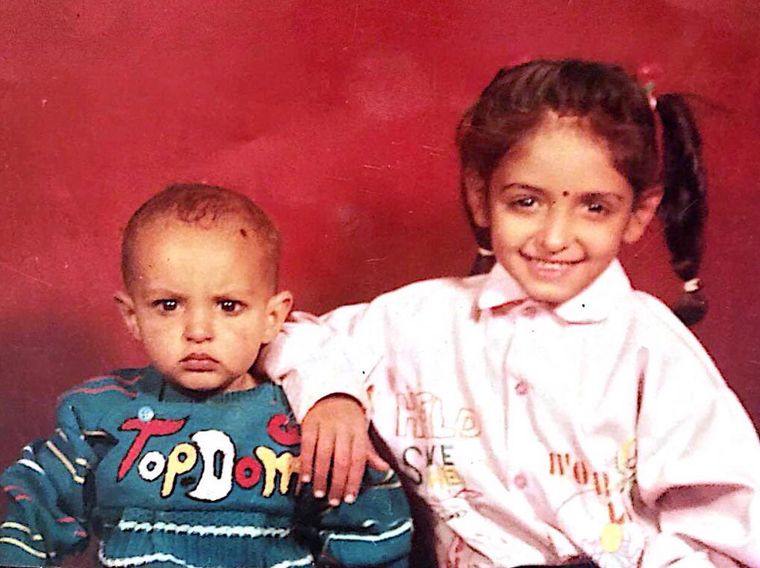

Her parents, though, never let gender shrink her world. The neighbours might whisper, “She’s growing up, why is she playing with boys?”, but at home, no one stopped her. If her father hit a 60m six, she believed she should do it, too. Her brother played hard, so she played harder. The aggression people now see in her game is really just that early conditioning.

“When I was playing with boys, my aggression was totally different,” she says. “With guys, you can get away with anything. With girls, sensitivity was a crucial aspect. So, I changed myself. Earlier, I was casual, fearless and careless; now it was about being more professional and thoughtful.”

This became more important when she became captain. Says Ganesh Balachandran, a cricket fan who has closely followed Harman’s journey: “Women process pressure differently, lean into sensitivity differently, and it took time for her to translate her instinctive steel into leadership that could hold an entire dressing room.”

When she started, Moga was hardly on the cricketing map. Harman, in fact, was part of the earliest girls’ teams in the district. Kashyap, who was from Patiala, a city with deep cricketing roots, recalls how the two first met in an under-19 tournament. “Harmanpreet was that girl who always sat quietly in the bus,” says Kashyap. The girls from Patiala and Chandigarh had their own circles and Harman would quietly take the corner seat. One evening, after a game against Hyderabad, the team made dinner plans. Someone pointed out that there was one girl who never spoke. Kashyap asked why nobody included her. “My friends said, ‘She doesn’t talk to anybody. If you want, you go ask her.’” So she did. “I went to her and said, ‘Harman, do you want to catch up for dinner? We’re going back to Delhi tomorrow, and it’s an off day, sightseeing and all, so tonight everyone is sitting together.” Harman looked at her, almost startled. “Me?”

The innocence of the response struck Kashyap. No one had ever invited her out before. She accepted the invitation, sat at a long table with 15 girls and actually spoke. Under-confident, but trying. It was the first time the team really saw her. And since then, the two have been inseparable.

Harman didn’t have a phone back then. Kashyap would call her landline. “She wouldn’t speak much, she just didn’t know how to talk on calls,” she says. Harman was preparing for her board exams, and every check-in sounded the same: “How are your exams?” “I’m studying,” Harman would say. Kashyap would laugh and tell her to focus, reminding her that class 12 was important.

One afternoon, Harman finally revealed the reason for her silence. “You speak English… I don’t know how to reply to you,” she said. “What do I even answer?” This surprised Kashyap. “We worked hard on communication together,” she says. “First, just to break the barrier between us. And she, to her credit, always had that desire to learn.”

There was another moment that stayed with Kashyap. Harman had just hit 47 runs off 18 balls, coming in at no. 9. “I told her, ‘Harman, you will play for India. I feel it,’” she says.

Somewhere in a drawer, Kashyap still keeps the first autograph Harman ever signed—it was for her. It sits in the pages of her old notebook. “I would tell her, ‘Tomorrow, when you sit in press conferences, this is how you will talk.’ We had started manifesting a lot of this back then itself,” she says.

The early years, though, were marked by uncertainty. “Back then, there weren’t so many facilities and job options,” recalls Harman. The Indian Railways was among the few lifelines for women who wanted to play and have a job, too. “Since winning the World Cup, girls are getting offers from their states… everybody is becoming a DSP,” she says. “Back then, even though I was playing for India, I did not have enough money to spend on myself or my training.”

It is only in the past few years that the landscape has changed, especially with the arrival of the Women’s Premier League. “After the WPL, one doesn’t need to worry about a job and can focus on cricket,” says Harman. The league has brought financial security and also an alternative pathway to the national side. “Now we are financially stable enough to spend on ourselves and our game,” she says. “We can finally see the improvement we had always talked about.”

In an interview that lasts over two hours, Harman never shows any signs of hurry. Kashyap has to remind her to sip water every 30 minutes or so. “She’s not used to speaking so much,” she says. “I am sure she will come after me when this gets over.” Harman chuckles and says, “No problem.”

When Kashyap first began managing Harman, one of the early hurdles was perception. Brands felt as though strength and athleticism had to be softened for public consumption.

But beneath the toughness that people see lies a softness only a few know. Harman is gentle with her sister, protective of her mother and quietly affectionate in ways that contradict her on-field persona. Those close to her would say that it is not her aggression, but her empathy and emotional intelligence that define her more. Kashyap recalls a moment during a tough phase. “Everyone reads everything,” she says. “But Harman has this rare ability to not react. She processes it and responds later, only if needed.”

In a career defined by big moments, it is often the small ones that have shaped Harman the most, especially some conversations with coaches. W.V. Raman, former head coach, remembers her as being “highly intense” in the early days of his stint. “I took charge of the team in 2019, and, gradually, as she gained experience and the nucleus of the team started forming, she became calm both as a batter and a captain,” he says. “This has benefited her and, as an extension, the team as well.”

Harman agrees. “Earlier, I used to get angry at every small thing—and it showed. Everyone could see it,” she says. “Over the years, I’ve learnt to control my impulses. If something upsets me, it doesn’t show the way it used to. I’ve worked on myself a lot. I just wish I had learnt this earlier.”

To the girls coming through, her advice is simple. “When you enter the senior team, you’re not a junior any more,” she says. “The day you understand that, your game will grow. If you keep saying ‘I’m small, I’m a junior,’ you’ll never fit into the senior squad.”

A perfect example is Shafali Verma, the player of the match in the World Cup final. When the prodigy joined the national team in her teens, Harman made sure she saw herself as part of the team and not as a temporary guest. Responsibility, not hierarchy, is Harman’s leadership mantra.

She had found similar support when she was called up to the national team in 2009. She had just played zonal cricket with Anjum Chopra, who had immediately seen her potential. Chopra and Jhulan Goswami, the seniors, watched over her and shielded her from distractions.

To Harman, leadership is equal parts skill and emotional availability. “My job is to give them room to fly,” she says. “I just want to be someone young girls can look at and say: ‘Okay, she stayed true to herself.’ I don’t want perfection. I want progress. Even if it’s 2 per cent better with every effort, that’s enough.”

Captaincy taught her to listen, to be soft, to understand the emotions of young women who came from different backgrounds. “It gave her a new kind of stability, a calmness and patience that didn’t exist in the early years,” says Balachandran.

Off the field, Harman is low-maintenance. “She will step out for chaat, wander through a mall with a mask on, insist on doing the most ordinary things in the most ordinary ways,” says Kashyap. Once, she asked Harman to wait in a mall’s car park for a few minutes. When she returned, Harman had slipped out, a scarf over her face, and was happily roaming inside. Another time, they were headed to an IPL match in Bengaluru. Their car didn’t come on time and Kashyap suggested they wait. Harman refused. “If it’s a five-minute walk, why waste an hour waiting for a car? I’ll run and reach there. Will you run with me?” Finally, they took an autorickshaw.

Harman’s idea of a break is a quiet meal and binge-watching series. Her favourite shows are CID and Crime Patrol—she has downloaded entire seasons of both and watches them on loop. “She just goes on watching without even registering the title or the name of the filmmaker,” says Kashyap. “She’ll watch good content, irrespective of the language.”

When it comes to luxury items, though, Harman is particular. On the day she meets us, we see an enviable collection of stylish, branded shoes. “Harman’s relationship with luxury is simple: if she loves it, she buys it,” says Kashyap, with a laugh. “Shoes, watches, sunglasses—those are her three weaknesses. She doesn’t ask the price, doesn’t compare, doesn’t save them for a special occasion. She wears them straight out of the store, tags off, box discarded. It is her one unapologetic treat to herself.”

Harman insists on carrying a new pair of shoes every time she goes on tour. Clothes are planned down to the last day. “Yeh tour ke kapde next tour mein nahin aayenge (these clothes won’t come along for the next tour),” she says.

When they feel the need to unplug, Harman and Kashyap go to Moga. The first trip there was one of Kashyap’s favourite memories. Everyone sits together, hot food is served without fuss and the lights are out by 7pm. “It felt like detox,” says Kashyap. Time spent in Moga restores them.

On the road, Harman protects her mental wellbeing by meditating. The rule is simple: no negative words, no negative frequency. “She dislikes chaos, lingering tension and too many changes once a plan is set,” says Kashyap. Her mother’s philosophy is her emotional compass. “There are two teams—one wins today, the other, tomorrow,” she once told her. “You don’t end your life over it.”

Another thing her mother told her: “Don’t buy a bike.” The family knows the thrill-seeker in Harman. “She loves biking, parasailing, anything that carries a rush,” says Kashyap. “In another life, she would have been the first one off a cliff, harness strapped, wind in her face.”

Unfortunately for Harman, being on a BCCI contract means she cannot pursue anything too dangerous. “I manifest having my own bike and going on road trips,” she says. “If I ever do get a chance, I will buy a high-end bike.”

For someone so fearless, she has one dread: reptiles. Cats, however, are a different story. She adores them. Once, in South Africa, she even fed lion cubs. “There is a quiet understanding between them; from house cats to wild ones, she has a natural connection with the entire feline family,” says Kashyap.

She has their curiosity, too. Especially when it comes to gadgets. “If something breaks at home—a fan, a lamp, even a toy—she must fix it,” says Kashyap. “A new device at home means the entire day will be devoted to seeing how it works. She thinks mechanically and can spend hours repairing or tinkering with things.”

What she gets bored of quickly is posing for photos. “Playing cricket is much easier,” she quips, while posing for a shot. “Of course, when I see the pictures I love it and know that all that time was worth it, but in that moment, it feels tough to stand and pose.”

Was there an outfit she was sceptical about but it turned out great? “There was this one outfit I wore on The Kapil Sharma Show,” she says with a laugh. “Just a few days ago we shot for the show, and Nupurr made me wear an Indo-western dress I was absolutely not comfortable in. As sportspersons, we’re always in casuals, so the first time I put it on, I actually started fighting with her. For three-four minutes we argued properly. But then I saw the pictures and videos later… I liked it.”

Harman is not too active on social media, where most of such shoots end up. But she did dabble after lifting the World Cup. “The winning moments… the Reels… I keep watching them on loop,” she says. What about a whole movie on her life? “I won’t give interviews, you’ll speak,” she tells Kashyap.

If that movie does get made, expect a lot of shots of Harman in the gym. It was on an early tour to Australia that she had this realisation—India did not lack cricketing talent, it lacked fitness and energy. She would see the tall, toned Aussies training in the morning, playing matches in the afternoon, eating basic food and still having energy left at the end of the day. “Hum toh carbs mein doobe hue hain, (and we were drowning in carbs),” she says.

In fact, one of her first culture shocks came on a plate. “Bread for her meant double roti, the kind you eat only when you’re sick,” says Kashyap. “Abroad, when she realised there were no rotis, she genuinely thought the food was kaccha (raw).” Growing up in Moga, she had never eaten anything boiled or grilled. Salads were alien; cold sandwiches, confusing.

When she returned to India, a switch was flipped. Fitness became a non-negotiable, and a routine had to be followed every day. “When I am on the field, everyone would expect me to be in my best avatar,” she says. “It’s my responsibility to stay fit because I need to set an example for the team. And honestly, I get irritated if I miss my routine.”

Her training has evolved over the years. “Right now, it is more about my cricketing skills,” she says. “After one or two major injuries, I realised that highly physique-centric training can harm me. So now my training is specific, very game-oriented—everything is towards keeping me ready for the match.”

Her metabolism is famously efficient and her nutritionist jokes that she can eat parathas with ghee and still not gain weight. With us, she insists on home-style food. Chicken, roti, sabzi and dal are served; she does not touch the gulab jamun. “She loves only milk cake,” says Kashyap.

If she is in a hotel, Harman asks the chef for the simple, homely version of whatever is available. “She doesn’t understand taste,” says Kashyap. “She only asks, ‘Is this good for the body?’ If yes, she eats it.”

Another culture shock was the foreign accent. In 2016, during her first Women’s Big Bash League stint in Australia, the coach’s words went over her head. It took patience and perseverance to understand him.

She remembers a funny episode on a beach in England. They were playing volleyball, but the ball felt too hard because of the cold. Someone had to let some air out. A young girl from Delhi went up to a passerby, struggling to form a sentence, and finally blurted out, “Ball, air… bye bye?” The man somehow understood, but the team still doesn’t know how!

There are many moments with younger players that have stayed with her, but one, she says, felt almost like looking into a mirror. “Kranti Gaud was telling me how she wanted to play with boys but they wouldn’t let her,” she recalls. “My journey was similar. I would go to the ground but always stand behind the wicketkeeper. They would let me play, but never with them. When I finally got a chance to play, they saw that I could bowl and bat. [Listening to Kranti] felt like she was telling me my own story.”

Sakshi Samant, a 15-year-old district player in Mumbai, said “guts” and “bindaas (carefree) attitude” are what make her a fan of Harman.

What advice does the captain have for aspiring cricketers like Sakshi? “Value time, master one thing at a time, finish what you start, it’s okay to say no, especially when the world keeps asking for more,” she says.

This discipline was built early in life. She remembers returning from her first school nationals, exhausted from a training camp that demanded up to 30 laps of the stadium every day. Until then, cricket for her had been gully matches—five or 10 overs with the boys. Fifty-over cricket was new. She came home and told her mother: “It was very difficult. I’ve never trained like this.”

The following morning, her mother woke her up early and sent her out to run. “Next time, I don’t want to hear that you couldn’t complete training,” she told her. Harman was annoyed then, but would thank her mother later.

Growing up, she was far from the stereotype of the noisy Punjabi child. “I was a quiet backbencher,” she says. Maths was her only subject of interest. After class 10, though, cricket claimed her completely. She joined the Gyan Jyoti School, where Kamaldeep Singh Sodhi changed her life.

Some coaches had seen Harman play before, but they would suggest other sports. “Some said athletics, some said hockey,” she recalls. “But nobody ever said I could be a cricketer. Sodhi sir was the first person who came to me and said, ‘If you want to be a cricketer, I can help you.’ I asked him, ‘Really? There’s a cricket team of women?’ He said there was a national women’s team. I envisioned myself in the national jersey.”

At the time, there was no women’s team at the school, but Sodhi promised he would build one if Harman joined him. So one day, when her father was free, they went to meet the coach. The following morning, she began her training.

As she progressed, Sodhi also stepped in as a life coach. “He gave me examples of cricketers who changed after playing international games,” she says. “He told me, ‘Don’t ever become like that. Stay as you are. Otherwise, there is no difference between them and you.’”

Such gems are aplenty at home, too. Whenever Harman walks in with some leftover aggression from a match, the coaching begins immediately. “Everyone has a feedback,” she says. “Everyone has comments on what I did wrong. And my mother, half amused and half worried, always cuts through the noise with one gentle reminder: ‘Guru Ramdas ji ko yaad kiya karo (keep Guru Ramdas, the fourth Sikh guru, in your heart)’.

When she is struggling, only two people can read her without her having to speak—“My sister and Nupurr,” she says. “Sometimes, people think captains cannot break, but we all break. We just learn how to rebuild quickly.”

Asked about a childhood fear she hasn’t outgrown, Harman pauses for a moment. “During childhood, I always feared talking about or even thinking about anything but cricket,” she says. Studies, marriage and a regular job felt like a threat.

When Kashyap married young and left cricket at 21, Harman, who was travelling for tournaments, couldn’t attend the wedding. But she had a question: “Why so soon? You were meant to do big things. You’re educated, driven… you played, too. Why leave it all for marriage?”

Harman was always scared her family would get her married off, says Kashyap. That was enough reason to play non-stop. “I would see girls doing house chores… but I would play all the time,” she says. “I used to be afraid of losing that freedom. Now that fear isn’t there any more.”

WATCH!

The Harmanpreet Kaur shoot

Looks, fun moments, behind the scenes