April 15, 2019. An evening in Paris.

A Monday mass is underway at the Notre Dame, the cathedral church of the Catholic Archdiocese of Paris. Surrounding the majestic Gothic edifice are scaffoldings; on the ground below lie cigarette butts—workers are in the midst of a major restoration. Inside the limestone walls, the fragrant smoke of incense permeates the cathedral’s spacious nave and aisles, curling up towards the high, vaulted stone ceiling.

A fire alarm goes off. There are no sprinklers on the cathedral’s centuries-old ceilings, but only an elaborate system of perforated tubes that draw in air to detect smoke. In an emergency, help will have to come from outside.

A security guard, only three days into his job and working a double shift because his relief had not arrived, is despatched to investigate. He fails to detect the fire. Amid confusion, nearly half an hour passes before the flames are found.

Too late. By the time the fire brigade arrives, smoke is billowing from the cathedral. Tourists and Parisians watch in disbelief. One of them, Yvette Cooper from Scotland, watches from the banks of the Sienne as the fire gradually engulfs the cathedral and Paris begins to weep. As the spire begins to collapse, she turns away, unable to watch. She calls a friend who lives outside London and says, “Turn on the TV.”

That friend is Barbara Follett. She and her husband have just finished supper, oblivious to the conflagration in Paris. On television, they watch the cathedral burn. “How could a stone structure burn?” they hear journalists asking.

Barbara’s husband, Ken Follett, knows the answer. He had once burnt a cathedral down—the Kingsbridge Cathedral, in his epic novel The Pillars of the Earth. “Everything happened slowly: the beams fell slowly, the arch broke up slowly, and the smashed masonry fell slowly through the air,” Follett wrote, describing the disaster through the eyes of Philip, the prior who governs the fictional cathedral. “Philip was appalled. The sight of such a mighty building being destroyed was strangely shocking. It was like watching a mountain fall down or a river run dry: he had never really thought it could happen.”

Follett knew, unlike most observers, that above the Notre Dame was what builders called “the forest”—a network of massive wooden rafters, each beam cut from oak trees felled centuries ago. “The rafters consist of hundreds of tons of wood, old and very dry,” Follett tweets, answering the journalists’ questions. “When that burns, the roof collapses; then the falling debris destroys the vaulted ceiling, which also falls and destroys the mighty stone pillars that are holding the whole thing up.”

In The Pillars of the Earth, the cathedral’s destruction becomes a turning point: the fire ensures years of labour for a builder and his crew to raise a new one. Much of the plot unfolds during the building of the new cathedral—built not in the traditional, heavy Romanesque style, but in an elaborate new form that comes to be known as Gothic architecture. The burning, in a sense, becomes an act of creation. The novel itself, on the whole, is a metahistory of the destruction and recreation of England in the eleventh century—from the fall of the Anglo-Saxon aristocrats who ruled England for more than 500 years, to the establishment of a new feudal order under the conquering Normans from France.

Because The Pillars of the Earth is among the most widely read novels of all time, and Follett is seen as an authority on cathedrals, his tweet triggers a storm of phone calls from newsrooms. Soon he is giving interviews, explaining what the blaze would likely do to France’s most beloved monument—a place where Napoleon crowned himself emperor, where France celebrated military victories over centuries, and where liberation after World War II was marked. The fall of the spire means the Notre Dame, built not long after the Norman conquest of England as an early and iconic example of Gothic architecture, could be irreparably damaged.

“I spent most of that evening, and all of the following day, doing interviews for radio and television, explaining how the fire might have started and how it would have continued,” Follett tells THE WEEK. “The fire had, by that time, done a lot of damage, although happily the damage was limited.”

It is a Zoom call—five years after the fire—and Follett is in his home in Hertfordshire, near London, with a bookshelf in the background. Apparently, his study. “Each day,” Follett explains. “I come to my chair in this room in the morning, and I write. This is how I have spent my life.”

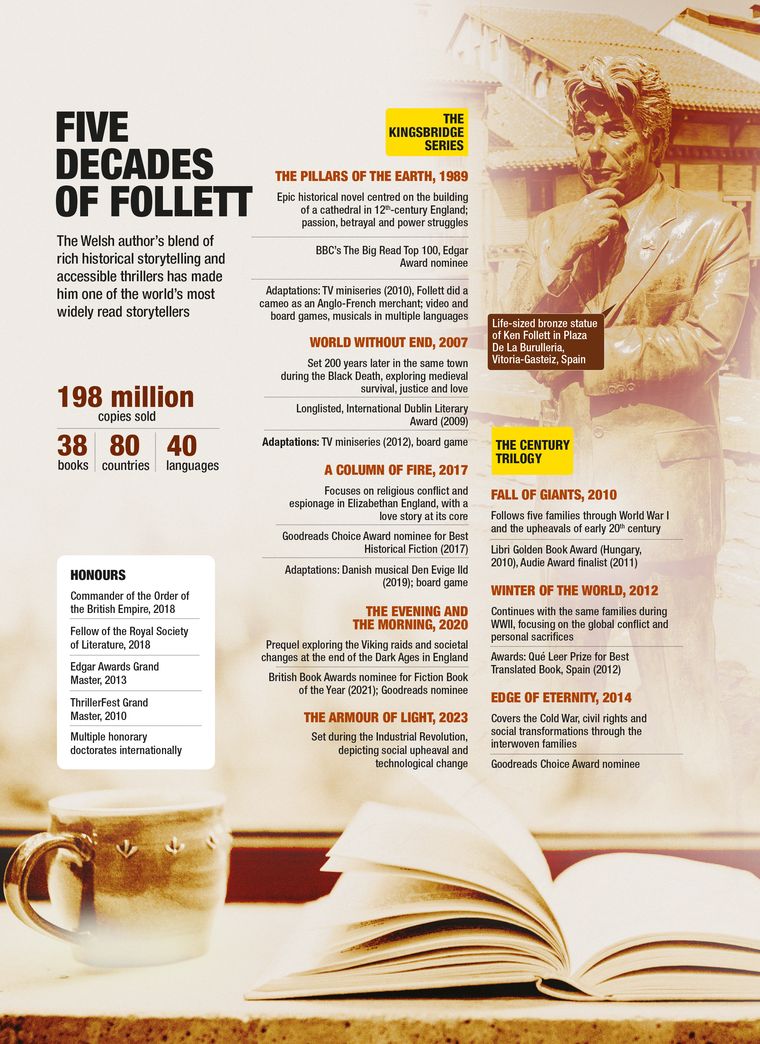

Follett, 76, has written 38 bestsellers—most of them novels—over nearly half a century. His first major success was the Edgar Award-winning Eye of the Needle, a World War II spy thriller published in 1978, when he was 27. Since then, Follett has built his bibliography like a cathedral—stone by stone, book by book—with the patience of someone undertaking monumental work.

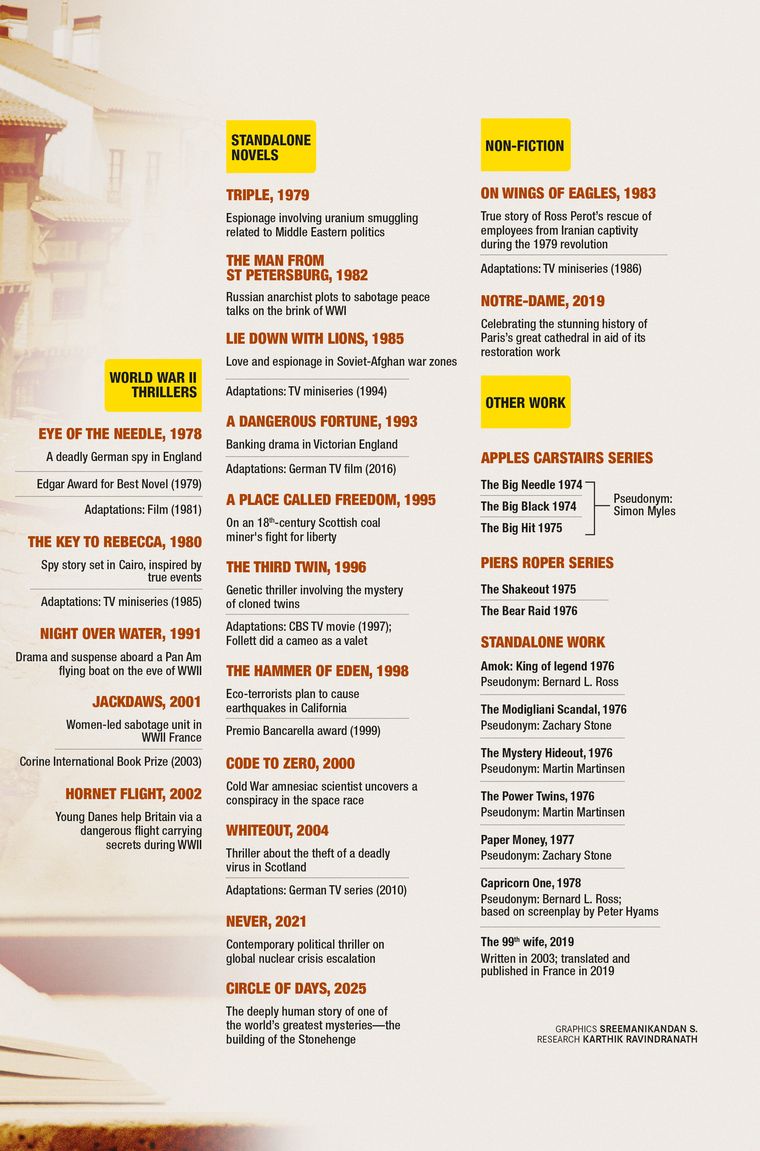

The Kingsbridge series that began with The Pillars of the Earth has evolved into a sweeping five-volume cultural chronicle of mediaeval England. The Century trilogy, which opened with Fall of Giants (2010), has become a panoramic journey through the upheavals of the 20th century. And standalone novels—like Triple (about an Israeli operation in Egypt to steal nuclear fuel), The Man from St Petersburg (a Russian anarchist tries to assassinate a Tsar prince in London), Jackdaws (an all-woman French resistance group taking out a vital German telephone exchange before D-day), Code to Zero (an amnesiac trying to recover his memory to prevent a secret from destroying America’s first satellite launch), and The Third Twin (a researcher unearthing clues to a genetic experiment gone wrong in the US)—have traversed continents and eras.

This room, apparently, is where all these worlds were born. The latest to emerge from it is Circle of Days, an epic about the Neolithic tribes that built Stonehenge, the 5,000-year-old ring of massive standing stones in England. Why Stonehenge was built still remains a matter of debate among historians. It has been interpreted as a sundial, an observatory, a ceremonial site, and a burial ground—possibly it was all of these.

Follett spends months researching before he writes. To prepare, he reads books, studies maps and photographs, uses Google Earth, and travels extensively. “I write an outline of the story and research the background at the same time,” he says. “The two things help one another…. That’s generally the first six months.”

Then comes the first draft, which he shows to family, friends, editors and, of course, historians—so “they can correct errors I have made”. Then he does what most writers would deem unreasonable: he leaves the first draft unedited and writes a completely new one from scratch. “That second draft takes me two to three years,” he says. The first draft, perhaps, is just the scaffolding; the real cathedral must rise from fresh stone, word by word.

Follett’s last release was in 2023—The Armour of Light, the fifth in the Kingsbridge series. The launch of Circle of Days took place at the monument that inspired the quintology—Salisbury Cathedral, the thirteenth-century Gothic marvel whose spire is the tallest in England. Stonehenge is just 12 kilometres from the cathedral.

“Of course, Stonehenge is a religious monument, as Salisbury Cathedral is,” he says. “So they have a lot in common…. In both cases, the actual builders were quite humble people—not rich people, not educated people, not kings and princes.”

Follett hails from Cardiff, Wales. His grandfather was a coal miner; his father, a revenue clerk. “My parents weren’t particularly poor,” he says, “but in the 1950s, when I was a boy, ordinary people in England were not very well off. It was before the prosperity that came with the sixties.”

The family—Follett was the eldest of three children—belonged to a puritanical Christian sect called Plymouth Brethren that preached to its flock to shun television and films. Books were an exception, so Follett devoured as many as he could find. When his demand exceeded what his parents could supply, they took the economical route. “They took me to the public library in Cardiff’s Canton district that looked like a church,” he says. “For me, it was like Christmas.”

From Enid Blyton and Geoffrey Trease, he moved to William Shakespeare. His parents let him read anything he liked, so somewhere along the way, as a teenager, he discovered Ian Fleming’s James Bond. “Everything about Bond is totally contradictory to what Plymouth Brethren believe about life,” Follett says. “He smokes, he drinks, he goes to bed with women who aren’t his wife. He enjoys the high life—champagne, good food, expensive clothes.”

Follett left the puritanical faith to study philosophy at University College London. In 1968, when he was 18, he married his girlfriend Mary Elson, “because we got pregnant”. Mary’s parents were also Plymouth Brethren. Their son, Emanuele, was born the same year; daughter Marie-Claire arrived in 1973.

By then, Follett had become an atheist—though a spiritual one. In the 1970s, as a reporter at the London-based Evening News, he visited a cathedral on the edge of the paper’s circulation area. It was unlike the gospel halls of his childhood, which had nothing but a table in the centre.

“So when I actually saw the cathedral,” he says, “I was really very struck. This was something completely different from the way I had been brought up. It was big, beautiful, highly decorated, expensive, imposing—it was the beginning of my fascination with cathedrals.”

That visit seeded the idea of The Pillars of the Earth.

But first, he had to weather a financial crisis. Leaving journalism, he wrote a novel that earned him a modest advance and bought him time. Then he wrote another, and another, and another still, until he found himself the author of 10 unsuccessful books.

“Each time I wrote a book, I wanted it to be a bestseller,” he says. “So there were 10 disappointments. But all that time, I was learning.”

For his eleventh, he radically changed his writing process. He took an architect’s approach—making a plan of the entire book, listing out characters and chapters, and noting what happens to each. He spent six months just finalising the plan. Then he wrote Eye of the Needle.

The book appeared at a transformative moment in publishing. By the late 1970s, it had become customary to release books in two formats—hardcover (prestigious, costlier) and paperback (cheap, disposable). Each format was handled by different publishers. The hardback deal for Eye of the Needle brought only a few thousand dollars. But the paperback rights went to auction, as publishers sensed it would sell well in shops, supermarkets, airports, and train stations—at least 10 times the hardback numbers. The auction, Follett’s agent told him, had continued till it closed at half a million dollars. Follett had secured his first fortune.

The bestsellers that followed made him a marquee name. Follett also became more politically active. He married Barbara Broer, a rising Labour Party leader who had been married to the South African anti-apartheid activist Richard Turner. Barbara was born in Jamaica, moved to Ethiopia (her father established the country’s first insurance company, with Emperor Haile Selassie as partner), and later to South Africa. She returned to the UK after her marriage with Turner broke down.

In 1985, the year he married Barbara, Follett published Lie Down with the Lions (“terror conspiracies in Paris, guerrilla warfare in Afghanistan,” said publicity material). The next book took unusually longer—four years. It was The Pillars of the Earth.

Follett’s favourite Bond novel is Live and Let Die. Its opening line—“There are moments of great luxury in a secret agent’s life”—could apply to him. He has a taste for fine suits, fast cars and French wine. He never mixes drinking and writing, but he once set Jackdaws in and around Reims, France, just so he could drink champagne and study its cathedral.

“Success has great rewards,” he says. “I live in a very pleasant house, and I drink very good wine and champagne.”

A longtime Labour Party donor, Follett has often been dismissed by Conservative critics as a “champagne socialist”. A BBC anchor once found much amusement during an election broadcast when Follett fumbled and failed to open a bottle of champagne at a Labour Party celebration—perhaps the only time in public that he truly lived up to his surname.

The name Follett is of Norman origin, not Welsh. It means “jester”. The name first appeared in the Domesday Book, the eleventh-century record of England and Wales compiled after the Norman invasion. The Normans, fresh off the victory over the Anglo-Saxon aristocracy, sought to establish a new taxation system. To help record-keeping, people began adopting hereditary surnames.

Perhaps the Norman inheritance explains Follett’s left-reformist leanings. In the 1990s, he became an influential supporter of the New Labour movement led by Tony Blair and Gordon Brown. Barbara, in fact, served as minister of culture and tourism in the Brown cabinet from 2007 to 2010. It was during her tenure that the UK government transformed Stonehenge from a mere historical landmark to a living cultural site.

“When you go to Stonehenge,” Follett says, “you go to the car park, you buy your ticket at the visitor centre, and you take a bus to the monument. When you arrive, you can’t see the visitor centre or the car park. It looks pretty much as it would have looked in the Stone Age. That was Barbara’s concept.”

Surely, she must have also shaped Circle of Days. “Well, she is always interested in what I am writing,” he replies, “but I am the one who writes it.”

Between them, the Folletts have five children and six grandchildren. (Emanuele died in 2018 of leukaemia. “Losing him was completely devastating,” Follett said at the time.)

Barbara has retired from politics, but their social and political connections endure: they are known to make big donations and host extravagant gatherings for friends. One of their closest friends is Yvette Cooper, who had called them when the Notre Dame burnt in 2019. When the Labour Party under Keir Starmer came to power last year, Cooper became home secretary. She now serves as foreign secretary—becoming the first woman in British history to hold both offices.

After the Notre Dame fire, Follett wrote Notre Dame: A Short History of the Meaning of Cathedrals, pledging to donate its proceeds to rebuilding the cathedral. With the reconstruction project attracting more than $1 billion, the proceeds were later reallocated to La Foundation du Patrimoine, an organisation that works to preserve French heritage. The money went to a cathedral in Brittany, France.

Last December, he returned to Paris for the reopening of the Notre Dame as a special guest. “It was a great joy,” he says. “The cathedral looks better than it has ever looked.” The sight, however, was startling. The fire had stripped away centuries of soot from the stones, and the workers had polished them to bring out the true colour. “We thought the stones were grey, because they were grey for hundreds of years,” Follett says. “But in fact, they are white. When they cleaned it, it looked beautiful.”