Diversity will be the hallmark of the new Parliament building. The sanitised environs of Sansad Bhawan are set to resonate with different languages, louder slogans, sharper opinions, and hopefully meaningful debates. Prime Minister Narendra Modi is returning to his post for a third term, and he does so with a new reality and visibly less firepower. He will face an energised opposition led by Rahul Gandhi, and he would have to rely on allies like the Chandrababu Naidu-led Telugu Desam Party and the Nitish Kumar-led Janata Dal (United), who have shaken the BJP-led alliance in the past.

That the BJP fell short of a majority by 32 seats, and of its own target of 370 by 130 seats, means that it would have to change its approach to governance. Early signs are already showing.

At his victory speech on June 4, the poster behind Modi carried a ‘Thank You’ message for the people written in all the official languages, and not just in Hindi as was the practice earlier. This was not a ‘Modi sarkar’, but an NDA one.

This, significantly, ushers in a return to the coalition era of the 1990s, when prime ministers had to rely on allies to govern and use a language of consensus to maintain harmony in Parliament and on the streets. The NDA was formed by Atal Bihari Vajpayee on May 15, 1998, with support from parties and leaders known for their anti-Congress stance. A quarter of a century later, Modi would potentially have to adopt a Vajpayee-like approach to keep his allies close. His party, too, will need to temper its message as it grows in states like Telangana, Andhra Pradesh, Odisha and Kerala.

“We will work with all state governments, including those led by any party,” said Modi. “We will work hard for a Viksit Bharat. This is not the time to stop, but to move forward. The Constitution is our guiding document. We will celebrate the 75 years of the Constitution in a big way this year.”

Modi had transformed himself from an RSS-trained organisation man to a hindutva powerhouse as Gujarat chief minister, only to reorient his image as a statesman with an increased global profile, all the while making a ‘New India’ back home. The challenge now would be to build his image as a consensus builder.

The 2024 mandate has been humbling for some and rewarding for others. There are, however, lessons for all.

For the BJP, which prides itself as the world’s biggest political unit, it is time for change. “What worked in 2019 might not work now,” said a party leader who did not want to be named. “Last time, it did not matter to the voters who the candidate was; they voted for Modi. This time, we continued with the same strategy, which meant many sitting MPs and candidates were complacent and had lost connect with the people. For a voter, local issues matter. If their MPs are inaccessible or ignore basic needs, the voter is bound to rebel at some time. The same was true for our cadre, who felt left out as outsiders were rewarded with tickets.”

Of the 56 turncoats given BJP tickets, only 22 could win.

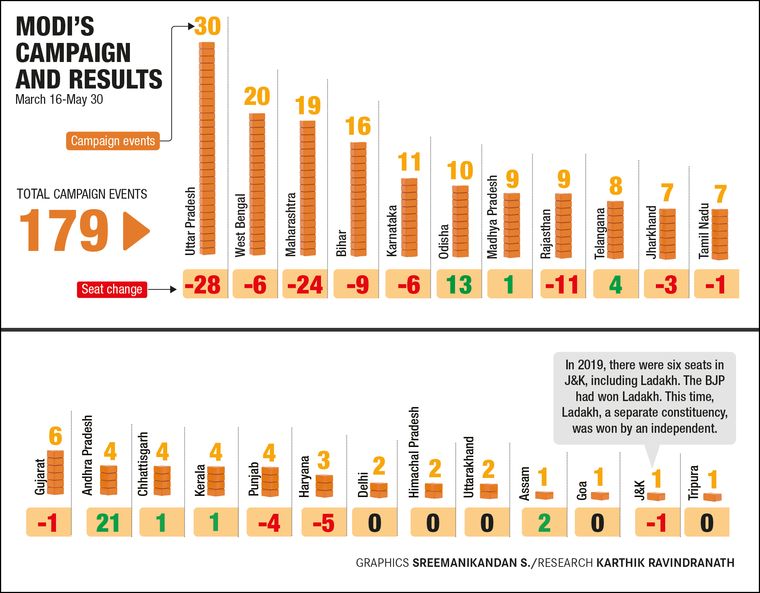

The toughest lesson for the BJP came from the voters of Uttar Pradesh. Despite having Modi and Chief Minister Yogi Adityanath as party generals, the fortress was breached. Modi’s victory margin in Varanasi dropped to 1.5 lakh from 4.8 lakh last time. More notably, the party lost the Faizabad seat, which includes Ayodhya, the temple town where the Ram Mandir stands. The double-engine slogan faltered in the state where the party had, in its mind, ticked all the boxes―pro-hindutva polity, bulldozer politics and social engineering. But, across the state, multiple factors were at play, including lack of jobs, inflation, farmers’ distress, stray cattle, and general fatigue from a 10-year rule. The BJP fell from 71 seats in 2014 to 33 now.

In the heartland states where the BJP experimented by replacing caste groups like Jats and Yadavs with leaders of other castes, there was a comeback of parties that represented the dominant groups’ interests. In Haryana, for instance, this has set the stage for a keen contest in the upcoming assembly elections.

The 2024 mandate has echoes of 2015―the BJP, after an impressive performance in the Lok Sabha elections a year before, lost the Delhi and Bihar assembly polls, forcing it to course correct, improve communication with the cadre, and change its political messaging for the poor and the marginalised. The current Lok Sabha results, which gave 240 seats to the BJP, 63 fewer than in 2019, might propel changes in party organisation and messaging.

Party president J.P. Nadda’s term finishes on June 30, and the BJP might pick a new leader to signal change. Also, the RSS could expand its role; it had pulled back because the party had high numbers and has been winning, mostly, for a decade. The RSS influence could herald changes wherein other leaders, apart from Modi, might see their roles revised. This could create different layers of political leadership, which will be reflected in the new cabinet, party organisation and state leadership.

Those who have observed Modi in the past 24 years―first as Gujarat chief minister and then as prime minister―contend that he is quick to cut his losses and reorient his image. It remains to be seen how he changes his messaging to survive the tumultuous terrain of coalition politics and the numbers game in Parliament, where the focus will be on using the standing committee route to pass legislation and the role of the speaker will be crucial to keep the warring sides in check. In the outgoing Lok Sabha, there was no deputy speaker, a post usually held by other parties. This will now be in demand again.

Coalition politics will also cast a shadow on the BJP’s ideological agenda. It would be tougher to bring in the Uniform Civil Code and ‘one nation, one poll’; instead, there could be more consensual politics, a throwback to the Vajpayee and Manmohan Singh era.

The opposition parties have taken the sheen off Modi. Rahul Gandhi, with his message of protecting the Constitution, would return with a spring in his step to the new Parliament. His single-minded focus on anti-Modism and the promise of a new social order through enhanced reservations and caste census have resonated. The Congress will finally be able to shake off the embarrassment of not having enough seats, 55, to claim the position of leader of opposition. It has 99 now, and is enjoying a perception victory―there is a revival in several states across the south, north, and east, and among its traditional vote banks of dalits and tribals.

Emphasising the party’s role in national politics, Congress president Mallikarjun Kharge said they would keep on fighting to protect the Constitution, and added, significantly, that the party would ensure the proper functioning of Parliament.

The 18th Lok Sabha will have stronger voices, with the Samajwadi Party becoming the third-largest grouping with 37 seats. Even the fourth and fifth positions are held by INDIA allies, the Trinamool Congress and the Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam.

If Mamata Banerjee was able to stave off the BJP challenge in West Bengal, Rashtriya Janata Dal leader Tejashwi Yadav’s spirited fight helped the INDIA bloc win nine seats, improving its tally by eight.

On the western front, the return of Maratha veterans Sharad Pawar and Uddhav Thackeray, along with a good show by the Congress, signalled that the new Lok Sabha would pack a power punch. The breakaway units of the Shiv Sena and the Nationalist Congress Party won fewer seats.

In the next five years, the role of chief ministers will be important as they are set to dictate their agenda to the Centre, and the latter would have no choice but to listen. Nitish and Naidu as NDA allies might help carry messages from their counterparts in other states to the Centre.

The 2024 mandate also indicated that regional satraps leading outfits based on communities and regions would need to fight hard. Intelligent voters are no longer captive if the leaders are seen as complacent or floundering, a lesson the Biju Janata Dal’s Naveen Patnaik and Bahujan Samaj Party head Mayawati have learned the hard way. After 24 years as the unquestioned leader of Odisha, Patnaik walks into the sunset as the BJP wrested the state. It played on Odia pride to target Patnaik’s perceived heir, former IAS officer V.K. Pandian, who is a Tamilian. Mayawati, too, is fading into oblivion as her dedicated cadre switched to the Congress and those who could take on the BJP. Bhim Army chief Chandrashekhar Azad won his maiden election to the Lok Sabha, positioning himself as the heir to the dalit consciousness created by Kanshi Ram.

Also Read

- Congress kept its ear and feet to the ground to script a remarkable resurgence

- Decoding Maharashtra poll verdict: Anger, sympathy and Sharad Pawar’s skilful moves

- How Mamata Banerjee and nephew Abhishek upped the poll game in Bengal

- BJP’s southern push comes a cropper in Tamil Nadu

- Voters have changed, and we have benefited: Suresh Gopi

- Two independents won in Baramulla and Ladakh. What that means for the region?

Diversity will be further reflected in Parliament as the left parties will have eight members―four of the CPI(M), and two each of the CPI and the CPI(ML).

The elections have also thrown up newer entrants, two of whom are jailed―Amritpal Singh from Punjab and Engineer Rashid from Kashmir―who could pose a challenge to mainstream parties. As a serious concern for Punjab, Amritpal, jailed in Assam under the National Security Act, won from Khadoor Sahib seat. Sarabjeet Singh Khalsa, son of Indira Gandhi’s killer Beant Singh, has also been elected as an independent from Faridkot.

Modi put up a brave face after the results, transferring the ‘glory’ of victory from the BJP to the NDA. But, the road to 2029 is likely to be bumpy and uncertain. The country might have clocked impressive GDP numbers, but the government could now be forced to look for the real distress that caused people to think of alternatives. The 2024 budget will provide a clue.

In the new coalition government, where the BJP would have to be conscious of allies’ sensitivities, the role of leaders like Amit Shah, Yogi Adtiyanath, Shivraj Singh Chouhan, Nitin Gadkari and others might be redefined under the RSS’s watchful eyes. The murmurs of a succession plan will only get louder in the years to come.