Zia-ul-Islam, 32, keeps apologising for being hoarse. Like most boys, his voice cracked at 16, but it also became rasp by the scars inflicted in jail, where he was locked up alongside hardened militants in 2008.

It was a summer of mayhem. Zia was 17. “Separatists had called for a 'Muzaffarabad chalo (Let’s go to Muzaffarabad in Pakistan-occupied Kashmir)' agitation against the government’s decision to transfer a part of forest land to the Amarnath Shrine Board. We were told that outsiders were snatching our land in violation of Article 35A of the Constitution. My friends advised me to focus on studies but I joined the protests,” he says. In the middle of the night on August 25, Zia was arrested on charges of stone-pelting and raising pro-Pakistan slogans from his house in Fatehgarh Sheeri in Baramulla.

Zia was one of the first few juveniles to be arrested under the Public Safety Act in Kashmir. A year in prison earned him the tag of a stone-pelter, and every time there was unrest, he was kept in detention for days, sometimes weeks. There were seven cases against him that took 14 years of trials before the court granted him reprieve in 2022.

“I suffered 14 years for a mistake as a teenager,” he says. “I cannot sleep well even today. I dream of being in school and then I wake up shuddering. No one wanted to meet me. My classmates have become professors, police officers and doctors, but I could not fulfil my dream of becoming a lawyer.”

Zia is a panchayati raj institution (PRI) member from Fatehgarh Sheeri, the hotbed of terrorism in Baramulla. He is also the change Kashmir is embracing today, delicately balancing peace and desperately breaking the shackles of violence and cynicism. For thousands like Zia, their cathartic release is no longer throwing stones, but building an edifice of peace in Jammu and Kashmir, brick by brick.

Zia won as an independent candidate in the poll for PRI members in 2018, when the state was under President's rule. “The regional parties had boycotted the panchayat elections,” he says. The three-tier panchayati raj system could be the first step towards grassroot democracy in the valley. After the abrogation of Article 370 in 2019, elections to the block development and district development councils happened for the first time in J&K. “Elections to the panchayats, block development councils and district development councils have been one of the longest pending reforms in J&K,” says Safina Baigh, chairperson of district development council of Baramulla. “Earlier, central funds used to flow into the coffers of MPs and MLAs and never reached the ground. There may be some hiccups today, but as decision-making and fund-flow shifts to the grassroot, more and more people will participate.”

There are many more battles to be won, including the disenchantment that stands in the way of a better future. The conflict has tired out generations. “I don’t have the means to study and become a lawyer,” says Zia. “My life is over, but I want the kids in my village to fulfil their dreams.” He is building classrooms and a library next to the panchayat office in his village. The first set of 150 books arrived on August 20.

Zia learnt English while in jail, reading books given to him by some generous police officers. “My mentor (an officer named Pani) changed my life,” he says. “I met him only for a few minutes, but I will never forget the way he counselled me. He made me think why terror mongers were turning us against our own people.”

Kashmir's children have paid a heavy price for the insurgency. “I have grown up listening to Pakistan radio, reading extremist literature and felt a natural inclination towards the people there,” says Wajahat Farooq Bhat of Sheeri village. “We were taught real life begins after death. Gunshots were given in honour of anyone who died in action. Our joy was not earning college degrees; we fell in love with the idea of death.”

By 2012, stone-pelting had become so commonplace that youngsters graduated to petrol bombs to impress peers. “I remember the first time I threw a stone,” says Wajahat. “It was on a bulletproof vehicle carrying a ballot box in 2014, and the window cracked. I became a hero in my locality.”

When 22-year-old Burhan Wani, the poster boy of Kashmiri separatism, was killed in 2016, many Wajahats were born. Pulwama boys Mohammed Mudasir, 19, and Yawar Mushtaq, 20, who are currently studying BSc (operation theatre technology) in Chandigarh, used to carry stones in their school bags. “We were scared security personnel would come and pick up anyone,” says Mudasir. His father served in the J&K Police. “My father counselled me but I used to go for stone-pelting after returning from school. One day, when I returned home late, my grandmother was waiting with a stick. She said I should kill her first,” he says.

Yawar, son of a small-time businessman, says going to Chandigarh to study was the best decision in their lives. “We could not imagine how children roamed safely at night. We don’t talk about our past to college mates in Chandigarh, but no one is really bothered,” he says.

But it isn’t the same for Kashmiri girls, who are still finding it hard to break from the past. Anika Nazir, 22, of Kupwara battled migraine and depression before she started studying medicine in Srinagar. “I belong to a family where all girls are educated but are not outspoken,” she says. “My brother and I grew up watching the turmoil, even though I did not step out to pelt stones. But I wanted to talk about it.”

Anika joined the NGO Save Youth, Save Future as a volunteer. “I have seen both sides,” she says. “It is wrong to say the youth pelted stones for money. But, at the same time, some of the videos of violence were from Syria and Afghanistan, playing Kashmiri songs in the background and talking about the cruelty of the Indian state.”

When she started using social media to bust fake news, she was branded a traitor. “I think girls are more radicalised than boys,” she says. “I studied in a women's college where they criticised my ideas, my public appearances and my way of dressing. Even my teachers did not support me.” But Anika did not let herself slip into depression; instead, she became a beacon of change. “I have my own YouTube channel and social media accounts, where I spread awareness and pro-India ideas.”

Kashmiris are slowly opening their hearts and minds to new thoughts. Faizan Gul, who runs the Global Youth Foundation in Baramulla, says his parents never voted, just like hundreds of families in the old town of Baramulla. “My parents felt no political party was worth it,” he says. “I haven’t voted till now. But I want to participate in the next polls.” Faizan feels the prevailing peace has nothing to do with the abrogation of Article 370. “I would say the credit goes to security agencies,” he says. “Baramulla used to be a hotbed of militancy in the 1990s and later in 2010 and 2016. Even the police could not enter here, but today it is safe.”

India has seen Punjab vanquishing militancy through the participation of people in development, and easing out the Army after it flushed out militants in the 1980s. It was the combined effort of the local police and the defeat of separatist sympathisers in the assembly elections in 1992 that ended the era of insurgency in the state.

The separatism in J&K may be of a different kind, but the penetration of terror networks in the ecosystem down to the civil society has to be weeded out to establish the rule of law. It is a mammoth task, but the groundwork is being done. When the government was mulling the abrogation of Article 370, National Security Adviser Ajit Doval called in senior J&K police officers and asked if there would be rebellion within the ranks. Many of them expressed concern, but Additional Director General Vijay Kumar told Doval that J&K police had handled militancy at its peak, and it would continue to keep Kashmir safe.

Today, Vijay Kumar is overseeing the quiet transformation of J&K Police’s elite anti-terror unit, Special Operations Group (SOG) or Cargo, equipping it to handle counter-terror operations without the help of other security forces. The elimination of The Resistance Front commander Adil Parray, who had gunned down two cops, was carried out by an SOG squad. In 2022, a Pakistani terrorist was shot by the SOG at the Dargah Hazratbal shrine in Srinagar. “The operation was over in 10 minutes with zero collateral damage,” said Iftikhar Talib, superintendent of police leading Cargo.

A conventional operation, said Vijay Kumar, could have damaged the shrine, resulting in a law and order situation. He said SOG operations were conducted based on inputs generated by the unit itself. This giant leap in becoming self sufficient is facilitated by the training of the SOG by Army’s special para commandos, access to state-of-the-art weapons and the enabling approach of the Central government. The excesses of armed forces personnel and the indiscriminate killings have been a major concern over the years. In contrast, about 60 per cent of the SOG force belongs to Shopian, Baramulla, Srinagar, Anantnag and Bandipora, where militant activities usually take place, and they are careful about the civilians. “When we do an operation in a village, we have family and friends there to whom we are answerable,” said an SOG commando who was part of the team that carried out the Hazratbal operation.

There have been incidents when cops were shot when they returned to their villages, but that has not deterred the youth from joining the police. The SOG has 73 camps across the valley, each consisting 30-40 personnel. It has also set up electronic surveillance units in every district and joint interrogation centres to synergise activities with other security forces operating in the valley.

According to R.R. Swain, additional director general of police (CID), the three-decade-long debilitation of the system will take time to repair, and it may take longer to restore the trust and confidence of the people. “Everyone in J&K has been made to balance between the Indian state and the Pakistani state,” he says. “Today, universities, colleges, schools, financial bodies and the vast network of religious institutions are approaching us saying that they were fed up of having a gun to their head and told what to do.”

Swain is optimistic. “Unlike the neighbour, the biggest weapon the Indian state has is the rule of law,” he says. “We believe that it is this very law, which [the Pakistan-backed forces] have subverted, that will restore life into each one of these institutions.”

The biggest institution is the state government itself, comprising the babus, policy makers and file-movers sitting in the secretariat in Srinagar. Before 2019, the corridors were so full of middlemen and power brokers that it was impossible to wade through them. The outcome was stalled development projects, corruption and nepotism. “I don’t know if people recognised the level of degradation,” says a government official who did not wish to be named. “The employees engaged through backdoor exceeded 2.5 lakh.” To make matters worse, the absence of a transparent financial system channelled the money to the wrong hands.

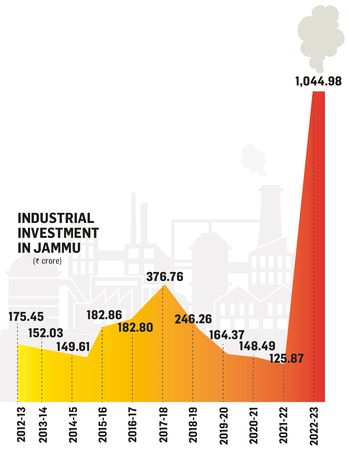

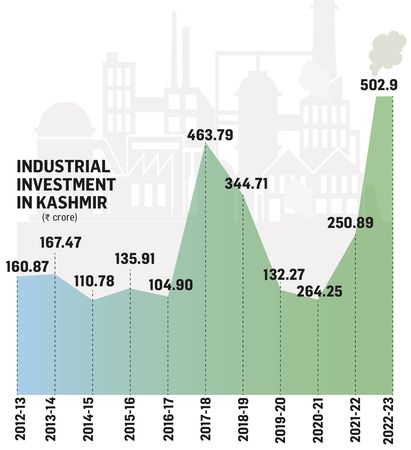

“One significant change post abrogation of Article 370 is transparency in government expenditure, functioning of the Jammu and Kashmir Bank and a strict watch on the movement of files in the secretariat,” says chief secretary Arun Mehta. The government has dismissed 52 persons in key government positions under Article 311 for anti-national activity and 67 bureaucrats for nonperformance. In 2021, two sons of Syed Salahuddin, PoK-based head of Hizbul Mujahideen, were dismissed from service for alleged involvement in terror-funding activities.

“We are trying to make the system accountable,” says Mehta. “All government officials have to file an e-property return and their annual confidential reports online.” To weed out corruption, the process of e-tendering of projects has begun. “The beauty of an e-office is that you cannot destroy records and delays can be tracked,” he says.

The changes happening in Srinagar may take time to reach the rest of J&K. Efforts are on to bridge the disconnect between the capital and the far-off areas, like building road connectivity to all villages of at least 250 people. Ghulam Hasan, sarpanch of Khiram village in Anantnag district, has witnessed three transitions taken place in the valley since 1950. “When I was born, there was neither militancy nor development,” he says. “We lived in the lap of nature but gradually terrorism gained foot in the region and we got caught between security forces and militants. Now people want the villages to be connected by road.” The road from Khiram to Achdhar, where Hasan lives, ends at a primary school. But there is no tap water and the nearby springs remain the main sources.

Also read

- CID DG R.R. Swain: Valley’s own commando

- PWD Principal secretary Shailendra Kumar: Paving road to peace

- Athar Aamir Khan, commissioner, Srinagar Municipal Corporation: Keeping Kashmir smart

- J&K Sports Council secretary Nuzhat Gull: The people's champion

- IT secretary Prerna Puri: Transforming with technology

- ADGP Vijay Kumar: Catching merchants of death

Gulam Ahmed Rather, who has been teaching in the school for 20 years, commutes several kilometres on his scooter every day. He points out that while the road has been built, there is no transport. “Locals are pooling in resources to create transport facility for emergencies,” says Dr Shazia Manzoor, professor at Kashmir University, who led the socioeconomic impact survey of the Pradhan Mantri Gram Sadak Yojana.

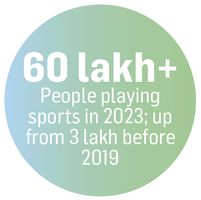

The most visible change in Kashmir is perhaps boys and girls swarming playgrounds in brightly lit stadiums in remote districts. Ulfat Bano, 28, a football coach from Budgam, is one of the few people who created the trend of women football players wearing the hijab. It is fast picking up, as girls everywhere are getting into the field. “I was 16 when I started playing sports, but I always wanted to play outdoor games in my village,” says Ulfat. “Later, when I started coaching girls, many of them came up to me saying they want to play outdoor games like football. In 2013, I worked upon the idea with five friends to play football wearing the hijab.”

Today, 85 of Ulfat's 350 pupils are girls. “The boys are from downtown or other conflict zones. Some were addicted to drugs. Now they are playing sports. For girls, we did not want to change the culture by making them give up the hijab,” says Ulfat.

Tariq Nazir, 26, another trainer, says some 220 women across the valley are playing football wearing the hijab―200 in six Khelo India centres and 20 in three private football clubs. Now schools have also taken up the sport. Nuzhat Gull, the first woman secretary of the Jammu & Kashmir Sports Council, helped Ulfat take the idea forward in an organised way. “From the grounds in my village where I played football wearing the hijab, it is a dream come true to see Kashmiri girls in open stadiums playing football,” says Ulfat. The playground is clearly getting bigger in Kashmir.