We are in August 1980, in the pleasant, middle-class Buenos Aires neighborhood of La Paternal. No. 2257, Lascano Street is a plain style house of predictable form, flat wall on one edge of the sidewalk.

In the neighborhood is the home ground of Argentinos Juniors, Diego Maradona’s first club. “The club grounds are very small; there is just a brick wall on one end,” recalls Rex Gowar, who followed the legend's career as a journalist from close quarters. “He lights the place up whenever he plays. It is a small club with no real claim to fame other than having discovered him. Later, on the Maradona transfer money, they built themselves a much better club.”

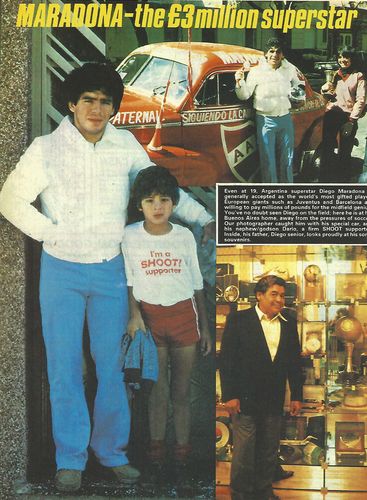

Outside the club, a fan has an old car painted in the team colours, predominantly red with some white. “The car even has a telephone―don’t know if it is working. I take a picture of Maradona holding the receiver to his mouth, with the wire coming out of the car,” recalls Gowar.

Back to the house.

La Paternal is an unpretentious barrio, named after an insurance company that built working-class homes at the turn of the century. The house is two-toned, speckled magenta rising about waist-high, an almost-white faded yellow, also speckled, on top; two windows on the sides, a narrow door in the centre, burglar bars with a simple geometric design protecting the windows and door, all on a row of houses joined together by their side walls.

“It is a fairly standard kind of colonial style arrangement, built on specific measurement, about eight-and-a-half metres wide in a kind of street where lots of houses are sort of similar,” says Gowar. “Inside, it is rectangular and goes quite deep into the block. Past the front door is an open hall with a table where visiting people sit, then a kitchen, and a long hallway with rooms off it.”

It is Maradona's first house, one that helped the family get out of the shanty town called Villa Fiorito, the poor, hardscrabble barrio of dirt streets and mud puddles, street hawkers, day labourers and blue-collar workers, where he was born in November 1960.

In the living area of the house, Gowar surveys the trophy cabinet. “He already had a pretty impressive collection, thanks to youth tournaments won with Argentinos Juniors, with the kids' team of Argentinos Juniors called Las Cebollitas, the Little Onions,” he says.

Maradona is just 19, and Gowar is standing on the edge between two periods of the legend’s life.

In his life, Maradona has been called 'El Diez', 'El Pibe de Oro', or simply 'El Pibe'―'The Kid'―but when he was 13, he was the ace of Las Cebollitas and his nickname was 'El Peluza'―'The Teddy', for his fuzzy hair. He is said to have cried when he missed a chance in the team’s lone loss in 136 games. As the legend goes, the opposing coach, as a way of consolation, said to him: “Don’t cry, little brother, you will be the best in the world.”

The page that was never printed: Gowar interviewed Maradona at a time when major European clubs were showing interest; this page of the publication SHOOT! shows a young Maradona with his nephew Dario, near a special car in Argentinos colours with a telephone inside, and his father, Diego senior, at their home. A printers' strike meant that the story was never published | courtesy Rex Gowar

The page that was never printed: Gowar interviewed Maradona at a time when major European clubs were showing interest; this page of the publication SHOOT! shows a young Maradona with his nephew Dario, near a special car in Argentinos colours with a telephone inside, and his father, Diego senior, at their home. A printers' strike meant that the story was never published | courtesy Rex Gowar

Gowar was at the time working for SHOOT!, an English publication that no longer exists. Due to a printers’ strike, the interview he did with the 19-year-old was never published.

Besides SHOOT!, Gowar worked for the Buenos Aires Herald and then for Reuters in Buenos Aires, London and Rome at times that coincided with the career of Maradona in Europe. “I was always close by,” says Gowar.

Gowar’s impressions of the young Maradona were that he was “a fairly normal Argentine teenager of working-class origin”. A few years later, when he was at Boca Juniors, before going to Barcelona, “he was very popular, though there were people who criticised him for being arrogant”.

Maradona was exceptional as a young player. “Once Boca goalkeeper Hugo Gatti taunted him for being overweight before a game,” recalls Gowar. “So, Maradona said 'I am going to put 3 goals past him', and ended up putting four. One of them was a free kick almost from the corner flag that went cold right in the top far corner. He was just as good as his word.” This was 1979, and Maradona was just 18.

By the time Gowar interviewed Maradona, he had already won the 1979 World Youth Cup in Japan, and the journalist asked him what the win meant to him. “It’s the biggest thing in my life because I had never won a championship like that as a professional,” responded Maradona. “And to show what Argentine football is like with all the other teams in the world and beat them well, not with ease but with clarity, showing what Argentine football has with its passing game, rotating and reaching the goal.”

Maradona went on to win the Argentine first division championship with Boca in 1981. La Paternal and Villa Fiorito are today places of pilgrimage for millions of Maradona fans from around the world.

Maradona started to be compared with Pelé at about the time of the interview, says Gowar. In the 1970 World Cup, Pelé did a dummy on the Uruguay goalkeeper. “The ball was coming from the left and Pelé was running towards it. The goalkeeper came out and Pelé just ran over the ball and past the goalkeeper, who was totally flummoxed. He then swivelled and kicked the ball, which went just outside. Maradona did the same thing to Fiori in a league game in 1979,” recalls Gowar. “The footwork was the principal thing. Maradona was very nimble, though he was more heavily built than Messi. He could somehow retain balance when he was put off balance by defenders trying to bring him down. It was just incredible.”

Mexico 1986 built Maradona the legend. The game against England was the first time Argentina confronted the British after the Falklands War. Tensions were so high that tanks of the Mexican military patrolled the streets around Estadio Azteca. Police were deployed in the stands.

The match is remembered for Maradona's two goals that sunk England. The first one the controversial 'Hand of God' goal, and the second, an out-of-this-world solo effort that has been described as one of the greatest in football history. Gowar says he did not actually see the first goal. “It all happened so quickly,” he says. The second one was pure magic. “What I remember is him suddenly launching a run, and at each stage thinking where it looked like an England player may manage to stop him, and he got past him... and then he did that sidestep when he dragged the ball across in front of goalie, and pushed it in.”

Post the game, in the locker room, Argentine reporters asked Maradona whether that first goal had been with the help of his hand. “He reacted like a typical Argentine or South American,” recalls Gowar, who was in another section of the locker room but had Maradona’s words related to him by an Argentine colleague. “In a manner of saying thanks to God, he said: ‘Well, it was a bit with the head of Maradona and a bit with the hand of God.’ This is what an Argentine kid with that kind of background would say, thanks to God, thanks for His help, as in something that did not involve cheating.” Maradona, like the majority of Argentinians, was a Catholic.

Also read

- Future's bright for World Cup winners Argentina. Here's why

- Story of FIFA World Cup 2022 in 10 photos

- These two clubs had players in every World Cup final since 1982

- Qatar 2022: Antonio Lahoz, the referee who Messi confronted, sent home

- Qatar 2022: Adidas reveals 'Al Hilm', official match ball for FIFA World Cup finals

- Qatar World Cup: Four unsung heroes and why they are vital to their teams

The beauty of the quote was acquired later, with so much talk and writing about it, says Gowar, whose report for Reuters about the quip went viral. “Some people would think that the statement was just as cheeky as the way he scored that goal,” says Gowar. “The quote had a great reaction in Argentina, a terrible reaction in England. I am amazed by how much the English have come around to living with it.”

Maradona, says Gowar, was very good at free kicks, and that is one thing Messi learnt from him when the former coached the national side. Maradona had a tragic end to his World Cup career, when he got suspended after two matches in USA 1994. “He scored a good goal against Greece,” says Gowar. “But it was his understanding with Caniggia that really showed him as a leader. They were losing 2-1 to Nigeria when Caniggia scored two goals., one of which started with a free kick taken by Maradona."

Gowar attributes Maradona’s greatness to “his speed of thought”. He was very quick to read the situation and make a run or a pass. “The difference between Messi and Maradona is that Messi has managed to do it day in and day out, every weekend,” notes Gowar. “Maradona had spells, whether playing for Argentina or not. Maradona had it all and yet, some would say, he didn’t have a right foot, or he didn’t use his head all that much, that Pelé was more complete. The genius of Maradona was that he was a step ahead of everybody on the football field, in his head, and execution.”