A raging pandemic and an economic slowdown had hit the people hard. The loss of livelihood had particularly squeezed the middle class and the poor. And the election was their opportunity to express their opinion.

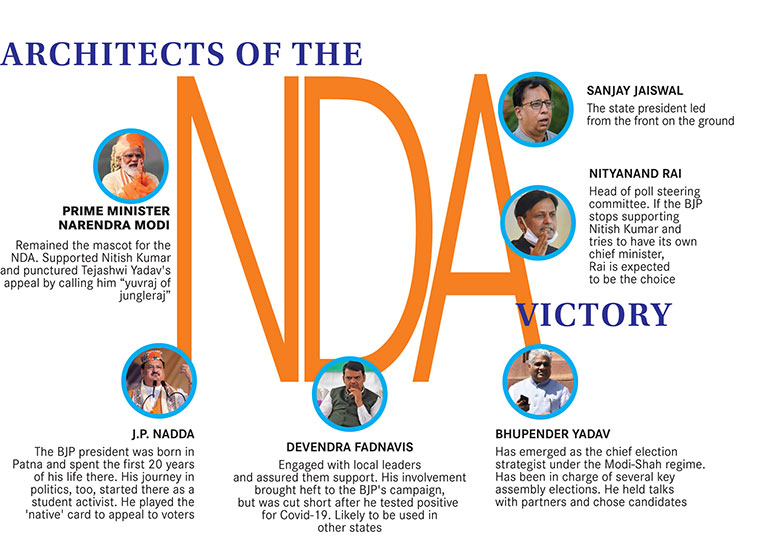

When the votes were counted on November 10, it was clear that they had largely reposed their faith in the ruling dispensation, not just in Bihar, but also in eight other states where bypolls were held in the 59 assembly seats and one Lok Sabha constituency. The BJP retained its edge over the rivals. Prime Minister Narendra Modi, in particular, saved the day for the National Democratic Alliance in Bihar.

The saffron party, which had suffered several setbacks in states since 2018, has regained some of the lost ground in the assembly polls. It won 41 of these 59 assembly byelections, mostly at the cost of the Congress. The Shivraj Singh Chouhan government in Madhya Pradesh is now in comfortable position (out of 28 seats that went to the polls, the BJP won 19). In Gujarat, the party won all the eight seats. It won six out of seven seats in Uttar Pradesh and five in Manipur. The victory in the Dubbaka constituency in Telangana has provided the party with a crucial entry into the state.

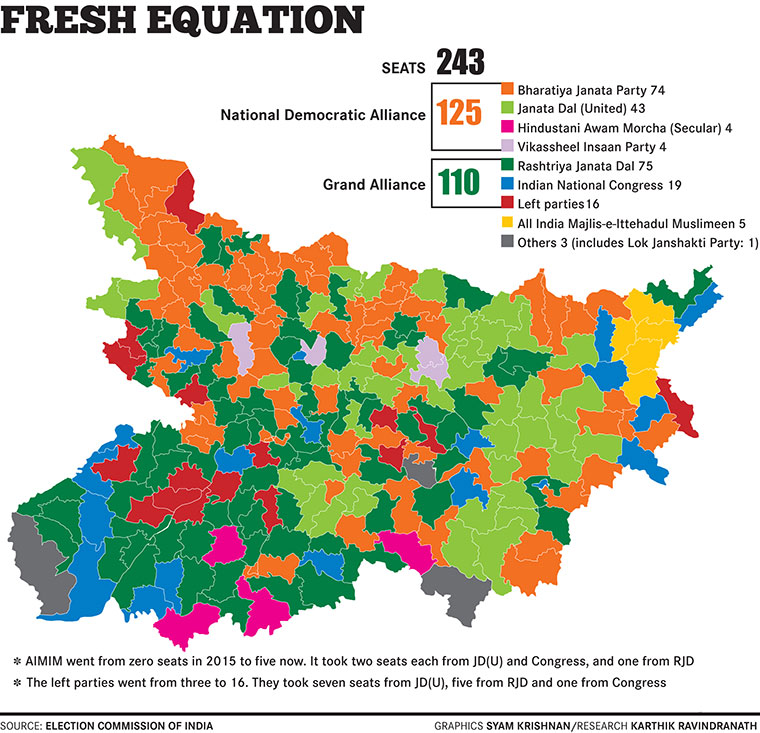

In Bihar, the BJP emerged as the dominant player, winning 74 seats, 21 more than what it won five years ago. For the first time, it is within striking distance of having its own chief minister in the state. For now, the BJP has said Nitish Kumar would continue as chief minister as it had promised before the elections.

The Bihar story, however, is far from a linear one. Nitish’s diminished appeal (his Janata Dal (U)’s tally is down by 28 seats) has opened the doors for Tejashwi Yadav, whose Rashtriya Janata Dal is the single-largest party with 75 seats. The RJD bettered its vote share from 18.3 per cent in 2015 to 23.1 per cent, polling nearly 18 lakh more votes than 2015. The BJP dropped from 24.4 per cent to 19.5 per cent, polling 11 lakh fewer votes. Surprisingly, the JD(U) polled almost the same number of votes as 2015.

The good show by Hyderabad MP Asaduddin Owaisi’s All India Majlis-e-Ittehadul Muslimeen and the left parties has created a new dynamic in the state. The main takeaway for the opposition parties to counter the BJP is to keep the issues local and find a narrative that takes the attention away from national issues.

Nitish has just managed to survive. “It was an attempt by some of our people, and some rivals to harm Nitish Kumar,” said K.C. Tyagi, senior JD(U) leader and a close associate of Nitish. Chirag Paswan’s Lok Janshakti Party played a crucial role in ensuring an upper hand for the BJP. The LJP, which was part of the NDA, had put up candidates in 143 seats against the JD(U) and in five seats against the BJP. The LJP is said to have hurt the JD(U) in some 30 seats, even though it could win only one seat and 5.6 per cent of votes.

Despite never having a majority of his own, Nitish survived the rough Bihar politics through careful manoeuvring. He needed the help of the BJP or the RJD to be in power. He had a brush with propriety in 2005, when his alliance did not have the numbers. During a meeting of some leaders at fellow socialist and party man George Fernandes's house, a suggestion was made that money be arranged to win over legislators. Nitish refused to be part of it. In 2014, he took the moral responsibility of his party’s disastrous defeat in the Lok Sabha elections and resigned from the post of the chief minister. He will be closely watched this time, too.

The BJP will pose a challenge during the distribution of portfolios, and might want them to be divided proportionally to the number of seats. A lot will depend on how Nitish plays his cards to wriggle out of the tight situation. The buzz in Patna is that he would be offered a position in Delhi, so that the BJP can have its chief minister—either a cabinet berth or the post of the vice president when the slot opens up in 2022. A bigger challenge, however, would be saving his socialist legacy.

Beyond the political machinations, the election results mark a subtle break from the past. The elections were dominated by real issues, rather than caste or religion. The BJP crafted its strategy accordingly.

On October 23, Modi addressed three rallies in the state where he focused on the national issues, ranging from the Galwan clash to the removal of Article 370, to turn around the campaign. However, as Tejashwi's promise of signing the first cabinet order for filling 10 lakh government jobs gained traction, the BJP shifted its strategy in the second phase of polling. The result was visible—the grand alliance cornered most of the seats in phase 1, but lost steam in the later ones.

Modi masterfully coined the term jungleraj ke yuvraj, which linked Tejashwi to his father's rule, before phase 2. Tejashwi had carefully omitted Lalu Prasad from the publicity posters. BJP sources said phase 2 witnessed the BJP picking up steam and bettering its strike rate.

During the third phase, when the elections covered the Seemanchal, Mithila and Kosi region, which has significant Muslim presence, the BJP talked about the Ram Temple. Even Modi referred to those people who refused to chant Bharat Mata ki Jai or Jai Shri Ram. The BJP bettered its score here as reverse polarisation and Owaisi's AIMIM splitting the Muslim votes helped the party. The AIMIM won five seats and caused visible damage to the RJD and the Congress that usually get a majority of Muslim votes.

Despite the region-wise nuancing of campaign speeches, the overall narrative of the NDA focused on the work done by the Centre and Nitish in the past 15 years. “The people have reposed faith in the leadership capabilities of Nitish Kumar and Narendra Modi. People have seen the good work done by them. The election campaign has been very constructive and positive. Political parties who used to polarise and divide parties in the form of caste and religion had started talking about politics of performance by focusing on issues and presenting report cards,” said Dr Guru Prakash Paswan, the BJP's national spokesperson and assistant professor at Patna University.

Interestingly, it was the RJD-led grand alliance which kept the campaign focused on the local issues, particularly the lack of jobs in the state. “The RJD came to the first position as people, too, were focussed on the issues despite all the misinformation. The prime minister used the words jungleraj and yuvraj of jungleraj, and even Nitish Kumar made personal comments. Yet people voted for the RJD,” said Dr Nawal Kishore, associate professor at Delhi University and RJD spokesperson.

Tejashwi's ‘issue-based’ narrative saw huge crowds flocking to his rallies. The exit polls gave a thumbs up to the grand alliance, but only to find that psephologists had got it wrong once again.

The difference, apparently, was the silent voters who were not captured in the data. Modi was the first to publicly acknowledge their contribution as he announced victory for the NDA even before the Election Commission did. “Bihar has again taught the first lesson of the democracy to the world. The poor, marginalised and women have voted in record numbers,” the prime minister tweeted. In this message lies the crux of the NDA victory, and how Nitish held. The vote bank of women and the extremely backward castes (EBC), which Nitish had created in the past 15 years through welfare and policy interventions, kept its faith in him.

Tejashwi's rallies attracted young men, but women and girls were missing. “The exit polls created an anxiety among people, especially women, as they asked if the same old rule of 15 years will return,” said Guru Prakash. Even Tejashwi's speech in one of the rallies referring to the Lalu tenure where babus were afraid of the poor revived the fear among the upper castes.

The upper castes and the Yadavs have always held power in the state, and the EBCs existed at the margins. It was only after Nitish gave them greater representation that they chose to stay with him. They make a quarter of the population, and the RJD's promise of job creation was to take the focus off the Yadav-dominated politics and bring this section to its side. But they seem to have sided with the NDA.

The new government is likely to focus on a faster roll-out of development plans as a much aggressive opposition will be watching it. The state's aspirational population has chosen two big players in these elections, the BJP and Tejashwi. By diminishing Nitish, Bihar is taking a break from Mandal politics that started in the 1990s. The shift has just started, and the BJP will depend on Modi’s popularity to accelerate it.