The Aam Aadmi Party recently felicitated a group of senior citizens, beneficiaries of the Delhi government’s free pilgrimage scheme. The group, just back from the Jagannath Temple in Puri, was in for a surprise as Chief Minister Arvind Kejriwal dropped in to talk to them. Hands folded, a smile on his face, Kejriwal inquired about their well-being and the trip, and sought their blessings. The elders wished that a tour to Rameswaram be organised next, and Kejriwal, called ‘Shravan Kumar’ by some in the group, readily agreed.

If he came across as a ‘dutiful son’ in the meeting with the elders, he was the empathetic ‘elder brother’ as he shared a bus ride with women after his government made travel in public buses free for them. Elsewhere, he was a ‘favourite uncle’ as he spoke to students and parents at a recent mega parent-teacher meeting held in state government schools.

There is a world of difference between the Kejriwal of 2020 and his ‘muffler man’ avatar of 2013, when the fledgling AAP had made a stunning debut with 28 seats in the state elections. The muffler had come to symbolise the aam aadmi fighting a corrupt establishment, but it has vanished since. Kejriwal even quipped recently that people had failed to notice its absence.

No longer the rebel, he is now the family man who understands the problems of the common man. An empathetic smile has replaced the intense stare of a rebel, and pictures showing him doing mundane activities—checking potted plants for mosquito larvae or doing puja with his wife, Sunita—are often seen on his and his party’s social media pages.

Full-page newspaper ads and billboards have further affirmed this new avatar. And though political rivals may call it a waste of public money, the ads were an important tool in the visual transformation of Kejriwal.

It terms of content, too, the Kejriwal of today is far removed from the man who accused the Centre of creating hurdles and even claimed that Prime Minister Narendra Modi could get him bumped off.

Of late, Kejriwal has desisted from attacking Modi and the Centre, and his party has strategically been on the Centre’s side in issues such as the abrogation of Article 370 and the Ayodhya verdict.

Recently, referring to Home Minister Amit Shah’s attacks on him, Kejriwal told reporters: “I accept his abuses. But I will not abuse him back. I do not want to indulge in politics of abuse.”

The change of tack, according to AAP leaders, is because the people in Delhi did not want their government to constantly blame the Centre for everything. Also, it was done to counter the image of a dictator and a hothead, which his friends-turned-foes had created.

If the leader has changed, so has the party. The AAP has decided to go totally local and keep the focus on its schools, clinics and subsidies, including free water and electricity up to 20,000 litres and 200 units.

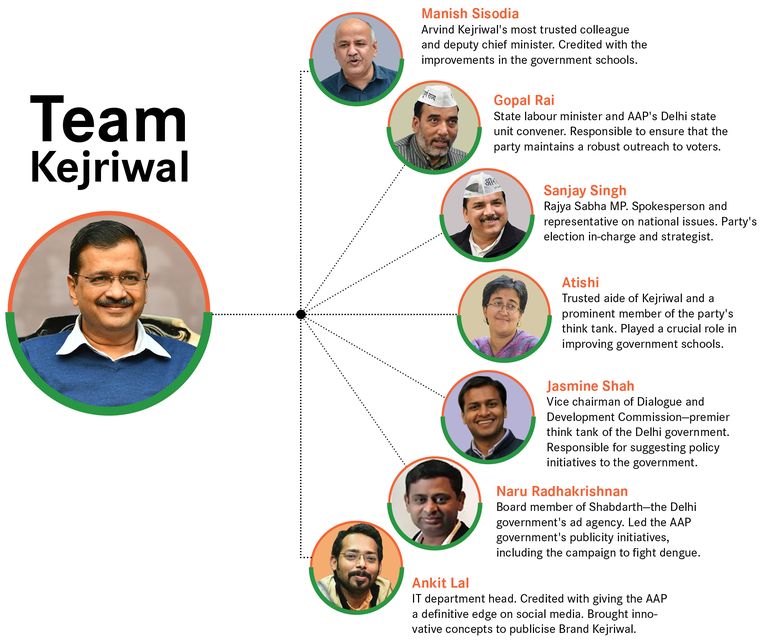

“For the first time, there is a government that has done more than it had promised,” said AAP’s Delhi convener Gopal Rai. “The government has acted as a friend in dealing with the problems of the common man.”

The stakes are high for the AAP, which had won a mammoth 67 of 70 seats in 2015, but has not tasted much electoral success after that. It failed to make an impact in the 2017 municipal elections, and its forays outside Delhi have been disappointing. Just a few months ago, in the Lok Sabha elections, it failed to win a single seat in Delhi, coming third in six of the seven constituencies.

The party, however, quickly put aside the loss and put its national ambitions on the back-burner. It promptly launched the slogan ‘Dilli Mein Toh Kejriwal (In Delhi, it’s Kejriwal)’, which seems to have gathered steam, especially with the recent electoral setbacks for the BJP in several states.

“The Lok Sabha election was for forming government at the Centre, in which we could not have played a big role,” said Rai. “The Vidhan Sabha election is to form a government in Delhi, where we are a key [party].”

Currently, the AAP seems to be the frontrunner in the February 8 elections, largely because other parties do not have a chief minister candidate to challenge Kejriwal. Also, the AAP has kept a tight grip on its core vote bank of the lower middle-class and underprivileged sections, the migrant population and the residents of unauthorised colonies.

The party’s campaign is focused on projecting the fact that the government’s schemes have helped people in a time of economic distress. “Especially now, every few thousand rupees that gets added to your monthly savings is not insubstantial,” said AAP leader Atishi.

The AAP has asked people to draw a comparison between the two models of governance in Delhi; one under the AAP, the other under the BJP-controlled municipal corporations and the Delhi Police.

The party will also rely on the tested door-to-door campaign. It has already reached 35 lakh households in the first round, and has distributed a report card of the government’s performance. The second round will involve publicising the party’s manifesto for the coming five years.

Kejriwal continues to be the party’s prime vote catcher. And armed with a new slogan—’Acchhe Beete Paanch Saal, Lage Raho Kejriwal (The five years went well, carry on Kejriwal)’—the man is expected to be the AAP’s lead campaigner. But before that happens, his town hall meetings, where he has taken questions from the public, have been carefully curated and telecast live in a bid to reach out to all sections of society.

The AAP’s intent is made clear by its decision to rope in strategist Prashant Kishor and his organisation, I-PAC. The door-to-door outreach, the meticulously planned town halls and the leader-centric slogans were classic Kishor.

The AAP is also relying on its 1.3 lakh volunteers reaching out to voters, a strategy that had worked wonders in 2013 and 2015. As many as 50 volunteers would be deputed per booth during the campaign, while 10 would be assigned to every booth during polling.

Crowd-sourcing, said party leaders, would be the main source of money, and fundraising dinners, and lunch and tea parties, are being organised; the party raised 01.5 crore at a recent dinner.

Moreover, Deputy Chief Minister Manish Sisodia’s online campaign got Rs28 lakh in two days.

Perhaps more importantly, amid the debate on and protests against the Citizenship (Amendment) Act and the proposed National Register of Indian Citizens—under whose shadow the election is taking place—the AAP has been taking a cautious approach. Wary of the BJP polarising the election, the party has described the amendment as something that will affect every Indian, not just Muslims, and especially the poor. It has also viewed the police action in Jamia Millia Islamia and Jawaharlal Nehru University as a law-and-order problem, and hence as a failure of the Centre-controlled Delhi Police. This, however, has angered liberals, who expected Kejriwal, one of the faces of the anti-corruption movement of 2011, to stand with the protestors.

But Kejriwal has been careful not to fall into the BJP’s nationalism trap, and his criticism has been based on why the Modi government was going ahead with such measures when the focus ought to be on economic issues. The AAP had voted against the CAA in Parliament.

“The BJP is the real tukde-tukde gang, which through the vile CAA is trying to divide the society on communal lines and has unleashed the violence witnessed on the streets of Delhi,” said AAP’s Rajya Sabha member Sanjay Singh, who is also election in-charge for Delhi.

The AAP also believes that the BJP’s emphasis on CAA-NRIC could backfire, especially as the city’s migrant population is concerned about how the amendment would impact them. They have seen what had happened in Assam, where lakhs of Hindus, a large number of them migrants from other states, were left out of the NRC.

But the BJP, perceived to be the AAP’s main rival in these elections, is desperate to win Delhi, which it has ruled only once—22 years ago. It is hoping to build on the Lok Sabha election victory, where it had won all seven seats.

But, in the wake of diminishing returns for the nationalist agenda in recent state elections, the BJP is trying to focus on the “failures” of the AAP regime. It has launched a campaign called ‘Paanch Saal Jhooth Aur Bawal (Five years of lies and chaos)’, and is telling people that it would be better to have one party at the municipal, state and national levels.

Party working president J.P. Nadda has personally been focusing on booth-level management in every constituency, and some AAP leaders admit that they are wary of the BJP’s election machinery.

Also read

- Delhi Assembly: AAP chooses Atishi as opposition leader, becomes first woman to hold the post

- Rekha Gupta sworn in as Delhi CM, meet the new cabinet

- Delhi Assembly Poll Results 2025: Failed in ‘Agni Pariksha’? BJP’s Parvesh Verma defeats AAP supremo Arvind Kejriwal

- BJP waived off debt worth Rs 10 lakh crore of its corporate ‘friends’, AAP spending on people: Kejriwal

- Amid Delhi Assembly polls, Pakistani Hindu refugees live between hope and hardship

- Delhi Assembly polls: Kejriwal promises free power, water schemes for tenants; police stop screening of AAP documentary

The party has also promised greater subsidies to counter the AAP’s claim that it would cut subsidies if voted to power. “We will only provide more,” said Delhi BJP president Manoj Tiwari. “Whatever the people have received in the past five years through subsidies, in terms of savings made, we will provide five times more than that in the next five years.”

The BJP is trying to counter the AAP’s reach in unauthorised colonies by granting the residents ownership rights. It has also attacked the AAP for not launching the Centre’s Ayushman Bharat scheme in Delhi.

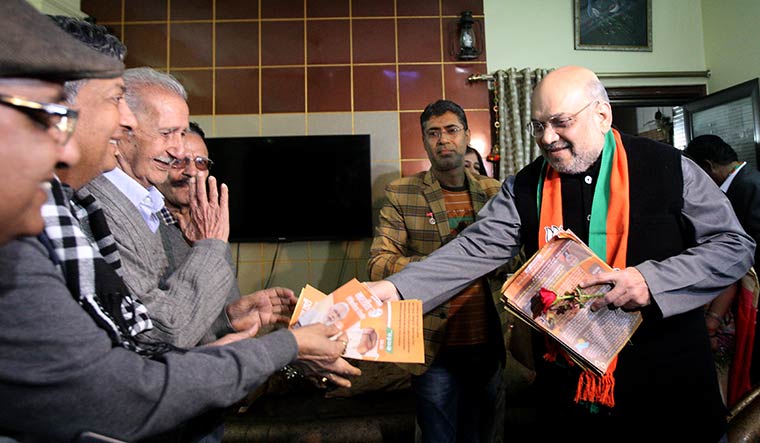

However, the party has claimed that the national agenda cannot be dissociated from state elections, and Amit Shah recently launched the BJP’s door-to-door campaign on CAA. “In Delhi, the national and local issues merge,” said senior BJP leader Vijay Goel. “CAA is a national issue, but does it not have local ramifications when protests lead to chaos in the city, when students cannot go to schools and take exams?”

The BJP’s opponents see the national-local mix as a reflection of the confusion in the party about assembly elections. Moreover, infighting in the party between the ‘original Delhi’ and ‘Purvanchali’ factions, along with the competing claims to chief ministership, has not allowed it to name a chief minister candidate. Shah even announced that there would be no chief minister candidate and the election will be contested under the leadership of Modi. The slogan is ‘Dilli Chale Modi Ke Saath (Delhi walks with Modi)’.

The third contender in the elections is the Congress, which had ruled Delhi for 15 years under Sheila Dikshit. The AAP usurped its vote bank—mainly Muslims, dalits and the migrant population—six years ago. And since then, the Congress has struggled to make a comeback, even though its vote share has increased.

It took the party leadership months after Dikshit’s demise in July 2019, to name her replacement as the Delhi Congress president. Finally, veteran Subhash Chopra, who was in the wilderness in the Dikshit era, was brought in to lead the party.

Seeking to tap into the goodwill for Dikshit, who Delhiites credit for the capital’s transformation, the Congress is comparing the achievements of its erstwhile government with the “chaos and misrule” of today. Its slogan captures the sentiment, saying, ‘Dilli Bole Dil Se, Congress Phir Se (Delhi says with all its heart, Congress one more time)’.

“Through our ‘Halla Bol’ campaign and numerous protests, we have exposed the failings of the AAP government and the BJP regime at the Centre,” said Chopra. “The people of Delhi recall the good work done by Congress governments.”

The Congress has also promised more benefits to the people of Delhi, namely 600 units of free electricity and an enhanced pension of 05,000 under the ‘Sheila Pension Yojana’. It has also promised free registry in unauthorised colonies.

The party, however, has struggled with organisational issues and has failed to form a cohesive force. The assessment even within the party is that it may end up wasting the advantage it had gained in the Lok Sabha elections, where it had pushed the AAP to third place in six seats.

While the party high command reportedly wants senior leaders to contest, those leaders would rather have their kin take the expected loss. In what could be a sign of a defeatist attitude, veteran Delhi Congress leader Mahabal Mishra’s son Vinay crossed over to the AAP on the eve of the elections; the AAP has fielded him from Dwarka.

However, where the Congress has been different is in its support of the anti-CAA protesters, with Chopra visiting them at Shaheen Bagh and meeting with injured agitators. This is apparently being done to win over the youth, the Muslims and the migrant population.

“Why is Arvind Kejriwal not holding a dharna in support of the students of Jamia and JNU?” asked Delhi Congress leader Mukesh Sharma. “He cannot shrug off responsibility by simply saying that the Delhi Police is not with him.”

The Delhi Police may not be with him, but February 11 will reveal whether the people of Delhi are with Kejriwal, once again.