For seven-year-old Ranjeev, breakfast is never complete without a tall glass of milk. His mother, Chitra, makes it even more nutritious by adding a spoonful of homemade multigrain powder. “I drink milk in the evening and at night, when I listen to bedtime stories,” says Ranjeev, a class 2 student at National Public School, Bengaluru. Chitra buys milk from a local milkman to ensure its safety, although packaged milk is readily available.

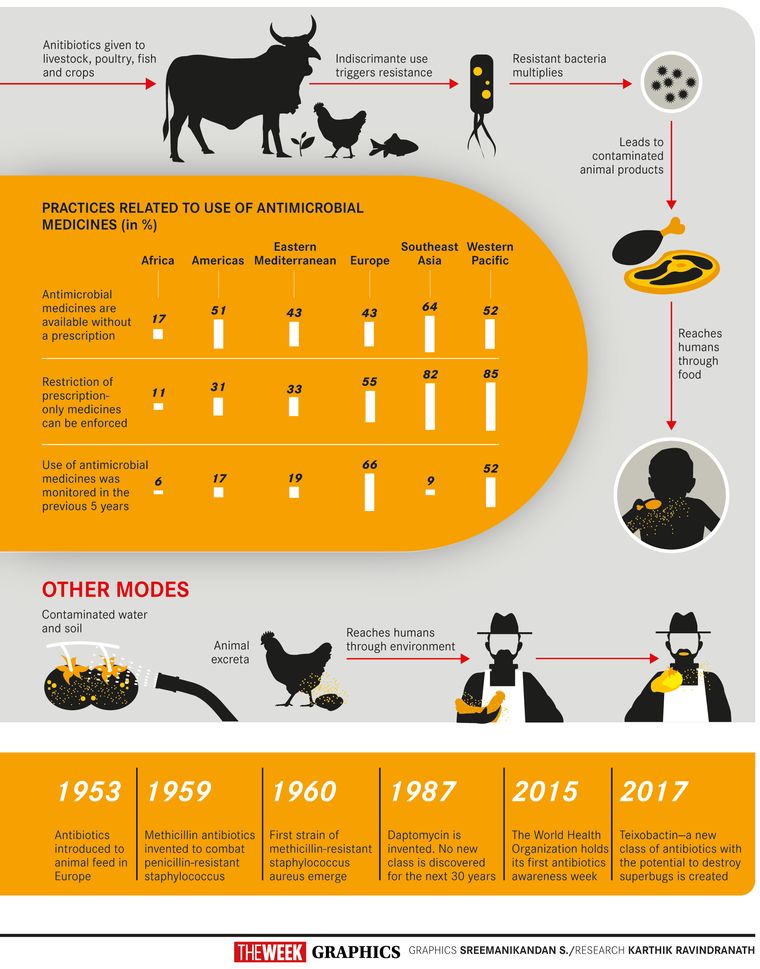

Chitra’s fears are not irrational. Antibiotic residue is present in most packaged milk brands, and also in milk-based products like ghee and butter, says Jubin George Joseph, chief operating officer of the Bengaluru-based Ramaiah Advanced Testing Laboratory. This is largely the result of antibiotics being administered to animals to prevent illnesses and also to fatten them up. World Health Organization estimates say that in some countries approximately 80 per cent of the total consumption of medically important antibiotics is in the animal sector, largely for growth promotion in otherwise healthy animals. “Antibiotics like ciprofloxacin are present in almost everything that we eat,” says Joseph. “Tetracycline and amoxicillin are found in chicken and milk. Some of the shrimp samples we tested had antibiotic residues 300 per cent above the permissible level. We have detected them in honey, drinking water and eggs. Some new generation antibiotics have been detected in pork.” Even fruits and vegetables are not safe. Tests done on samples of greens and curry leaves have shown antibiotic residues. With the presence of antibiotics in virtually everything we consume, the world—especially developing countries like India—is staring at the spectre of antibiotic resistance, which could, in about a decade, be the single biggest cause of deaths worldwide. In fact, antibiotics could soon kill more people than cancer and diabetes together could.

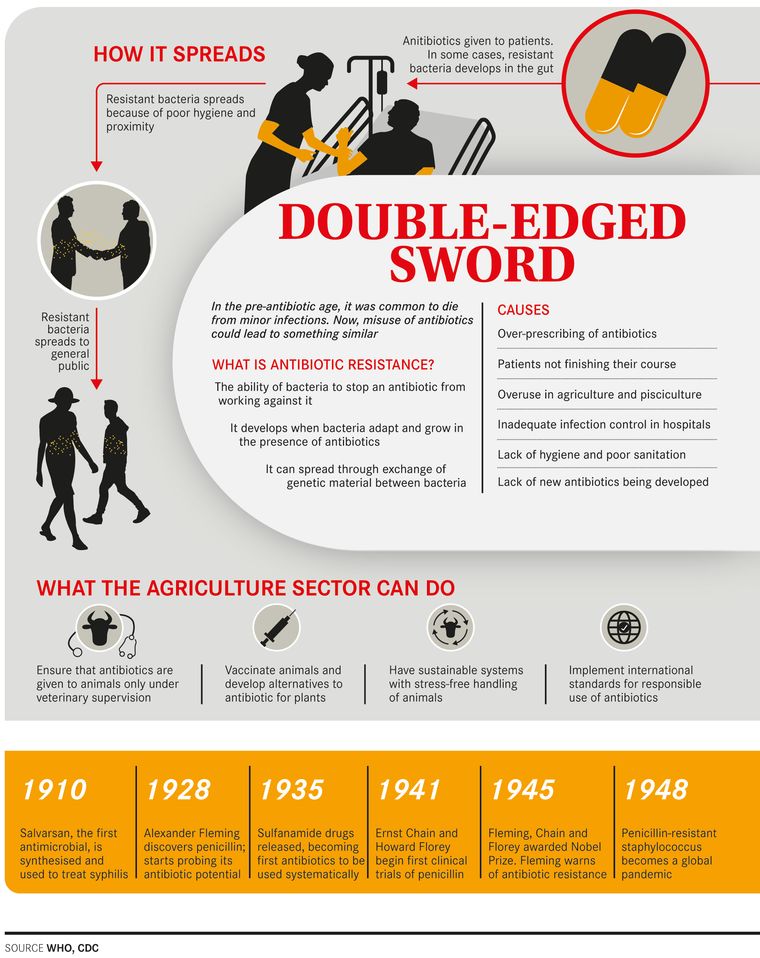

The WHO defines antimicrobial resistance (AMR) as the “resistance of a microorganism to an antimicrobial drug that was originally effective for the treatment of infections caused by it”. Antibiotic resistance is a subset of AMR in which bacteria acquire the ability to withstand the effect of an antibiotic, says Dr Rohan Sequeira, general medicine consultant at Mumbai’s Jaslok Hospital and Research Centre. It can occur both naturally or through a random mutation. “Once the evolution takes place in a bacteria, it can transfer this information to the next generation of bacteria. If it is single drug resistance, it is called mono-antibiotic resistant, but if it develops resistance to multiple drugs, then it is called multidrug-resistant bacteria, or superbugs,” says Sequeira.

The United Nations considers antibiotic resistance on par with Ebola and AIDS. According to the WHO, it could push 2.4 crore people into extreme poverty by 2030, and drug-resistant diseases could cause one crore deaths annually by 2050. Of these, 47 lakh deaths will be in Asia. At present, seven lakh deaths happen a year globally from drug-resistant diseases. The agency warns that more and more common diseases like respiratory tract infections, sexually transmitted infections and urinary tract infections are becoming untreatable because of antibiotic resistance. The economic losses could be devastating, estimated to be about $100 trillion in total by 2050.

In India, contamination of food and water sources have made the situation all the more alarming. For instance, a study conducted in December 2018 by the Indian Institute of Science Education and Research, Bhopal, and the Royal Institute of Technology, Sweden, has found a high prevalence of antibiotic-resistant bacteria in the Yamuna. The Ganga, too, is a major repository of antibiotic resistant bacteria and the Union government has sanctioned 09.3 crore to study the threat of antibiotic-resistant bacteria along the entire stretch of the river. Untreated effluent from pharmaceutical industries and hospital waste that contains antibiotics are polluting water sources. A recent study by the Indian Council of Medical Research, too, has come up with alarming findings—two out of every three healthy individuals tested as part of the study were found to be resistant to one or more antibiotic classes. Of the 207 participants in the study, 139 were found to have resistant bacteria in their digestive tract, though they had not used any antibiotics for a month prior to the test. Cephalosporins and fluoroquinolones—antibiotics commonly used to treat a wide variety of skin, respiratory and urinary tract infections—were found to have no effect on most of the participants in the study.

A study conducted in 2018 by Dr Abdul Ghafur of the Apollo Cancer Institute, Chennai, and Christian Medical College Vellore found the presence of bacteria resistant to colistin, an antibiotic of the last resort, in nearly 50 per cent of the food samples collected from Chennai. In fact, reputed brands were selling poultry feed containing colistin. The ads said that the feed was capable of preventing diseases and promoting growth. Alarmed by the growing misuse of colistin in the livestock industry, the government has banned its use in food-producing animals, poultry and aqua farms.

The indiscriminate use of antibiotics is not limited to the food industry. Self-medication, especially in developing countries like India, is a major threat. As antibiotics are easily available, people use them without prescription or medical supervision. On December 23, the Drug Controller General of India sent out an advisory asking all states and Union Territories to stop selling antibiotics without a doctor’s prescription. Antibiotics are placed under Schedule H of the Drugs and Cosmetics Rules (1945), which cannot be sold without prescription. Moreover, most third and fourth generation antibiotics are categorised as Schedule H1. Pharmacists need to retain a copy of the prescription while selling such drugs and maintain a separate register in which the name of the patient and the details of the doctor should be entered. The register will have to be kept for three years. But despite such restrictions, over-the-counter sales of antibiotics continue to be rampant.

Although antibiotics should only be used for confirmed bacterial infections, many patients and even doctors use them to treat flu or the common cold caused by viruses. In many cases, antibiotics are even used as the first line of treatment. India ranks first in the world in total consumption of antibiotics for human use. India also leads the world in the manufacture and use of spurious antibiotics.

Not completing a prescribed course can also contribute to antibiotic resistance. Sequeira says each course of antibiotics is designed to kill 80 to 90 per cent of the total bacteria in the body. “So, if five days of antibiotics are prescribed, that means it takes five days for the body to get rid of that many bacteria. Whatever remains in the body is taken care of by the body’s immunity,” he said. Patients sometimes stop taking the antibiotics once they start feeling better, thinking they are completely cured. “The patient feels fine because the antibiotics have destroyed more than 50 per cent of the bacteria. But the course is designed to kill 90 per cent. Just because symptoms like fever, cough and cold have subsided does not mean that the infection is gone,” says Sequeira. “Instead, it may have transformed from a clinical infection to a subclinical infection. Therefore, if you do not complete the course, the bacteria can again grow and can come back to a point referred to as relapse or, worse still, form a resistance to that antibiotic.”

Antibiotic resistance is a key threat to neonatal health. According to a study conducted by AIIMS, New Delhi, published in the British Medical Journal, drug-resistant bacteria affect 16 per thousand newborns in India. A third of those babies succumb to sepsis in a matter of days, according to the study.

Antibiotic resistance poses a major challenge to surgeries, a mainstay of modern medical care. Dr Devi Shetty, chairman and founder of Narayana Health, Bengaluru, warns that antibiotic resistance could threaten the future of surgical procedures. “We would have done a fantastic operation. But if the patient gets infected with a resistant bacteria, we are totally helpless. There is nothing you can do. And, such cases are increasing,” says Shetty, who has performed more than 15,000 heart surgeries.

Experts say that superbugs are present in intensive care units countrywide. Patients sometimes contract infections from hospitals, which jeopardise surgical outcomes. “Multidrug-resistant bacteria are very much present in our hospitals,” says Dr Chinnadurai R., lead consultant, department of critical care, Aster RV Hospital, Bengaluru. “Around 80 per cent of the patients who undergo major surgeries or get admitted in the ICUs with non-infectious problems develop multidrug resistance and end up taking more powerful antibiotics like polymyxin to combat it. Even a patient undergoing a simple surgery could contract drug-resistant infections from the hospital.”

Antibiotic resistance has increased the risk in procedures such as organ transplant, chemotherapy and caesarians. “A large per cent of deaths in hospitals, especially with pneumonia, sepsis and urinary infection, is caused by broad-spectrum antibiotic-resistant organisms,” says Dr Hemalatha Arora, who heads the department of medicine at Seven Hills Hospital, Mumbai.

What is more worrisome is that antibiotic resistance is becoming common even among individuals who have never taken antibiotics. Shetty says a study conducted by Narayana Health on 100 bypass patients has shown the extent of the problem. “These patients were villagers who had never taken antibiotics before,” he says. “But they had multidrug-resistant bacteria in routine swabs taken from various parts of their body.”

Also read

- Indore water contamination tragedy: Antibiotic-resistant E. coli a major public health threat

- India’s silent pandemic: Why antibiotics are failing and what it means for your health

- Amid rising fever cases, IMA advises to avoid antibiotics. Here's why

- Scientists discover medieval medicine that could be a useful future antibiotic

- OPINION: Time for India to step up fight against antimicrobial resistance

- India leading the way in averting antibiotic apocalypse

Antibiotic resistance poses a major threat to cancer patients who receive chemotherapy. They are immunosuppressed and are like “a country without an army and police”, leaving them defenceless against the bugs. A study by the department of microbiology of AIIMS, New Delhi, has shown antibiotic resistance to be the leading cause of death in leukaemia patients, forcing many cancer patients and their doctors to weigh the pros and cons before starting a course of chemotherapy. “It is disturbing to see how antibiotics are losing their effectiveness,” says Dr Sachin Jadhav, group head, haematology and bone marrow transplant, HCG Group of Hospitals.

Many of the deaths due to infections are preventable. “With better use of diagnostic tools we can reduce the use of antibiotics and prevent antibiotic resistance,” says Jadhav. “Since routine diagnostic tests such as blood culture are not sensitive enough, when somebody has a infection, about 80 per cent of the time doctors end up giving a combination of antibiotics. But some of these may not work at all.”

Newer diagnostic tests offer much hope to patients. Hanumanthappa from Bengaluru, was undergoing chemotherapy for the treatment of blood cancer. The 54-year-old had a minor cold, which turned into a serious lung infection as he was immunosuppressed. Jadhav gave him four antibiotics and an antifungal, hoping that one of those would work. “I did not know what kind of infection it was,” says Jadhav.

Later he tried a newer diagnostic tool called the Syndrome Evaluation System (SES), and found that Hanumanthappa’s infection was caused by five different bugs. “SES helped me tackle the infection more effectively and reduce the number of antibiotics,” says Jadhav. “By then, however, it was too late and the patient did not survive. With the timely use of such newer technologies, we have now managed to implement rational use of antibiotics. This reduces cost and dramatically decreases the chances of death from serious infections.’’

Tuberculosis kills more people globally than any other infectious disease. India is among the top three countries with the most TB cases globally. “Drug resistance is a major challenge in the treatment and management of tuberculosis. The resistant bacteria are far more challenging to treat and can also be transmitted to others,” says Dr Camilla Rodrigues of P.D. Hinduja Hospital, Mumbai.

SPIT SEQ (spit sequencing) is considered to be a significant breakthrough in the war against multidrug-resistant TB. “It is much superior to conventional tests as it does not need a culture, which takes a long time,” says Dr V.L. Ramprasad, chief operating officer of MedGenome, the genetic diagnostic company that developed SPIT SEQ. Traditional culture takes about six to seven weeks to grow, while SPIT SEQ can be done in less than 10 days.

In 2017, India put in place a National Action Plan (NAP) on antibiotic resistance, on the lines of the WHO’s global action plan. The NAP focuses on improving awareness through communication, education and training, strengthening knowledge through surveillance, effective infection control, optimising the use of antibiotics, promoting investments for further research and strengthening India’s leadership on the issue. The NAP has not gone far, sadly.

Although the bigger burden of antibiotic resistance is borne by developing countries like India, no part of the world is safe from this rapidly growing menace. In January 2019, a team of scientists from Newcastle University in the UK tested soil samples (collected in 2013) from Svalbard, a remote Norwegian island chain in the Arctic circle. They found as many as 131 antibiotic-resistant genes in the soil samples, including the New Delhi metallo-beta-lactamase-1 gene or NDM-1, which makes bacteria resistant to carbapenems, considered to be the antibiotics of last resort. NDM-1 was first identified in hospital settings in a Swedish traveller in New Delhi in 2008. By 2010, its presence was confirmed in Delhi’s groundwater. So, in a matter of three years, NDM-1 travelled nearly 7,000km and managed to thrive in a remote geographic location with negligible human presence and sparse flora and fauna, indicating the fearsome scale, scope and spread of antibiotic resistance.

Apart from the threat it poses to India’s public health system and its 1.3 billion residents, the fear of antibiotic resistance can also hurt India’s already tenuous economic situation, scaring away tourists and businessmen. On August 25, 2016, a 70-year-old lady from Nevada, United States, was hospitalised with an infected hip. She was previously in India on an extended visit, where she broke her thigh bone and had to spend several days in hospital. The US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) identified that she was infected with Klebsiella pneumoniae, a superbug with the NDM-1 gene. The patient, however, did not respond to all 26 antibiotics available to treat the infection in the US, and died of sepsis two weeks later. It was one of the first cases in the US where the doctors could not save a patient even after identifying the bacteria well in advance.

Experts worry that the situation is unlikely to get better in the near future as not enough research is happening. No new classes of antibiotics have been developed for the past few decades, especially the ones that could target Gram-negative bacteria, the primary menace in the developing world. “There is no big money in antibiotics,” says Shetty. “The industry will put money in medicines which patients have to take for life. Antibiotics are given only for seven days. So pharmaceutical companies do not see any big money in it. Moreover, once the bacteria develop resistance, the medicine could become useless.”

*Some names have been changed.