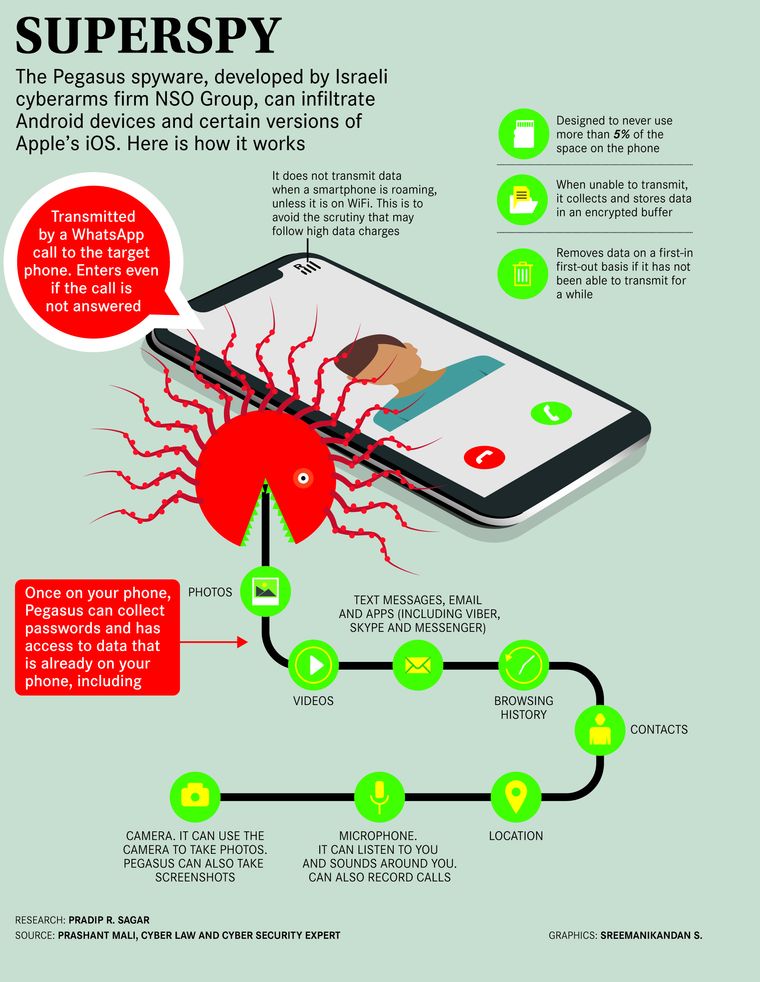

It lands on your cellphone with its giant wings flapping, penetrates the phone’s operating system, reads messages and emails, cracks passwords, tracks your location, and even accesses the mic and the camera. It is Pegasus, a dangerous spyware named after the winged horse in Greek mythology, and designed by the Israeli cyber-intelligence firm NSO Group to hack into cellphones through WhatsApp, the multimedia messaging platform owned by Facebook.

Pegasus can infect devices running on Apple’s iOS and Google’s Android operating systems. Its snooping prowess is notorious—1,400 individuals in 45 nations have been targeted so far. India woke up to the Pegasus threat only recently, when it was revealed that 121 of the victims were Indians, most of them lawyers, activists and journalists.

NSO Group says it sells Pegasus to government clients only. So, when Congress general secretary Priyanka Gandhi Vadra revealed that she, too, was targeted, it resulted in an avalanche of allegations that the Union government was behind the snooping. “When WhatsApp sent messages to all those whose phones were hacked, one such message was also received by Priyanka Gandhi Vadra,” said Randeep Surjewala, chief spokesperson for the Congress, on November 2.

Four days earlier, WhatsApp had filed a lawsuit against NSO in a US court, saying Pegasus piggybacked on its app to infect cellphones. With 400 million users, India is WhatsApp’s biggest market. To contain the fallout from the security breach, the messaging giant has gone all out to assure users that their privacy and security remained its highest priority. It has reached out to the victims, asking them to update the app to protect themselves.

Shubhranshu Choudhary, a former BBC journalist who is now an activist in Chhattisgarh, was one of the victims. “I assume that I came under the scanner because of my work,” he told THE WEEK. “We have created a platform called Voicebook—like Facebook—where adivasis from six states affected by left-wing extremism can share grievances and suggest ways to address them. Voicebook records their messages in the local dialect and we translate it. Anyone who dials our number can listen to it, just like you can read Facebook messages.”

According to Choudhary, intelligence agencies would have wanted to know whether he and his colleagues had links to the Maoists. “I feel this is an opportunity for the government to bring a law to protect the right to privacy of citizens, while empowering law enforcement agencies to gather intelligence in a productive way,” he said.

Shalini Gera, a Bastar-based lawyer who has appeared for jailed activist Sudha Bharadwaj, said the surveillance pattern showed that activists working to solve dalit and tribal issues were targeted. “I have been targeted before,” she said. “The legality or illegality of such surveillance is hardly an issue, as these things happen. I am not doing any illegal work, so I have nothing to hide. However, I lost my phone recently, so I am relieved that I don’t have the same phone.”

Unlike Gera, Choudhary is educating himself on digital security. He is also training his co-workers to secure and defend themselves online. “We have to be more cautious to protect our privacy and fundamental rights. It has to become a part of life today,” he said.

How Pegasus lured targets and captured their phones was first revealed in 2013, when UAE-based human rights activist Ahmed Manzoor received several links on his phone. Aware that he had been targeted by the government earlier as well, Mansoor forwarded the links to Citizen Lab, a cyber espionage research group based at the University of Toronto.

Citizen Lab red-flagged it as a snooping attempt. Behind it was NSO Group, founded by Unit 8200 of the Israeli Intelligence Corps, whose ability to collect signals intelligence was on a par with the National Security Agency of the US. Pegasus, which was NSO’s flagship product, was first sold to the Mexicans fighting drug cartels.

Pegasus gained notoriety when it was alleged that Saudi dissident and journalist Jamal Khashoggi’s phone was hacked. Khashoggi was killed last year in Saudi Arabia’s consulate in Istanbul. Khashoggi’s friend Omar Abdulaziz and Amnesty International filed cases in Israel against NSO.

The Indian government has denied allegations that it employed Pegasus for unlawful surveillance. The Union home ministry said the government was committed to protecting the fundamental rights of citizens and that “reports of breach of privacy of Indian citizens on WhatsApp were attempts to malign the government and are completely misleading”.

Gulshan Rai, who was national cybersecurity coordinator in the Prime Minister’s Office, said there was no reason to disbelieve the government. “It has denied all allegations and there is no reason to disbelieve it,” he said. “The government obtains data related to crime and terror incidents in accordance with the law, and has never tried to take undue advantage of any company like WhatsApp. The fact is that the government has been trying to enforce the law by asking WhatsApp to set up a server here.”

WhatsApp had been preparing to enter the digital payments sector in India. Rai said the latest challenge for the government would be to ensure the sector remains safe. “The Reserve Bank of India has asked WhatsApp Pay to comply with its data localisation norms, which mandate it to house the data in India,” he said. “The fact is that the laws are in place and the [government’s] intention is right. The issue is to enforce the law and make these companies follow rules and regulations.”

The cyber and information security division of the Union home ministry, established during Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s first term, said that there was no information of any order being given to purchase Pegasus. Only ten agencies in the country have the mandate to carry out surveillance activities. These are the Intelligence Bureau, the Central Bureau of Investigation, the Enforcement Directorate, the Research and Analysis Wing, the Narcotics Control Bureau, the Central Board of Direct Taxes, the Directorate of Revenue Intelligence, the National Investigation Agency, the Directorate of Signal Intelligence (in Jammu and Kashmir and the northeast) and the office of the Delhi Police commissioner. Similar powers are granted to state law enforcement agencies only if the state home secretary approves it.

NSO, which is based in Herzliya, Israel, does not carry out surveillance activities on its own. It says its products are “licensed to government intelligence and law enforcement agencies for the sole purpose of preventing and investigating terror and serious crime”.

When contacted by THE WEEK, an NSO spokesperson in Herzliya denied allegations of misuse, but said the company could not disclose “who is or is not a client, or discuss specific uses of its technology”. “In the strongest possible terms, we dispute allegations and will vigorously fight them,” said the spokesperson. “Our technology is not designed or licensed for use against human rights activists and journalists.”

According to the company, its products have helped save thousands of lives in recent years. “The truth is that strongly encrypted platforms are often used by paedophile rings, drug kingpins and terrorists to shield criminal activity,” said the spokesperson. “Without sophisticated technologies, law enforcement agencies face insurmountable hurdles. NSO’s technologies provide proportionate, lawful solutions to this issue.”

What if the technologies are misused? “We take action if we detect any misuse. This technology is rooted in the protection of human rights—including the right to life, security and bodily integrity—and that is why we have sought alignment with the United Nations Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights, to make sure our products respect all fundamental human rights.”

Asked whether the NSO disclosed the identity of clients who misuse Pegasus, the spokesperson said, “To protect the ongoing public safety missions of its agency customers, and given the significant legal and contractual constraints, NSO Group is not able to disclose who is or is not a client, or discuss specific uses of its technology. However, the company’s products are licensed to government intelligence and law enforcement agencies for the sole purpose of preventing and investigating terror and serious crime.”

Also read

- Malware found in phones, but ‘inconclusive’ if Pegasus: Supreme Court

- Pegasus: SC extends time for submitting probe report on use of Israeli spyware

- Spanish Prime Minister's phone was infected with Pegasus spyware: Government

- Bengal was offered Pegasus spyware for just Rs 25 crore: Mamata

- Pegasus: Investigations worldwide hold a crucial lesson for India

- FBI says it purchased Pegasus spyware to evaluate it

- Pegasus probe: Why India's surveillance laws need a relook

According to Rai, tech firms like NSO cannot be blamed for trying to sell their products. “Just like companies that sell arms and ammunition, NSO, too, is selling its products,” he said. “Should we blame the companies that are selling arms and ammunition, or question those who collaborate to misuse these arms and ammunition?”

G.K. Pillai, who was Union home secretary from 2009 to 2011, said legitimate surveillance firms like NSO have long been doing business in India. “As we speak, Pegasus may have evolved into another form and another name. It only needs a bit of tweaking and a change of name to turn an existing spyware into a new spying software,” he said.

Pillai said start-up parks for cybersecurity companies have been instrumental in making Israel a cyber superpower. “Experts in the field of cyberspace are sent to these parks, where they develop software funded by Israeli agencies. It is after the Israeli army and intelligence agencies have used these software, that they are sent out to the commercial market,” he said.

While cyber-intelligence agencies across the world have moved on to tiny, high-end spyware, Indian intelligence agencies are left tracing off-the-air machines (which help in recording conversations) that went missing nearly a decade ago. When Pillai was home secretary, he had directed states to gather all surveillance equipment with law enforcement agencies and private firms and hand them over to the Intelligence Bureau. Top sources in the IB said that there were around 2,000 such machines in India, but only 100 were handed over to it. The remaining machines are still missing.

An intelligence officer recounted an episode when a senior Congress leader was travelling in a car through Shantipath, the main road in the diplomatic enclave of Chanakyapuri. The leader’s phone came under surveillance inadvertently, which led to a huge controversy. The culprit was an off-the-air machine installed outside an embassy that caught traffic it was not supposed to pick.

The security establishment is miffed at WhatsApp for delaying information about the breach and not providing all details. It was in May this year that WhatsApp notified authorities in India and abroad that its security team had prevented a cyberattack on mobile devices. But security officials say it should have notified CERT-In, the government’s nodal agency that deals with cybersecurity threats, at least months earlier.

“Countries like South Africa had already faced the Pegasus breach in September 2018. If WhatsApp was aware of the vulnerability in its system, it should have been conveyed [to CERT-In] immediately,’’ said a senior government official.

Apparently, the WhatsApp alert in May was about a technical vulnerability, and not about breach of privacy. Pegasus was not mentioned. When the second alert came in September, the government swung into action, but the breach had already taken place and resolved by then.

The slow response of both WhatsApp and CERT-In has exposed the chinks in India’s cybersecurity armour. Other than asking WhatsApp to explain why the government was not adequately informed of the breach, the government has neither asked an independent agency like the CBI to inquire into the matter nor registered a first information report.

“WhatsApp has betrayed the trust of its users by abetting unauthorised access, which is a cyber crime under the Information Technology Act, 2000,” said Prashant Mali, lawyer and cybersecurity expert in Mumbai. “The government can file a case and proceed against WhatsApp. This will create a deterrence for other social media companies, too.”

Senior lawyer Shariq Nachan said investigating WhatsApp was futile, as the platform itself was a target of the breach. “NSO has no presence in India and, therefore, it is not possible to investigate them. There is also no way to enforce their cooperation. WhatsApp has become the easy target as of now. But there is definitely a need to investigate who engaged NSO to snoop on activists, journalists and politicians,” he said.

Ethical hacker Khushhal Kaushik, who helps security agencies solve cases and train personnel, said users of Chinese smartphones are especially vulnerable. “There is no need to inject Pegasus into their phones, because the phones have apps that are preloaded,” he said. “Because they [the phone makers] do not have a data centre in India, the users become vulnerable to monitoring by Chinese intelligence agencies.”

Amid the blame game between WhatsApp and the Indian government, people have begun trying alternative messaging platforms like Viber and Telegram to protect themselves from governments, companies and even mercenaries. But, with the ever-increasing sophistication of surveillance technologies, one thing is evident: there are not enough precautions that you can take to prevent your phone from becoming the next target.