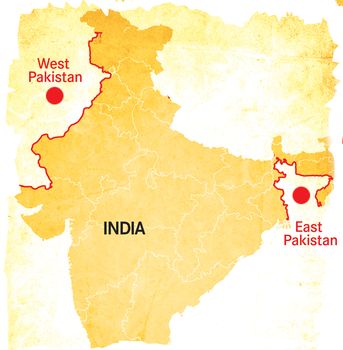

In March 1971, Pakistan launched Operation Searchlight to curb the Bengali nationalist movement in East Pakistan, which resulted in the massacre of one million Bengalis. Ten million refugees fled to India, creating a huge financial and security headache. Prime minister Indira Gandhi wanted Sam Manekshaw, chief of the Army, to launch an attack, capture territory and send back the refugees. Manekshaw, however, famously told her it was not the right time. The monsoon was approaching, and tanks would be useless in that weather. The tanks were not yet battle ready. “He wanted to choose the time and place of the offensive, and for the first and only time in post-independence history, the prime minister listened to the military,” recalls retired Major General Ian Cardozo, veteran of the war and author of several books on the Indian military.

Manekshaw needed time to prepare his forces. He also wanted the winter snows to set in, ensuring no Chinese help could come for the enemy. “In every other war before, we were caught by surprise; this was the only time we were not,” says Cardozo. The Indian troops began preparing for the ‘moment of truth’. In New Delhi, chiefs of the three services sat together, planning how to deploy men and machine. Major General J.F.R. Jacob, chief of staff under eastern army commander Lieutenant General J.S. Aurora, set up a wireless interceptor between Karachi and Dhaka, and began listening to the enemy’s plans. When Pakistan attacked India’s airfields in the north on December 3, India was ready for war.

It was a war of innovative thinking, which, when combined with the valour of the Indian soldiers, was a win-win formula. The Navy deployed its missile boats, newly acquired from the USSR and meant for harbour patrolling, to launch attacks on Karachi harbour and Keamari oil farms. The blasts are still recalled in naval lore as the biggest Diwali they have seen. The western fleet left Bombay harbour, after receiving the intelligence of a likely attack there. Pakistan’s Daphne-class submarine, PNS Hangor, was lurking in the Arabian sea, and it torpedoed the frigate INS Khukri. The remaining fleet, however, remained unscathed. The Navy hid its prized carrier INS Vikrant and used a decoy, INS Rajput, to lure the Tench-class submarine PNS Ghazi into Visakhapatnam. The subterfuge was honed to perfection. Rajput sent regular messages (for Pakistan to intercept) demanding amounts of fuel and food befitting a carrier. Ghazi made one fatal mistake; it did not realise that Visakhapatnam was too shallow for a vessel of Vikrant’s draught. Ghazi blew up as Rajput made a stealthy exit.

The Indian Air Force drew its first blood 12 days ahead of the war, when, on the eastern theatre, four Gnats shot down three Pakistani Sabres. The first prisoner of war, Captain P.Q. Mehdi, later went on to become Pakistan’s air chief. Stories of the war are still tumbling out. A recent book, In the Ring and on its Feet, by retired Air Commodore M. Kaiser Tufail, a Pakistani war historian, details the carnage unleashed on Murid air base by four Hunters of the No 20 squadron of the Indian Air Force; the Hunters brought down five Sabres in a single air raid on December 8. Pakistan’s air power was rendered immobile in the first week of the war. The surviving aircraft took refuge in Iran.

A two-pronged strategy—offensive defence on the western theatre and pure offensive on the eastern theatre—progressed even better than expected. The Battle of Longewala (December 4 to 7), where one company of the 23rd battalion of Punjab Regiment battled with a column of 45 armoured tanks, is often compared to the Battle of Thermopylae, except that India lost just two soldiers. Commanding officer Kuldip Singh Chandpuri had been told that reinforcements would take six hours and that he could retreat. He decided to fight, instead. With just a few medium machine guns, one mortar and a jeep-mounted recoilless rifle, they not just held out the night, but claimed 12 Pakistani tanks. With dawn came air support. The IAF team, not equipped for night flying, was itching for action, and claimed another 22 tanks. Then, when Indian armoured vehicles and infantry launched their attack, Pakistan was forced to withdraw.

“The capture of Dhaka was not in the initial plan, but when we realised we were succeeding beyond expectation, the race for Dhaka began,” recalls Cardozo. Here again, India used innovation. “The commander-in-chief of East Pakistan, Lieutenant General A.A.K. Niazi, had planned the defence of Dhaka on a fortress concept, with major towns and rivers as obstacles. Had we gone through these defences, we would have been stuck. Instead, we bypassed them, and took Dhaka.”

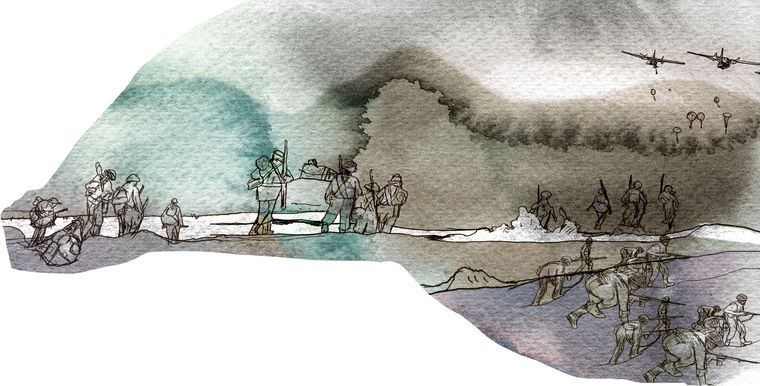

So, on December 11, India airdropped 540 paratroopers around Tangail, less than 100km from Dhaka. Their mission: Stop retreating Pakistani troops from marching into Dhaka by capturing the Poongli bridge, and then join the infantry and head for Dhaka through the undefended Manikganj route.

It was the first time such an operation was being conducted in South Asia; no one even thought India had the wherewithal for it. The paratroopers were the first to enter Dhaka. The Army did some dummy drops, too, making the exercise seem bigger than it actually was.

News reports of the airdropping did not have an accompanying picture, so the officer in charge of publicity pulled out one of an exercise in Agra some time before, deliberately omitting to mention that it was a file picture. Everyone from the reader of The Times in London to Niazi in Dhaka felt an entire brigade was paradropped.

Niazi could have defended Dhaka for a few more weeks. But, he buckled when Manekshaw sent messages saying he was surrounded. This resulted in the famous Instrument of Surrender, and “India’s first outright victory in 3,000 years,” says Cardozo.

The outcome of this victory was phenomenal. India had carved out a new nation, and emerged as the dominant force in the region. The victory was the triumph that the people badly needed, after millennia of having fought well, yet losing.

Ask war historians what would have happened if the outcome had been different, and they smile and say, there was only one outcome for this war. It could have dragged on for a few more weeks; perhaps the US would have tried entering the scene. But, the USSR was patrolling the open seas for this eventuality. India would still have won.

Most of the gains of the war, however, were squandered in the Shimla Conference next year, where India returned captured territory. Could India have bargained, using this territory, for a permanent solution to Kashmir? Unfortunately, even as victors, India could not make Pakistan return 54 POWs.