Everything, everywhere, all at once. There is a method in the spend-big-or-go-home madness that the finance minister has reiterated her faith in with the Union Budget 2023, even though a lot of it rests on hope.

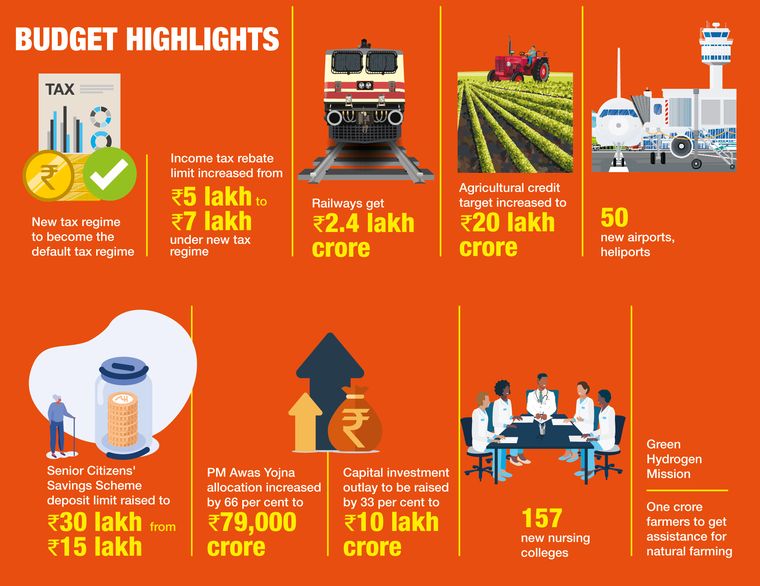

Nirmala Sitharaman’s budget, the last full one before the Lok Sabha elections next year, was a no-holds-barred buildup on spending from her own previous budgets (and the super budget that was lockdown’s ‘Atmanirbhar Bharat’ stimulus measures). While a whole lot of government spending last year was primarily in infrastructure like roads and ports, the largesse now has a wider arc―agritech, affordable housing, green energy, railway, airports and even helipads.

“This budget injects new vigour into India’s development trajectory, [it] will realise the dreams of an aspirational society that includes poor, middle-class people and farmers,” said Prime Minister Narendra Modi, shortly after Sitharaman tabled the budget in Parliament.

FOLLOW THE MONEY

In the run-up to the budget, Sitharaman had two paths before her―continue with the spending pattern or get conservative in controlling the runaway fiscal deficit (the gap between what the government earns and what it spends). The pandemic had seen the fiscal deficit shoot up to nearly 10 per cent, while the fiscal responsibilities rules limit was 3 per cent.

Interestingly, Sitharaman has pulled a bunny out of her hat by going in for both―spending even bigger, even while setting ambitious targets for taming the fiscal deficit. “This is a budget that has been beautifully balanced,” she said, besides adding how “fiscal consolidation has not been kept on the back burner.” The fiscal deficit has already come down to 5.9 per cent, but Sitharaman is emphatic that it would be brought down to 4.5 per cent in three years.

ALL ROADS LEAD TO…

Ever since the Covid pandemic started, the Modi government had embarked on a strategy of gambling on big capital spending, under the premise that it would beget growth in the long run. In fact, in this year’s budget, the capex has been increased over and above last year’s massive amount by 33 per cent―the effective spending estimated for the upcoming financial year will be a ginormous 013.7 lakh crore, which is about 4.5 per cent of the country’s gross domestic product (GDP). “Investment in infra will increase demand in multiple industries. It has a multiple beneficial impact,” said T.V. Narendran, managing director of Tata Steel.

It may be beneficial in the long run as well. “This capital expenditure, the government hopes, will lay the foundation for the future,” said Sethurathnam Ravi, economist and former BSE chairman. “Without growth, it is difficult to bring the fiscal deficit down.”

The motive is clear in the many customs duty rejigs, which will join the ‘Atmanirbhar Bharat’ initiatives announced earlier; all pushing the same thing―manufacturing locally. “The government has aimed to boost domestic manufacturing by simplifying manufacturing duties and indirect taxes. This decision is a much-awaited one,” said Arjun Bajaj, director of the company that makes Daiwa televisions. The budget has lowered import duties on items like TV panels, mobile phone components and camera lenses, aiming at not only domestic manufacturing, but also attracting global makers to set up factories in the country.

Even the reworking of personal income tax slabs has a motive. “The government has created more disposable income at the lower end and the middle income which will find ways into consumption, in turn boosting the economic growth,” said Shishir Baijal, chairman and managing director of the realty consultancy Knight Frank India.

It is a strategy the government is sticking to. That the government’s capital expenditure will spur the private sector to spend more, thus creating jobs, jacking up consumption and fuelling trade. With the expansion of the economy, tax and duty revenues will start flowing in. But there are big problems here.

ALL EGGS IN ONE BASKET

The first one is that reality has veered wildly off the original script. The expected capital expenditure from businesses have not really materialised. On more occasions than one, a frustrated finance minister had called them out. While big corporates were waiting for a revival of private consumption before they made business bets, the small and medium business were handicapped as they have not fully recovered from the impact of the lockdown. The easy loan scheme launched for them by the government as part of stimulus measures has had only limited success, mainly because banks were reluctant to loosen their purse strings.

Yet, North Block, the Raisina Hill monolith that houses the finance ministry, has continued to place its faith on the same strategy. This is because of a windfall coming in from unexpected quarters. The new economy, consisting mainly of tech firms flush with foreign funds and a curious K-shaped economy with the ‘haves’ splurging big (while the ‘have-nots’ are retreating into invisibility), has been seeing record GST revenues on a monthly basis. In the chaotic post-Covid economy, certain sectors made hay while others struggled. India’s exports boomed in 2021-2022 before it started cooling down eventually.

Even the Ukraine war―which led to fluctuations in commodity prices, oil prices and the value of the rupee―did help in some trade gains as India quickly moved in to take advantage of the west’s sanctions on Russia. But this kind of windfall cannot be expected to last forever. There are already the threats of high inflation and a global recession in the air, no matter how many times you repeat the phrase “Indian economy is resilient”.

Secondly, where is the money going to come from? For all the higher tax revenues, the cold truth is that the government will end up borrowing quite a bit, even if there are provisions for many of the ambitious projects to be public-private partnerships or to be funded jointly with state governments.

To fall back on an upward swing in revenues to take care of the mounting debt is foolhardy. “The global economy is very fragile,” said Ravi. “Our exports are already slowing down. We also have to be watchful of currency fluctuations, as well as fluctuations in the price of commodities.”

Sitharaman knows it too well. Many calculations in the last budget, based on the then price of crude oil went topsy-turvy when Russia invaded Ukraine, sending oil prices up and the value of the rupee down. It is another matter that those fluctuations led to a windfall for India later.

By doling out liberally for a rainbow spectrum ranging from the rural poor to the urban lower middle class, Sitharaman may have sewn up the political benefits. But when it comes to the economy, the best laid plans would depend on a lot more than praying for a best case scenario. “The budget aims that fiscal impulse is maximised to improve potential growth,” said Madhavi Arora, lead economist at Emkay Global Financial Services. “This requires continued financial sector reforms and better resource allocation.”