I am going to build the McDonald’s of India!”

The business bug bit Eshwar K. Vikas fresh out of college. He started Mukunda, a restaurant serving idli and dosa at a mall in Chennai, borrowing from his parents and friends to rent the space and set up a self-service model with large screens and LED lighting. He bought the batter from someone else and set about with his ‘McDosa’ dreams.

“Business was good from day one,” Eshwar recalled. So much so that he committed the blunder of his career—a second outlet on a franchisee model through a friend. “That was when I realised we were not able to maintain the consistency of the batter,” he said. To add to his woes, the ‘dosa master’, the guy in the kitchen, left. Customers stopped coming back, complaining that the quality had gone down.

An engineer, Eshwar wanted to solve the issue by getting a machine that can make dosas uniformly. The problem? There wasn’t one.

He did not give up. He refashioned an Archimedes screw, used to pump concrete mix in construction, into a pump for dosa batter. A person was assigned to design and make a tawa (wok) for the machine. And presto, Eshwar had pivoted from running a ‘manual’ restaurant into an automated kitchen.

Today, Eshwar is the go-to man in kitchen automation and robotics, with his machines DosaMatic, Eco Fryer, RiCo and Wokie used to make dosas, rice, noodles, momos and curries without human intervention. In the latest funding round two months ago, by the likes of Zomato which is rumoured to be using his machines in its 10-minute delivery, he raised around Rs60 crore. Driven by the demand, Eshwar has pivoted into running micro cloud kitchen factories, where he runs the machines in one location, uses ingredients supplied by multiple brands, and delivers through agents of Swiggy and Zomato. “Kitchen automation has slow scale of growth, but kitchen-as-a-service will grow very fast,” he said.

Ambitious, innovative and riding on technology and easy funding, people like Eshwar are driving an entrepreneurial revolution in India. It is fuelled by massive investor cash inflow from abroad, and indications are that even a recent tapering of this stimulus-driven funding will not slow down India’s tryst with the business bug.

“Fifty-three crore youth are the future,” said Dharmendra Pradhan, Union minister for education, skill development and entrepreneurship. “They will have to become employers to make India an entrepreneurial economy.”

The number of Indian unicorns—startups with valuations of more than $1billion dollars—crossed 100 early this summer. That makes India the fastest growing startup ecosystem in the world, and also the third largest, after the US and China. Indian Angel Network, a firm that invests in startups, said it got 30 applications for funding in 2006, the year it started; today it gets 75 a day.

Last year, around Rs28,000 crore was invested in privately held startups, with about 400 of them getting investor money for the first time. No longer is a bank loan or a handout by parents the only source of funding for a business with a good plan. The explosion of private investors, angel funds and venture capitalists has ensured that there are multiple sources a sharp mind with a bright idea can tap.

“It is a great time to be an entrepreneur in India,” said Vikram Gupta, founder & managing partner of IvyCap Ventures, one of India’s leading funding companies. “See how Zomato created value without turning in profits. Questions of ‘how can a startup be valued at a billion and not even have profits’ have already been answered.”

The rush of the ordinary Raj and Rahul (and his mate from IIT) becoming entrepreneurs is surprising because getting a salaried job had always been considered a better option in India than the risky proposition of starting one’s own business. Padmaja Ruparel, founding partner of Indian Angel Network, recalled how her parents told her to look for a job when she started her business. “Today parents come to me saying ‘my son is doing a startup’,” she said. “When I tell them about the possibility of failure, they say, koi baat nahi, we will look for a job then!”

The tipping point, perhaps, was the 1991 economic reforms. Out went the quota and licence raj, and entrepreneurship bloomed. While the first wave had existing business leaders expanding their coffers or multinational biggies making their presence felt, the dot com boom and the e-commerce explosion made it all real for ordinary aspirants. Governments, too, turned proactive, offering funds and looking for startups with innovative solutions to problems.

Somewhere along the way, failure became a stepping stone for learning, rather than a dead end. “Today, entrepreneurs do not fear failure, and are envisioning building world class companies out of India,” said Vishesh Rajaram, managing partner at Speciale Invest, an early-stage venture capital firm.

Education also played a part, with many private universities and coaching centres focusing on practical training and setting up entrepreneurship cells. “We are slowly moving away from employment seeking education towards skill-based and entrepreneurship-focused education,” said Ashish Munjal, co-founder and CEO of Sunstone, a higher education group.

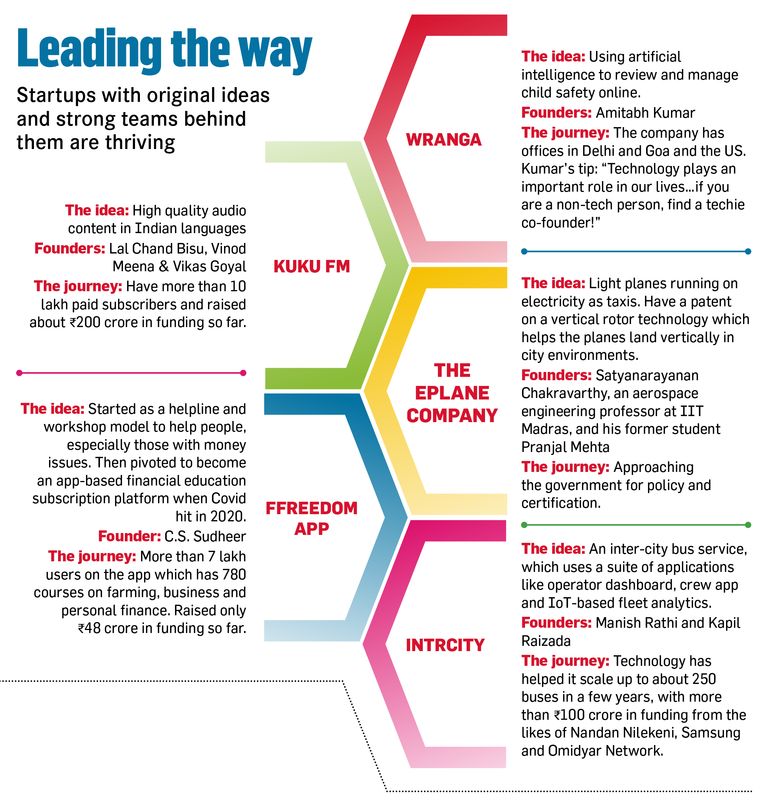

Yet, the true enabler of change has been technology. “Technology helps you speed up your business and execution,” said Manish Rathi, co-founder of the bus operator IntrCity. “Idea is still at the core of it, but tech has made it simpler.”

He should know. While some of the big private bus transport companies took decades to build a fleet, IntrCity took just about two years. “What are we doing different? Technology,” said Rathi. “Traditional businesses depended on trusted hands, usually relatives, to monitor new branches or inventory as businesses expanded into other locations. For us, it is simply technology. We are able to add 50 new buses a month because technology helps us monitor and keep track of performance.”

“Technology is the only way to reach out to a large number of people faster,” said Vikram of IvyCap. For investors, it is even more important—a company that can scale up fast using technology is very attractive, because a typical VC would be looking to cash out in a few years.

The process of startups getting funded works both ways. Anyone from international investors like SoftBank and Tiger Global to local funds created by families or companies and even Union ministries and educational institutions is ready to invest in startups that appeal to them. Funding also ranges the whole gamut, from early seed (first time) and angel investors (providing mentoring to startups who have just about started operating) to multiple series, which are titled Series A, B, C and so on. Some companies at a later stage then venture on to the stock markets by going for an IPO.

Investor Arjun Vaidya breaks it down: “50 per cent depends on the founder, the person or persons behind a startup. We look for whether they will be resilient when things are tough, and whether they are best placed to solve the specific problem at hand.” The remaining he breaks down to 20:30 between whether the market for the product or service is big enough and the rest on the business metrics, ranging from sales, growth velocity, gross margin, profitability and team members.

Of course it helped that the past two years had investors flush with cash looking for opportunities. This was fuelled by the excess money pumped into the system as a post-Covid stimulus measure by countries like the US and Japan, which made its way into India. However, with interest rates on their way up, particularly in the US, this easy liquidity is set to be squeezed. Does that mean the joy ride is over?

“A large number of startups will find it difficult,” said Ruparel of Indian Angel Network. “[But] an investor will always look for good opportunities. A good company is not only about growth. Problem-solving products and excellent entrepreneurs will always find takers.”

The confidence of Indian startups is also visible in their trajectory. Earlier, startups built products meant for the US and other western markets. Then came the big play with the likes of Swiggy, PayTM, Byju’s and the likes, where entrepreneurs built products for the Indian market and scaled them up successfully. And now, Indians are building products for the global market, be it fintech, space or defence.

“We have the potential to become the hub for the global startup ecosystem—we are diverse, large in terms of land space and demography, and we have the buying capacity,” said Vikram of IvyCap. “These are great ingredients for startups to come here and set up businesses.”