Information is power. And, the battle playing out between Big Government and Big Tech is to control that power. While the collateral damage of this tussle could be your freedom of expression, the advantage may well belong to a bunch of upstarts—India’s up and coming desi social media players.

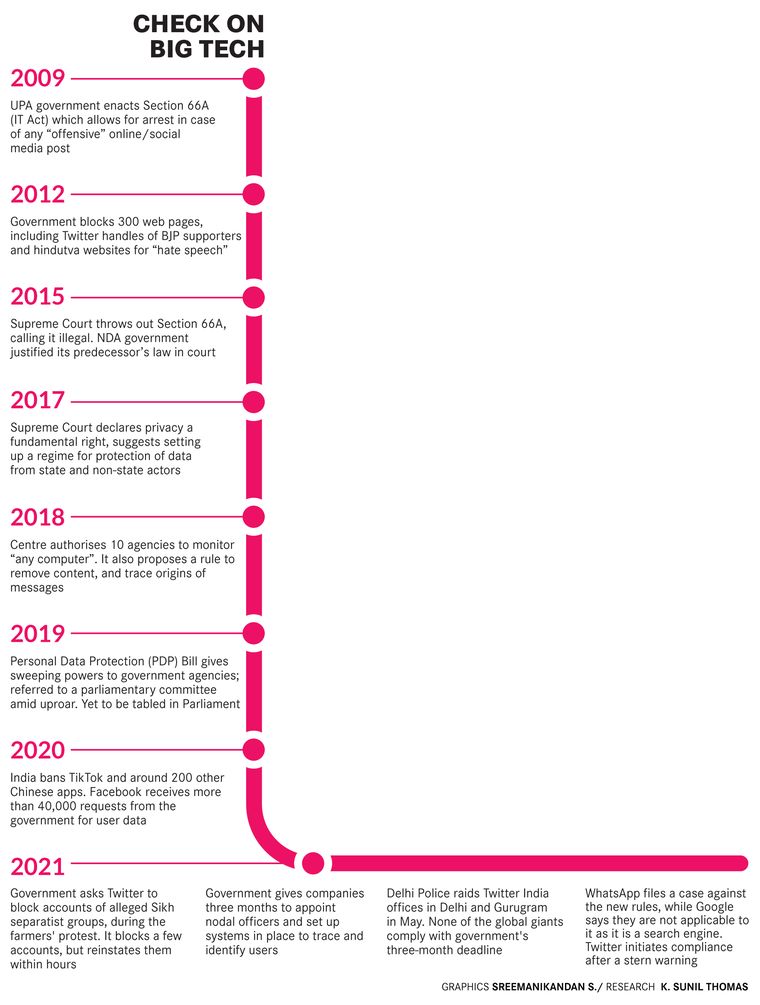

Though there have been many attempts by the government over the years to muzzle social media, intermediary rules that came into effect after a three-month grace period two weeks ago are the most lethal yet. They make it mandatory for social media companies to appoint nodal officers to take down posts that authorities find objectionable, and trace the origin of messages on services like WhatsApp.

“The government is committed to ensuring the right of privacy to citizens… but no fundamental right is absolute,” said IT Minister Ravi Shankar Prasad. “The rule to trace the first originator of [a] message is required for prevention, investigation or punishment of very serious offences.”

But privacy activists are not convinced. “Big tech like Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, WhatsApp and Google often make terrible policies and decisions that harm millions of Indians… [but these] rules do not fix these issues and end up harming your rights,” said Apar Gupta, executive director of Internet Freedom Foundation.

WhatsApp promptly filed a case against the new rule, alleging it violated the privacy of its users, while Twitter announced it would not “compromise on freedom of expression and privacy of its users”. The company, already in the crosshairs of authorities for its refusal to remove some posts that the government found ‘incendiary’ as well as for the ‘Toolkit’ controversy, has now been given a strongly worded ‘last warning’ by the IT ministry. To further muddy the waters, Google claimed in court that intermediary rules did not apply to it as it was a search engine and not social media.

Make no mistake. With 60 per cent of Indian voters having at least two social media apps and an average Indian spending 2 hours 36 minutes every day on social media, the fight is not just a government vs big company one; it is a battle for control of your hearts and thoughts.

The advantage could be to the domestic social media ecosystem that has risen up in recent months. Interestingly, most local social media apps had complied with the new rules within the deadline, unlike their global rivals. Said Aprameya Radhakrishna, CEO and co-founder of Twitter’s desi clone Koo: “Complying with the new guidelines by the government within time clearly shows why it’s important to have Indian social media players thriving in the country.”

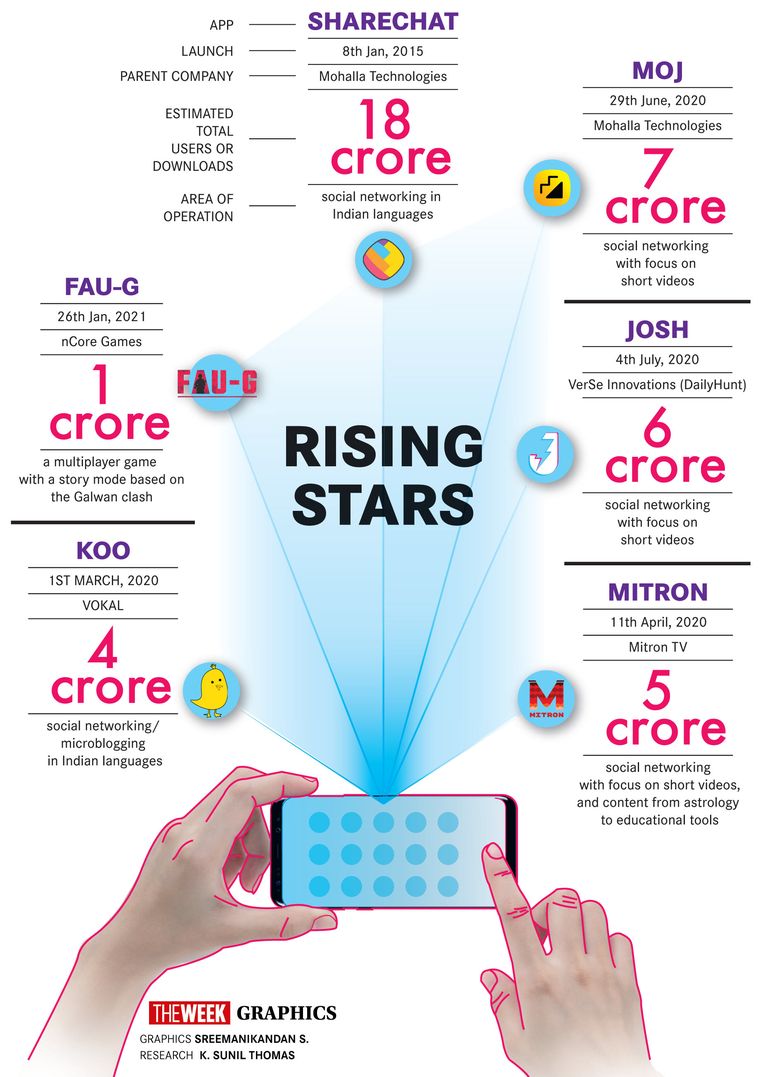

A blueprint already exists. The trickle turned into a torrent the last monsoon after the government started banning Chinese apps. The ban on the wildly popular TikTok, which had acquired 16.7 crore users in India in a short time, opened the floodgates for swadeshi social. Said Umang Bedi, founder of VerSe Innovation, which runs the leading news aggregator DailyHunt: “In the first three days after the Chinese app ban, we noticed a lot of DailyHunt users downloading short video apps. We realised that there was a real need around short-form entertainment.” VerSe launched its own short video app, Josh, in a few days. Nine months later, Josh has 9.4 crore monthly users.

The gold rush has seen many domestic short video apps suddenly burgeoning in popularity. Moj, a short video app from desi social media platform ShareChat, amassed one crore downloads in just one week after the TikTok ban. Similarly, Roposo, another short video app that was languishing in the corners when TikTok ruled, claims to have crossed five crore downloads.

“We have seen the market flourish as short-form video apps offer a platform for the audience to create content to showcase their talent and view their opinions,” said Shivank Agarwal, co-founder & CEO of Mitron TV, a short video app that was launched before the TikTok ban, but has since seen its downloads cross 5 crore in less than a year.

While the short video space is a lucrative one, attention has also been on other modes of social media. Way before China’s Ladakh incursion, the irrepressible Baba Ramdev had floated Kimboh as a desi alternative to WhatsApp, in 2018. But it was taken down by Google PlayStore because of software security issues. It later reinvented itself as Bolo Messenger.

While the ban on PUBG directly led to the spawning of a desi alternative in FAU-G, efforts to replicate Twitter’s microblogging model has been on overdrive. Prime Minister Narendra Modi himself endorsed Koo after it won the government’s Atma Nirbhar App Challenge, and a flurry of VIPs have got on to this platform. It also won Google PlayStore’s ‘Best Essential Daily App’ award for 2020, and Radhakrishna is aiming 10 crore downloads “by the end of the year”.

Serial entrepreneur Radhakrishna had earlier launched the local cab aggregator TaxiForSure (it was sold to Ola for around Rs1,500 crore) and Vokal, a site where users can ask doubts, and get answered in local language audio. “Our answering community asked why only answer, why could not we say what was on our mind. The first thing that came to my mind was that there were already products for that. Then we realised that the existing microblogging sites were all predominantly in English. So, we thought let’s start one for Indian languages.”

The opportunity, it seems, is in the language. Said Jehil Thakkar, partner and leader (media and entertainment) at the consultancy firm Deloitte India, “English internet users have already adopted certain apps and will continue to stay with them. Getting people to transition is always going to be tougher than capturing white space, which presently exists in the Indian language social media space.”

The mass adoption of smartphones in the hinterland and dirt cheap data plans have transformed the demographics of internet users in India. From being predominantly English-speaking and urban a few years ago, around 40 crore of the roughly 60 crore netizens are now local language users and spread across smaller towns and villages. This is expected to rise to 80 crore by 2024.

“People may study English as an aspirational language, but even in a tier 1 city, forget tier 2 and 3, there is a lot of depth of local language use. Indians talk, denote their feelings and like to get entertained in local languages. Their pranks, greetings and their dreams are all in local languages,” said Virender Gupta, co-founder of VerSe.

The scope of growth in the local space has seen many of these upstarts bagging generous funding from venture capitalists. While DailyHunt has been the cash cow of VerSe for years, the latest two rounds of funding were meant for Josh. Investors included Google, Microsoft and the sovereign fund of Qatar. ShareChat and its short video social media platform Moj got around Rs3,700 crore funding from Tiger Global, Twitter and others, which pushed the company into the unicorn club.

“We are impressed with the team’s understanding of these rapidly evolving technologies and its ability to execute quickly, and we are excited to partner with them as they continue to build a great company,” said Scott Shleifer, partner of Tiger Global. The American investment fund has been super aggressive in India this year, investing in many desi startups.

The ‘swadeshi’ tag of these apps, however, is open to interpretation. Investigative reports claim that Twitter clone Tooter is a re-packaged version of the American far-right site gab.com, right down to quoting American laws in its privacy policy and terms of service, while Mitron is alleged to be a reworked version of an app made originally by a Pakistani company. Koo, for all its nationalist proclamations, was left red-faced when its Chinese backers were revealed, leading to their exit a few months ago.

Yet, in the end, what would matter more than bans and the government diktats would be how much the Indian firms can rise up to the market opportunities and challenges. And if they can take on the world. For the moment, though, the desi players are shying away. “First, I think, it is very important to go deep into India and conquer that,” said Radhakrishna of Koo. “We are building a very large digital media platform out of India to serve the rest of the world eventually,” said Bedi of DailyHunt.

The global biggies, meanwhile, are upping their game. Instagram rolled out its Reels feature right after the TikTok ban, and the short video feature seems to be the focus of its algorithm now. Google and Facebook have rolled out additional features in the past months, including increased Indian language support. “International companies operating in India are aware of the market opportunities. We are the second biggest market at least in numbers, so I see them investing in products and content around the Indian language space,” said Thakkar of Deloitte.

The desi trailblazers are not too worried about their home turf, though. Bedi calls it a “distinct value proposition for Bharat”. “What Indian companies can do in addition to great tech is to identify the culture of India and bring that to the forefront to drive engagement.”

“Global players often find it difficult to localise based on region specifics,” chips in Akshay Saini, CEO & co-founder of Tring, a social networking site to engage with celebrities. “Specific features should be added swiftly by domestic companies based on local requirements, as the global players may not be agile to quickly customise for local requirements.”

Gupta said Indian apps did not ape global giants. “We have figured out our own secret sauce!” he said. It’s going to be spicy, with myriad local and international flavours going into the mix. The battle for India’s eyes, hearts and minds has just begun.