ABC may sound as easy as 1,2,3… but not when you are Narendra Modi, and ABC forms a crucial pivot on which you are basing your blueprint for the future of India’s economy.

The prime minister’s penchant for catchy acronyms is well-known, and the business and financial sectors have come up with a new one, which they feel will be the focus area of the upcoming budget—ABC, or ‘Anything But China’. “I feel the budget should cash in on the ABC movement,” said Gaurav Bhagat, business coach and founder of GB Academy. “As more and more global companies look at sourcing from India, the budget should incentivise companies that are making capital expenditure.”

Given the ravages of the pandemic, the budget that Finance Minister Nirmala Sitharaman will present on February 1 needs to attract money—a lot of it—in the form of investment, and ‘nudge’ citizens, companies and foreign investors to spend big. The wish list is clear, and long. “The budget is expected to give a roadmap of fiscal consolidation as we had a revenue shortfall and had huge expenditure because of the lockdown,” said Syed Zafar Islam, Rajya Sabha member and the BJP’s expert on economic affairs. “These are also industry expectations. Many (also) expect some announcements on the demand side, as many (of the earlier) announcements were on the supply side.”

The rope trick

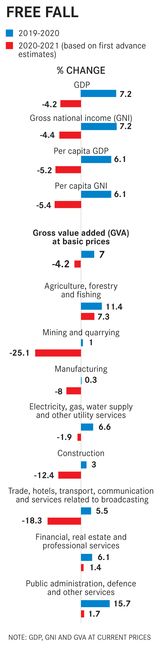

His eighth Union budget will be a tall order for Modi and his sparse exchequer. India’s economy is officially in recession, with contraction in the first quarter during the lockdown at a whopping 23.9 per cent. The pandemic has clearly affected India more than most other major economies. The budget deficit is estimated to be above 5 per cent (3 per cent is the ideal permissible limit). Add an additional deficit of 4.5 per cent, if you count in the precarious economic status of the states. Core sectors’ output is yet to revive, and crores of people are still suffering from the aftermath of the pandemic, ranging from job losses to salary cuts. Individuals and businesses have both tightened their purse strings, while industry captains, even those from sectors like automobiles and electronics that saw robust pickup during the festive season, are worried whether it was real recovery or just ‘pent-up demand’.

Politically, Modi has a tricky tightrope to walk. All his key constituencies have felt the pinch of the pandemic. Assembly elections in West Bengal, Tamil Nadu, Kerala and Assam are up in three months. Bengal is particularly crucial for the BJP’s long-term political plans.

It has not helped that many of Modi’s pet projects, especially the agriculture reforms, have been challenged. As an interim measure, the Supreme Court has stayed the implementation of the farm laws. Modi had batted firmly for these laws aimed at opening up the sector to private players. The budget may try to allay the fears of farmers by increasing the payout under the PM Kisan programme.

But the need of the hour, farm bill or not, is to push growth. And the solution?

Money, money, money

“There is a lot of spending to be undertaken, but the kitty is extremely limited. So, whatever spending the government does has to have a force multiplier (effect) on private investments,” said Arindam Guha, who leads the government and public services practice in Deloitte India.

For instance, while everyone agrees that infrastructure (from roads and urban facilities to power, health and education) will be where spending could have the best trickle-down effect, a look at the National Infrastructure Pipeline shows that the government granted just 04.5 lakh crore this financial year, while the total proposed spending till 2025 was 0110 lakh crore. Going by this, it is clear that the government can at best afford just 25 per cent of the total cost (state governments are supposed to spend 20 per cent, though that is highly unlikely in the current conditions). “There is still a 60 per cent gap in funding. That is what we expect the budget to address,” said Guha.

This is where ABC comes in. The budget can provide a roadmap for infrastructure spending that can attract money from not only private investors, but also sovereign and wealth funds of foreign governments. And, if you need to push ABC, investment in attracting global manufacturers could sow the seeds of future recovery. “Infrastructure has to be scaled up,” said Guha. “Logistics and utility costs in our country are higher than in China or Vietnam. No country is going to sacrifice its global competitiveness to invest in India. We need last mile connectivity, logistics parks, port and airport infrastructure and facilities for trade.”

Economist Sethurathnam Ravi, former chairman of the Bombay Stock Exchange, said the budget would focus on capital, because growth could not happen without capital expenditure. “All FDI limits (including insurance) will be revisited so that foreign capital comes in. And a ‘bad assets bank’ could help in making the financial system robust again,” he said.

Aniket Doegar, CEO and co-founder of Haqdarshak, a platform that links people to welfare schemes, wants the government to increase spending without worrying much about the fiscal deficit. “For the next few years it is important that the central government not only matches but also doubles up its spending on key programmes, (including) increase in government spending on social security, especially health.”

Yet, Sitharaman will no doubt look for ways to augment the coffers. The easiest way will be disinvestment of public sector entities, including monetising the government’s shares in banks. The move towards setting up a ‘bad bank’ where loans and non-performing assets are parked so that banks and financial institutions become attractive to investors could be seen in that context.

However, she could face many a stumbling block. The political opposition would be vociferous, and there would be the long list of asks from the BJP itself. In fact, the party has collected budget recommendations and given them to Sitharaman. “Inflation is an issue which affects the middle class. The middle class needs some incentives to increase investments,” said Gopal Krishna Agarwal, the BJP’s economic affairs expert. “Raw material costs are running high; that need to be addressed to help the MSME sector. Even some of the sections within the unorganised sector also needs support.”

Gentle nudges, in the form of financial instruments or affordable housing, to lure the middle classes to invest their money could also be on the way.

Nudge

Ironically, big schemes and policy announcements from the government have come from Modi himself, outside the budget. And the budgets subsequent to such announcements have made a case to nudge people to adopt those choices. This ‘nudge theory’ draws from the behavioural economics popularised by Americans Richard Thaler and Cass Sunstein. Thaler received the Nobel Prize for this theory. It is a political and behavioural economics concept which propounds indirect suggestions as a way to influence and change the behaviour and decision-making of people. It has been adopted at the international level by the United Nations and World Bank, and has influenced politicians and decision makers. Countries like the UK, Germany and Japan have ‘nudge units’ at the national level.

“Nudge policies gently steer people towards desirable behaviour even while preserving their liberty to choose,” said the 2019 Economic Survey. In the 2020 budget, Sitharaman gave tax payers a choice to adopt a new regime, which was a nudge towards a single slab tax structure, but they had to give up available exemptions like savings on housing loans and provident fund. What she had done was to nudge the country to move towards an era where there are no exemptions.

That nudge has been the government’s guiding principle as it brought in agriculture reforms. Here the farmers were given a choice to sell their produce to anyone in the open market. This nudge would have allowed the government to withdraw from grain procurement, and thus unbundling the mammoth Food Corporation of India.

The behavioural economics paid the government dividends as it led to success of programmes like Beti Bachao Beti Padhao and Swachh Bharat. A recent University of Cambridge study found out that India used nudge theory across 14 key policy areas to influence people’s behaviour, including government employees, health professionals, manufacturers and food suppliers, to help fight Covid-19 through the prime minister’s appeals.

Can we expect more reforms, gentle nudges towards structural changes in the economy?

“The government is already undertaking many reforms,” said Agarwal. “The government is working on industry-related policy, retail trade, e-commerce, logistics policy, but all these things happen at the ministerial level. There may not be reform announcements in the budget, but as far as disinvestment of PSUs is concerned that may happen as part of the reforms.”

Islam said the government had indicated that it would continue to undertake reforms. “More reforms and legislation have been undertaken in the last few months. This will continue. PLI (production-linked incentive) scheme is a very good policy reform. Labour reforms and privatisation of PSUs will continue,” he said.

What remains to be seen is what policy or scheme will Sitharaman announce that would act as a subtle push towards a particular outcome. The finance ministry had linked its additional financial assistance to the states if they undertook three out of the four reforms—One Nation One Ration Card, ease of doing business reform, urban local body and power sector reform. This nudge worked for some states, especially those ruled by the BJP, that were desperately looking for some additional bucks.