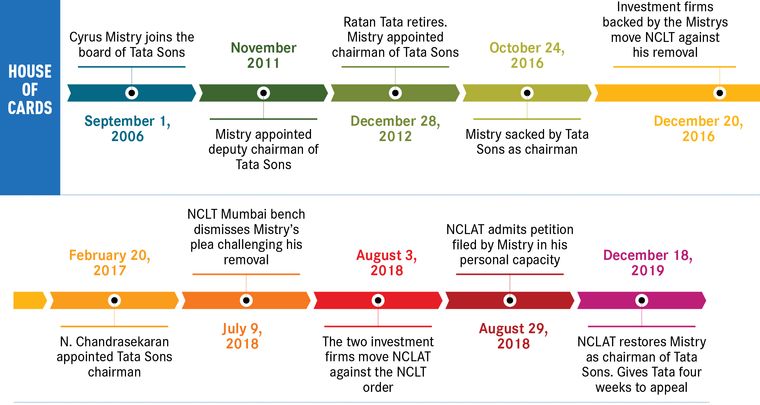

In its 150 years of existence, Tata Group has had only seven chairmen. But that was not the only reason many people were shocked when Cyrus Mistry was removed from the chair on October 24, 2016. Mistry was handpicked by his predecessor, Ratan Tata, and propped up by the clout his father, Pallonji Mistry, carried in Bombay House, the Tata headquarters. The Mistrys own an 18.4 per cent stake in Tata Sons, the holding company of Tata Group.

Mistry waged a legal battle against his removal, which was widely seen as an attempt to prove a point rather than out of a desire to get back the chair. On December 18, 2019, he secured a major victory when the National Company Law Appellate Tribunal ruled that the actions taken against him were illegal and he should be reinstated as the chairman of Tata Sons. Tata was given four weeks to comply with the judgment, but was ordered that Mistry be reinstated as a director immediately.

It came as a surprise, but people close to Mistry said it was justice done. “For the Tata Sons board members (the NCLAT judgment is a) devastating commentary on their illegal, unethical and spineless behaviour,” Nirmalya Kumar, who was a member of the group executive council set up by Mistry and head of strategy at Tata Group, told THE WEEK. Soon after Mistry’s removal, the council was disbanded and Kumar was asked to leave.

Though Tata Sons blamed the poor performance of the group companies and declining dividends under Mistry for his removal, Kumar said the truth was far from it. It was “corporate governance, transparency and the insecurity of Ratan Tata, as he felt some of his decisions being reversed and that would make him look bad in legacy,” he said. During Ratan Tata’s tenure, the group had made a global push with acquisitions like Tetley Tea, Jaguar Land Rover and Corus Steel. When Mistry took over, he focused more on profitability, than on big-bang acquisitions.

Mistry’s counsel Aryama Sundaram said that the issue was not performance, but Mistry’s insistence on management transparency and shareholder rights. “The company should be a board managed company, which is working for the welfare of all stakeholders, not just for the benefit of the trusts who are the majority shareholders of Tata Sons. That was the whole purpose of corporate governance and Mistry was insisting on it,” he told THE WEEK.

The battle was also about perceptions, and the judgment will cast shadows on a group that is known for its lofty principles. “There are various issues that are raised here, including the conduct of procedures in board meetings; how a non-board member intervened in a meeting; oppression of minority shareholders,” said Shriram Subramanian, managing director of InGovern, a Bengaluru-based advisory firm.

Apart from restoring Mistry as executive chairman of Tata Sons, the NCLAT also termed the conversion of Tata Sons from a public to private company illegal. Though Tata Sons was initially a private company, after the insertion of Section 43A (1A) in the Companies Act, 1956, on the basis of average annual turnover, it assumed the character of a deemed public company from February 1, 1975. Under Companies Act, 2013, there is no automatic provision for conversion of a public company into private and vice versa. The company must file an application before the tribunal to do so. The NCLAT observed that no such application had been filed by Tata Sons. Sundaram argues that Tata Sons’ intention was to “get away from corporate governance, because under the new Companies Act, there are a lot of rules with regard to public limited companies.”

The tussle is far from over, as Tata Sons is likely to challenge the verdict in the Supreme Court, seeking an immediate stay on the order. “It is not clear as to how the NCLAT order seeks to overrule the decisions taken by shareholders of Tata Sons and listed Tata operating companies at validly constituted shareholder meetings,” said Shuva Mandal, group general counsel of Tata Sons.

Meanwhile, the Registrar of Companies has moved the NCLAT, seeking an amendment to the order and removing the word illegal on the conversion of Tata Sons from a public to a private company. The matter will be heard in the first week of January.

The NCLAT’s judgment terming Mistry’s removal as executive chairman as illegal also makes the appointment of his replacement, N. Chandrasekaran, illegal. This raises questions about the validity of the many decisions taken by Chandrasekaran as chairman. Since his appointment in February 2017, he has been working on simplifying the group structure into ten business clusters. As a result, Tata Group companies have been working closer with each other.

Stock markets largely shrugged off the verdict, with shares of most Tata Group companies gaining ground. Tata Consultancy Services and Titan, two companies that account for a large chunk of Tata Group’s market capitalisation, have gained around 3 per cent and 4 per cent, respectively, since the verdict came. The performance of other Tata Group stocks has been mixed. Tata Steel and Tata Chemicals gained 5 per cent and 2 per cent, respectively. But Tata Motors, Tata Global Beverages and Tata Power declined 2 per cent, 3 per cent and 0.5 per cent, respectively.

“The belief among investors is that the core decisions taken by Chandrasekaran are in the interest of all the shareholders and therefore unlikely to be reversed even if the Supreme Court upholds the NCLAT order,” said Mayuresh Joshi, head of equity research India at William O’Neil and Co.

The NCLAT verdict was a bolt from the blue. And the Mistry camp is celebrating it as a victory for corporate governance. But, the battle is not over yet, and the Supreme Court will decide who gets to control the salt-to-software behemoth.