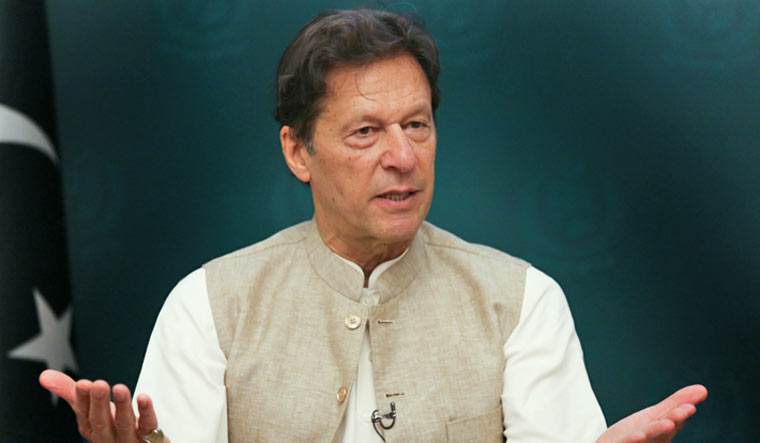

The quote about old Prussia - that it was not a country with an army but an army with a country - is true about Pakistan today. Their first national security policy, a redacted version of which was released by Prime Minister Imran Khan who has also written the foreword to it, reinforces the truism.

But then, we in India don't have much to brag about. Despite repeated attempts to draft one, India still doesn't have a national security doctrine. Pakistan has one, approved by the cabinet last month, a redacted version of which was released on January 14.

Drafted by a committee headed by National Security Adviser Moeed Yusuf, the document, which will be reviewed every year and by every new government (much like the Indian president's address to Parliament), reinforces most of what India's strategic thinkers have been saying about Pakistan - that the country continues to be obsessed with India. India is mentioned more than any other nation - 16 times to be precise in 62 pages - with Jammu and Kashmir dispute being mentioned as the “at the core of our bilateral relationship”, something which India does not agree with.

A separate section on Jammu and Kashmir asserts that “Pakistan remains steadfast in its moral, diplomatic, political, and legal support to the people of Kashmir until they achieve their right to self-determination guaranteed by the international community as per United Nations Security Council (UNSC) resolutions”. Though India's actions of August 2019 are denounced, surprisingly there is no call being made on India to restore the special status of Jammu and Kashmir.

The document does recognise that “the most acute form of efforts to undermine stability and national harmony of a society is terrorism.” The Indian leadership might remain sceptical about the Pakistan's protestations over it, but the document does reveal the deep discomfort that lies within the Pakistan state about the Frankenstein monster it has created and is now forced to go to bed with. “The employment of terrorism has become a preferred policy choice for hostile actors in addition to soft intrusion through various non-kinetic means,” says the document. “Terrorism is also being used to disrupt and delay development initiatives.” India would dismiss it as the devil quoting the scripture, but the document claims that “Pakistan pursues a policy of zero tolerance for any groups involved in terrorist activities on its soil”. As former deputy chief of the Indian Army, Lt-Gen. C.A. Krishnan (Retd) observed, “The self-congratulatory statements indicate that Pakistani is not likely to change its approach towards terrorism.”

The document has been made use of by its authors to draw international attention to domestic developments within India. “The rise of Hindutva-driven politics in India is deeply concerning and impacts Pakistan’s immediate security. The political exploitation of a policy of belligerence towards Pakistan by India’s leadership has led to the threat of military adventurism and non-contact warfare to our immediate east.” There is concern expressed over “growing Indian arms build-up, facilitated by access to advanced technologies and exceptions in the non-proliferation rules...”

All the same, the authors have been cautious not to name or blame India's hand - as is wont to by certain fringe elements within the Pakistan security establishment - behind certain terror threats faced by the Pakistan state. On the contrary, it does protest to a deep desire for peace with India. Yet it accuses India of harbouring “hegemonic designs” and, for a document that is supposed to be a vision statement, resorts to raising petty tactical-level accusations such as “ceasefire violations” on India. As former Indian Coast Guard chief Prabhakaran Paleri, who has been advocating a national security policy for India that is more than mere military security, observed, “This is a very amateurish document, as if prepared by a junior military officer, and is more a wish list than a pragmatic strategic policy based on which a definite governance intervention can be modelled.”

Over the last seven-odd decades, Pakistan had kept its security policy tied to its strategic alliance with the United States. Even after most of the western military pacts such as SEATO and CENTO were disbanded, Pakistan had remained the keystone to the US's central Asian and south Asian strategic policies. Thus even at the height of the ideological cold war, Pakistan could, through deft diplomatic manoeuvres, maintain cordial ties with both the capitalist west and the communist China, and could even dramatically effect a change in the global strategic order by facilitating a rapprochement between the two.

Pakistan still seems to have hallucinations over that stellar role, despite its relations with the United States having come under severe economic and strategic strain in the last few years. Pakistan and the US share a “long history of bilateral cooperation”, says the document. “...Our continued cooperation…will remain critical for regional peace and stability”. At the same time, the policy also says that “Pakistan does not subscribe to “camp politics”, apparently referring to the new 'cold war' that seems to be breaking out between the US and China.

One can see the beginning of a recognition that “economy is its main national security challenge,” pointed out Lt-Gen. Krishnan. All the same “document reads more like a national aspiration document. A good first step”.

The authors of the document seem to be miffed with the US attempting to narrow down its relations with Pakistan to its role in combating terror. “Communicating Pakistan’s concerns to policy-makers in Washington while seeking to broaden our partnership beyond a narrow counter-terrorism focus will be a priority,” says the document.

The other major departure from Pakistan's traditional diplomatic world view is the relatively little space devoted to the Middle East and the Islamic world. Ever since its loss of the eastern arm in 1971, and its assertion of Islamic identity during the Zia-ul Haq days, Pakistan had been putting a premium on its ties with the Persian Gulf states. But they hardly find a mention in the document, except once or twice.

Despite the strong strategic bonds that are being built with China in the recent years, the authors have taken care not to portray Pakistan as a satellite of China. “Pakistan’s deep-rooted historic ties with China are driven by shared interests and mutual understanding”, and that the ties with Beijing are based on “trust and strategic convergence”. The China-Pakistan Economic Corridor comes in for special mention as a “project of national importance”, which is “redefining regional connectivity and providing impetus to Pakistan’s economy”. As Lt-Gen. Utpal Bhattacherjee (Retd) observed, “For a long long time Pakistan national security policy was based on three As - Allah, America and Army. Since the 1970s there has also been a C - China. The C is now looming larger.”

Observers in India are largely sceptical about the protestations of peace made in the document. “Perhaps, all of it is to obtain international support to its economy, which is at the rock bottom,” said Col. S.C. Tyagi, who had worked closely with the National Security Council secretariat. “What's a complete change in this paper is that it is disengaging from the US and has embraced China for sure which doesn't augur well for others.”

Paleri flags several issues in the document. “The objectives are missing,” said he. “It is also time-limited - 2022-26 which is very short for a policy. Policies are not time-constrained, especially so for an NSP. The policy doesn't say it won't have wars with India. Decision on war is not within the control of governments but the controlling forces. In cases like India or the US the controlling forces are the governments. For Pakistan, the controlling forces are multidimensional - internal and external. The government is not part of those. My ultimate take is India should not get carried away with this. Just turn a blind eye, and carry on without getting distracted or playing Charlie Brown.”