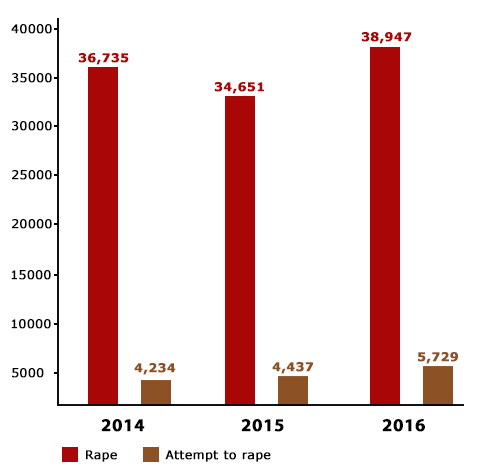

More than 40,000 rapes are reported in India every year. With every reported case, there are intense calls for tougher laws, but none of that ends in fruition. National Crime Records Bureau (NCRB) data shows that 96 per cent of rape victims in reported cases in India knew the offenders. The victims in these cases fall in the age group between infancy and 60 years, in most cases, putting India in quite a dangerous situation.

Rape is the fourth most common crime against women in India. And people are increasingly becoming immune to rape stories—something the media always feared.

“I believe that media is almost tired of reporting violence in India. Rapes, lynching, torture is being reported all the time. It's almost like you have to run a torture report, like the weather report,” Shiv Visvanathan, a Delhi-based social scientist said to the BBC.

We are now entering a state of “rape-tolerance”, where it is accepted as a household phenomenon and people are beginning to brush it past them. A journalist, who has been covering the incident in Kathua since January, says that he had been telling his colleagues (who work for Delhi-based news networks) to report on the crime and its aftermath.

“When some of the reporters approached their offices in Delhi to tell them about the incident, the feeling was that the inauguration of a garden of tulips in the valley was a better story than the rape and murder of a girl,” said Sameer Yasir, an independent Srinagar-based journalist told the BBC.

A large number of rapes go unreported. The willingness to report rape cases has increased in recent years after some rape cases got widespread media attention and prompted angry protests.

“Whenever there is a murder or rape case involving a female, in your head, you have a checklist as to whether the story qualifies to be reported or not,” former Times of India reporter Smriti Singh said in a Columbia Journalism Review report.

Today, netizens have access to instances of barbaric rapes in India's recent history. Sadly, they simply share the story and make proclamations on the social platforms. Most are content with a click of a button—“feel good activism”—and nothing more. But recently, a rape and murder led to the biggest demonstrations in years, with levels of anger and revulsion that India has not seen since perhaps the brutal “Nirbhaya” gang-rape case in 2012.

A survey by Human Rights Watch projects more than 7,200 minors (1.6 in 100,000) are raped each year in India. Among these, victims who do report the assaults, are alleged to suffer mistreatment and humiliation from the police. Of the countries studied by Maplecroft on sex trafficking and crime against minors, India was ranked the seventh worst.

A 2017 report by Global Peace Index had claimed India to be the fourth most dangerous country for women travellers. Rape cases against foreigners have led several countries to issue travel advisories that “women travellers should exercise caution when travelling in India even if they are travelling in a group; avoid hailing taxis from streets or using public transport at night, and to respect local dress codes and customs and avoid isolated areas”.

In February 2017, the ministry of health and family welfare unveiled resource material relating to health issues to be used as a part of a nationwide adolescent peer-education plan called “Saathiya”. Among other subjects, the material discusses relationships and consent. In 2017, 2,049 rape cases were reported as opposed to 2,064 in 2016.

Rape has been used as a weapon, often during wars wherein victorious soldiers would undo and shatter the enemy women. Recently, certain rape cases were used as political weapons—something that usually diverts attention from a burning issue. In the present situation, the moral compass of India is skewed, and the only way we have before us to tackle such incidents is through a broken system.

The new ordinance on death penalty for child rapists unde the Protection of Children from Sexual Offences Act (POCSO) comes as a ray of hope. Now, what needs to be ensured is that justice is served to victims on time. Recent reports suggest new fast track courts would be put up just for the purpose and that the law would be enforced effectively.