In a recent paper published in the Indian Journal of Social Psychiatry, titled 'Psychology of Misinformation and the Media', the authors start with a Jim Morrison quote: "Whoever controls the media, controls the mind."

Co-author Dr Debanjan Banerjee, a senior resident at the geriatric unit of the National Institute of Mental Health and Neurosciences (NIMHANS), Bengaluru, points to the section on responsible reporting of suicides, especially during disasters and for popular figures. Two theories from suicide-related literature are drawn to explain the role of media in abetting or preventing suicides.

On one end is the "Werther effect ", also called "Copycat suicides". The name is derived from Goethe's first successful book, The Sorrows of Young Werther, in which the protagonist, Werther, on finding himself enmeshed in a love triangle, assumes the only way out is by ending his own life. The popularity of the book led to a spate of real suicides when fans began to identify with the travails of the fictional young Werther. The event spawned the theory of "Copycat suicides" born out of local knowledge, repetitive accounts or portrayals of suicide in fiction, television and other forms of media.

At the other end is the "Papageno" effect, named after a character in Mozart’s opera The Magic Flute. Papageno, the bird-catcher, decides to take his own life after he loses his love. But, his attempt is foiled by three boys who enlighten him on alternatives to dying. From this operatic sub-plot, a simple theory was born that for anyone contemplating suicide or in extreme mental turmoil, the way the media reports the act can have a bearing on an individual's decision.

"It is also important to remember that media professionals themselves get affected with suicide reporting and vivid visual content, with studies showing a high prevalence of insomnia, acute stress, depression, and complex posttraumatic stress disorder in them," write Banerjee and his co-author T. S. Sathyanarayana Rao. They direct the reader to clear-cut WHO guidelines, framed in 2017, on reporting suicides.

Making personal assumptions, holding biases, sharing "tales" and conspiracy theories, coercive questioning of the bereaved on camera and excessive emphasis on the personal life and contextual information must be avoided.

One does not need to overstate where the India media stands on the spectrum from "Werther" to "Papageno" when it comes to reporting the latest celebrity suicide case of a Bollywood star.

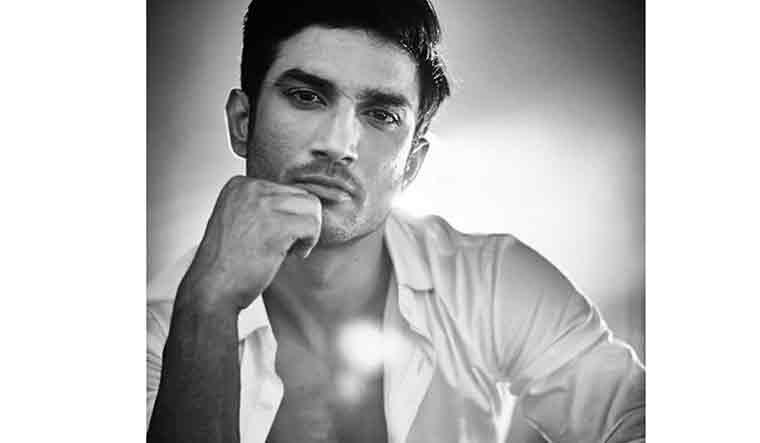

September 10 is designated as World Suicide Prevention day and one cannot help but reflect on the morbid fascination with the death of Sushant Singh Rajput which could very well have been a direct result of a mental health issue—an aspect of the case which is now conveniently overshadowed.

On 14 June, Bollywood actor Sushant Singh Rajput was found dead in his Bandra home and the cause of his death was ruled as suicide by hanging. Almost three months in and the media circus around his death is at fever pitch with all the forced suspense, intrigue and an obscene witchhunt played out in full public glare. In a recent development, Rajput's father filed a complaint to Medical Council of India against his son's therapist Susan Walker for breaking confidentiality agreements by opening up about the actor's medication for anxiety and bipolar disorder diagnosis. A crucial piece of the puzzle, a conversation around mental health in high-stakes showbiz, is now buried under high-decibel speculations around murder, conspiracy, drugs and poltical mileage.

Prama Bhattacharya, a clinical psychologist and PhD Scholar from IIT Kanpur, concedes she's never seen such overwhelming involvement of the nation in the untimely death of a celebrity and the media's efforts in keeping this fascination alive.

"I personally feel that this time a lot has been catalysed by the fact that the suicide happened during a period of nationwide lockdown. Even now, many of us are working from home, with limited social interaction in our daily life," says Bhattacharya.

"Social media thus becomes an integral part of our life. We are probably trying to make up for our social isolation by not being idle on social media and therefore having an opinion on almost everything. We are all scared of the pandemic, and the SSR case gave us something to be distracted with."

What are the mental health implications for a country on a diet of largely unfactual reporting of a suicide event and inhumane interviewing of the bereaved? What does irresponsible reporting do to the collective psyche of a nation already grappling with unrelenting public health and economic crises?

"Undoubtedly, a very negative one. Our frustration against an insurmountable crisis like the pandemic is getting rerouted in this direction where we can point fingers towards a “villain”. I wonder if this is some form of catharsis, but it worries me," says Bhattacharya.