Richa Saxena walked the hospital corridor, whispers trailing behind her—not of care or concern, but of judgment.

She was at the health centre for an abortion. A doctor herself—a third-year resident in Maharashtra—she felt each gaze sear into her. She was unmarried. The news spread quickly among the nurses.

“I was six weeks pregnant,” she says. “I was mentally prepared, but not for the slut-shaming and the expense.”

The hostility and comments from nurses and taunts from bystanders about her ‘missing husband’ left her humiliated—even within her own profession.

Richa’s ordeal mirrors what countless women in India continue to endure.

Decades of progressive policies have enabled women to strive for equality. But when it comes to control over their own bodies, do they truly have the final say?

Though abortion is legal in India with certain conditions, the emotional toll, social stigma, legal hurdles and health risks make it a tumultuous experience.

Dr Veena J.S., assistant professor, department of forensic medicine and toxicology, PSG Institute of Medical Sciences and Research, Coimbatore, recalled cases from recent years. After talking to the women involved and the investigating officers, she realised that the issue with medical termination of pregnancy (MTP) in the country was deep rooted. “One common element I could see was that all of them pleaded with gynaecologists in a government hospital for abortion; among them, two were unmarried,” says Veena. “They went to the government doctors because they could not afford private clinics. They were well within three months of pregnancy, but all doctors denied abortion, saying that it was not legal to terminate after three months. And, they pointed out, there was no clause for terminating pregnancy in unmarried women.”

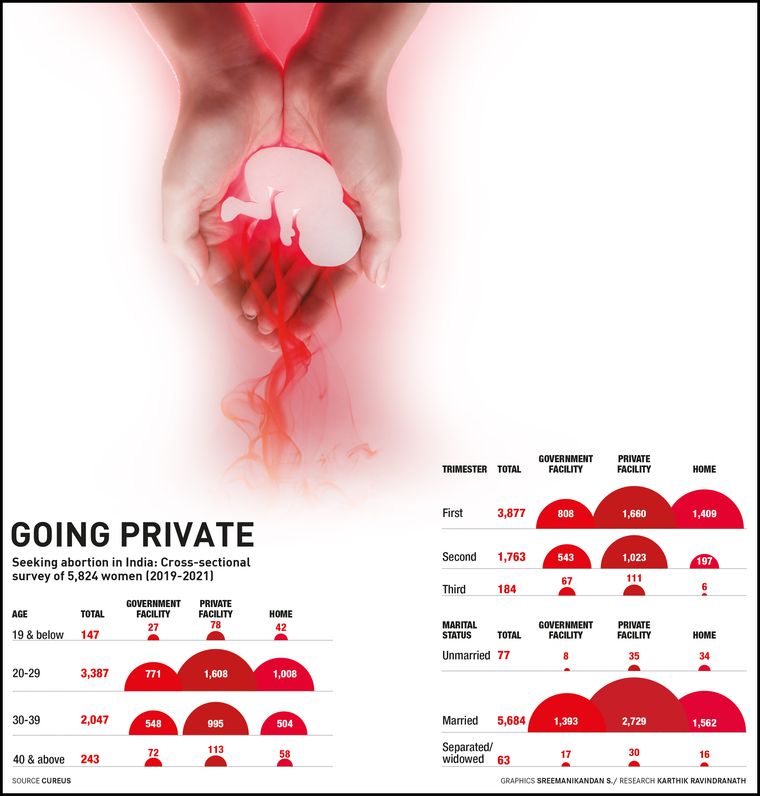

Many women look beyond government hospitals for reasons that include privacy and the wait period, with marital status, too, being a contributing factor. A study on abortion care-seeking practices in India, published by peer-reviewed journal Cureus, found that, among married women, about half of the respondents sought abortions in private facilities while over a quarter did so at home. Among unmarried women, around 90 per cent turned to private clinics or home abortions. Previous studies had reported how women hesitated to seek help from public facilities because of the requirement of repeated visits, longer waiting and confidentiality issues.

Dr Gayathri Sanjeev from Delhi had a positive personal experience of abortion at a private clinic. “I paid Rs1,000, including consultation and post-MTP care, like antiemetics (drugs that prevent vomiting) and painkillers,” she says. “The doctor never asked for my partner, nor tried to guilt me into continuing the pregnancy. I felt respected for my decision. A board in the clinic said: 'MTP/abortion is done here'.” But, she is aware that her case is an exception rather than the norm. “I get to hear from many patients from different parts of the country about the trauma they had to go through because they decided to abort the foetus,” she says.

Adding to the misery, the financial burden, including costs like post-abortion care and mental health support, puts a woman in a spot. The rates vary from place to place and can be exceptionally high if access and societal support are missing.

“I spent around Rs20,000 for the tablets and the complete procedure, including scans and consultation, left me with a bill of Rs30,000,” says Richa. “I was speechless as I know that the pills do not cost more than Rs500. Why the loot?”

The Cureus study also observed that women belonging to lower social and economic classes undergo abortions at home rather than at a health facility, and suggested that women with financial constraints avoid using abortion services from health care facilities because of direct or indirect costs.

While some medical experts feel that private hospitals take advantage of the urgency of the patient and charge exorbitant prices, a Mumbai-based doctor, speaking on condition of anonymity, justified the prices, saying that there was no ethical issue as long as the price was transparently discussed. What would be unacceptable, he says, would be charges that are not declared before the procedure. “When you look at MTP as a taboo, the prices are bound to rise,” he said. “Rather, if it is [seen as] just another procedure, the prices would come down.”

Dr Jayasree A.K., professor, community medicine at the Medical College in Kerala’s Kannur, believes cultural and religious sentiments are some of the reasons for the stigmatisation of MTP. The toxic social attitude needs to be eliminated, she says, while stressing the need for women to be able to make their choices without hesitation and have autonomy over their bodies. She also agrees that there needs to be some form of regulation in private hospitals to monitor MTP prices.

The horrendous experience of seeking MTP and the lack of accessibility often drive many to prefer dropping the foetus through unsafe methods. Religious teachings frowning upon the concept of abortion add to a lack of awareness.

While recurrent abortions may lead to infertility, the risk is higher if it is done under unsafe circumstances. Maternal mortality related to childbirth is much higher than the mortality associated with safe abortion.

What will happen if the state does not intervene to resolve the stigma related to abortion rights? “Mortality and morbidity related to lack of safe abortion will rise if measures are not taken to resolve the stigma,” says Veena of PSG, who works extensively for abortion rights. “The mental health of women will have a huge impact on future generations because, even now, child care is considered the sole duty of mothers. Another danger would be that the private sector will have more authority over women's autonomy.”

Australia-based gynaecologist Dr Joseph Johnson says that despite the liberalisation of MTP in India, religious and cultural influences, social stigma and access barriers remain significant hurdles. From a patient’s perspective, he says, India can take pride in having a progressive legal framework that compares favourably with countries like the UK and Australia, and, to a large extent, surpasses the policies of many US states. Nevertheless, access to safe and legal MTP remains uneven across the country, especially in situations when maintaining confidentiality is paramount.

“Many gynaecologists remain reluctant to offer MTP services, particularly for non-medical indications,” he says. “In cities like Kochi, only a handful of specialists offer comprehensive MTP care in reputable hospitals when the termination is sought for personal or socioeconomic reasons. This limited access has contributed to the rise of smaller clinics, which charge steep prices and operate in a largely financially unregulated manner. But one should still appreciate the fact that even in these small clinics, procedures are performed by qualified specialists.”

An earlier study on abortion care from Jharkhand, published in the Economic and Political Weekly, had observed that women who could not afford to pay for a qualified private physician sought care from unlicenced or government facilities.

“When affordability is denied, abortion service in the private sector becomes a money-minting option,” says Veena. “An abortion medicine kit, which can be self-administered and costs not more than 1,000, will change to a days-long hospital stay, minting money for the private sector. Women who cannot afford the service will be forced to approach quacks or take loans.”

While the abortion laws in India have evolved to recognise a woman’s right to choose, the ground reality is harsher. It is often a choice that comes at a steep price.