NEW DELHI

Has any other disease captured the popular imagination through movies and books the way cancer has? The characters stay with us long after the credits have rolled and we walk into the light. Hazel Grace Lancaster and Augustus "Gus" Waters from The Fault in Our Stars (2014), Sophie Ritter from The Girl with Nine Wigs (2013), Tessa Scott from Now is Good (2012)….

The books, too, have been best-sellers. Think When Breath Becomes Air by neurosurgeon Dr Paul Kalanithi and Pulitzer-winning The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of Cancer by oncologist Dr Siddhartha Mukherjee. Despite so much having been written and filmed about cancer, much remains—both stories and science.

No other condition, barring heart attacks and diabetes, feels so personal. We all know a cancer-survivor and a non-survivor. We all have a story. Sometimes sweet. Sometimes bittersweet. Mostly, just bitter.

On June 13, 2025, my brother-in-law said his final goodbye to us. A professor of electronics, he had one wish—to complete his career and retire from service. Thirteen days after he signed the college register for the last time, the non-smoker and teetotaller gave up his fight with lung cancer. From diagnosis to Friday the 13th, it took just about 18 months. You, too, will have a story, I am certain.

So, when a vaccine trial is believed to be on track to beat triple-negative breast cancer, it represents a hopeful shift in patient care—from treatment to prevention. The vaccine being developed by Cleveland Clinic and Anixa Biosciences could mark a significant breakthrough in women’s health and global cancer prevention efforts.

It was in this context that Dr G. Thomas Budd delivered the keynote address at THE WEEK Health Summit Premier, an exclusive and invitation-only event at The Oberoi, New Delhi, on November 14. The tall and soft-spoken Budd is the principal investigator of the phase I clinical trial of the vaccine.

He was joined on stage by his colleague Dr Jame Abraham, and Dr Sapna Nangia. Abraham is chair of the department of haematology and medical oncology at the Taussig Cancer Institute, Cleveland Clinic, and Nangia is the director of head & neck and breast cancer at Apollo Proton Cancer Centre, Chennai, the first such centre in south Asia and the Middle East.

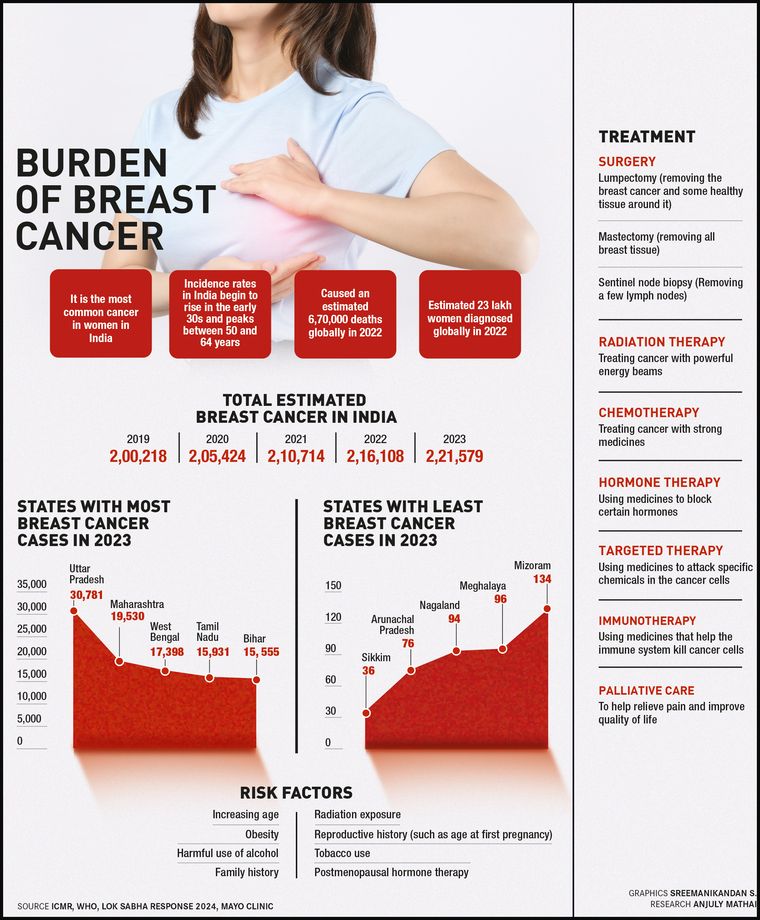

Nangia began by putting the vaccine in context for India. The vaccine targets triple-negative breast cancer, an aggressive cancer that lacks receptors targeted in hormone therapy, and this makes it more challenging to treat. “In Italy, the UK, or Germany, about 10 per cent of (breast cancers) are triple negative. While in India, that number is more than 25 per cent,” she said.

Another fact Nangia highlighted was that “Indian women have breast cancer at a median 10 years earlier”. She said: “So, if the median age for developing breast cancer in the west is 60, in India it is around 50 years. And there is a higher proportion of Indian women who may have breast cancer (around) the age of 35 or below.” All this data underscores the importance of the vaccine being developed by Budd’s team, Nangia said.

“Indian oncologists are now turning the gaze inwards and not looking only towards the west for research and information, but also examining how that research and developments are applicable for Indian patients,” she said.

She drew the audience’s attention to the BRCA1 and BRCA2 genes, which increase the possibility of having breast cancer. “Typically, they are inherited genes. They can also happen as independent mutations… So, the south appears to have more BRCA positivity than eastern India, according to one study. And one of the thoughts that was expressed was that it is because there was a Jewish presence in south India (and Mumbai).

“I think that it primarily seems to be only speculative. It could also be because there is more consanguinity in certain parts of the south. Now, one of the interesting developments that has taken place in the last many years is the development of an understanding that the genomic profile… the genes that a breast cancer has could impact their outcomes.”

Abraham then took over and quickly described the work done by Cleveland Clinic in the oncology space. During the conversation, an interesting fact emerged: the US Department of Defense (DoD) is one of the sponsors of the breast cancer vaccine. From prosthetics to QuikClot combat gauze, implants, and vaccines, the DoD has been funding research in diverse medical fields. The Covid-19 pandemic only boosted the DoD’s watchfulness over medical conditions that are not related to combat.

Budd began with characteristic humility and humour, crediting a late colleague who piloted the vaccine programme. “I must confess that I am just the dumb clinician who is doing the clinical trial that was developed by my colleague, Dr Vince Tuohy, who has now passed away. But he did get to see his vaccine given to a human being, and he was very gratified by that. He saw the first immune responses, and I think he knew that he had done important work. He was the inventor and a staff immunologist at Cleveland Clinic.”

He then explained Tuohy’s “retired protein hypothesis” with a slide that showed a man with greying hair. The hypothesis proposes that cancer vaccines can target tissue-specific proteins that are usually present only during a specific, temporary life stage.

“The idea here is that with age, we retire some proteins that are no longer needed,” Budd said. “And some of these proteins are overexpressed by tumours, often tumours (in organs) that express that protein. And these organs can have a high incidence of cancer. And the first candidate is alpha-lactalbumin, a milk protein usually made in lactating breasts.” Alpha-lactalbumin production has also been observed in women who are not lactating, but this is uncommon.

Tuohy injected mice with a highly aggressive triple-negative breast cancer and then immunised them at various times. “The immunisation was effective in delaying tumours,” Budd said. “The earlier it was given, the better it worked. But the most impressive results were in a prevention model. This vaccine in this small study in a murine model was 100 per cent effective.”

A murine model is a laboratory mouse used in biomedical research to study human physiology or disease. Then the question, Budd said, was whether it was possible to get an immune response in humans to alpha-lactalbumin? “And there were some in-vitro studies showing that, yes, indeed, it was possible.”

So, how close is the vaccine? “All we have identified so far is that we have found a dose that patients can tolerate, and we can produce an immune response. But many, many other questions need to be addressed before this can help women around the world,” Budd said.

During the audience interaction, the question that is topmost on your mind was asked: will we see this vaccine in our lifetime?

The answer came from Abraham: “I think so. I clearly think so. So many things are happening at this point. This is the time of AI and if I do not talk about AI from this platform, we are missing something. So, the vast amount of genomic data is tough for us to comprehend. Even though I deal with only breast cancer, when we look at the genomic data, we get from a patient about 30 or 40 pages of data. When you look at whole-genomic sequencing, we get thousands of data points. I believe that AI will help us read this and then really help us to understand the next steps.”