In the time it takes you to read this sentence, another new mother in India has slipped into a darkness she doesn’t understand. For every five newborns who announce their entry into the world with a shrieking cry, one new mother faces this reality. This darkness has a name: postpartum depression (PPD).

Pregnancy and childbirth are emotionally and physically demanding. They bring a hormonal swell of euphoria and exhaustion. But when that natural swirl turns into a tsunami of emotional and physical ebbs and flows that don’t seem to stop, postpartum depression is closing in.

Not every emotional struggle after childbirth is depression. Almost 60-80 per cent of women experience temporary emotional disturbance called ‘baby blues’ after childbirth. These consist of brief spells of low mood, tearfulness and irritability lasting minutes to hours. These usually subside within a week or two. But when those weeks extend to a persistent period of pervasive and intense sadness, it becomes cause for concern. One comprehensive systematic review and meta-analysis published in the WHO Bulletin found that postpartum depression affects 22 per cent of Indian mothers—nearly double the global average of 10-15 per cent.

PPD involves lack of interest in activities, anxiety and feelings of hopelessness or helplessness that continue for weeks or months. It affects mothers across five critical dimensions: physical health, psychological wellbeing, quality of life, relationships and overall mortality risk. The symptoms include excessive fatigue, feelings of worthlessness, difficulty bonding with the baby, trouble concentrating, and disrupted appetite or sleep patterns. More severe manifestations involve overwhelming fear of inadequacy as a mother, persistent hopelessness, crushing shame and guilt and, in the most serious cases, thoughts of self-harm or harming the baby.

Psychiatrist Dr Kanishka Meel observes that symptoms can also manifest as constant vigilance. Mothers may check their babies’ breathing repeatedly through the night or experience intrusive thoughts about potential harm. Families frequently dismiss these behaviours as ‘new mother worries’. Medically though, this could be a generalised anxiety disorder that might co-exist with PPD. Meel adds that while intrusive thoughts about harm are “usually unwanted and distressing, and don’t reflect a desire to act on them, they signal serious emotional suffering requiring immediate medical attention”.

Let’s contextualise this through a haunting example shared by Dr Madhusudan Singh Solanki, head of mental health and behavioural sciences at Max Smart Super Specialty Hospital Saket. It comes from his days as a resident doctor.

“I remember a case that painfully reminds me how ignoring postpartum depression can have devastating consequences,” he recalls. “A young mother was brought to our emergency department at midnight after killing her one-month-old son—a child born after 10 years of marriage—by drowning him in a bathtub.” When assessed, it became clear that symptoms had been visible but no one paid attention or sought help. “The condition gradually worsened, and she started hearing voices commanding her to kill her son, telling her he was an omen of death and destruction,” recounts Solanki.

What Solanki describes is the broader mental health landscape beyond PPD. Postpartum psychosis affects one or two women per 1,000. It is a psychiatric emergency characterised by sudden onset of delusions, hallucinations, extreme mood shifts and disorganised thinking. It typically emerges within two weeks of delivery.

Dr Smriti Agrawal, professor of obstetrics and gynaecology at Queen Mary’s Hospital, the OBGYN wing of King George’s Medical University, Lucknow, encountered a particularly alarming case of a new mother from a well-educated family. “The attendants came running to us one day saying, ‘She's trying to strangle the baby.’ We immediately rushed and realised the woman was very distraught... [and] was in postpartum psychosis.”

The dramatic hormonal changes following childbirth create the ideal conditions for mental health challenges. After delivery, oestrogen and progesterone levels plummet suddenly, impacting brain chemistry and potentially triggering mood disorders. The brain’s natural mood-regulating systems become disrupted during this transition. Oestrogen impacts serotonin and dopamine—chemical messengers that carry signals between nerve cells. Serotonin brings about happiness, calm and focus. Dopamine is linked to pleasure, motivation and reward. Progesterone influences mood processing and stabilisation.

Dr Shehla Sheikh, consultant endocrinologist at Saifee Hospital, Mumbai, adds one more hormone to the mix: prolactin. This one plays a crucial role in lactation, but also influences overall hormonal balance.

“The initial breastfeeding also triggers an oxytocin surge that stimulates the milk ejection reflex,” says Sheikh. Also known as the ‘love hormone’, oxytocin plays a significant role in bonding, stress regulation and overall mental health.

There are further complex alterations in brain chemical systems. These include dysfunction in GABA (gamma-aminobutyric acid, which helps calm brain activity), and disrupted neurosteroid production (brain chemicals derived from hormones that affect mood and anxiety).

Simply put, the brain chemicals that help with mood and relaxation don’t work as well in women with PPD. There are other hormones, too, produced by the placenta. Post childbirth, all of these fall in one mighty swoop.

“This dramatic hormonal shift affects metabolism, mood and overall wellbeing,” says Dr Chitra Selvan, consultant endocrinologist at Ramaiah Memorial Hospital, Bengaluru.

So sudden is the drop that hair, skin, bowel movement—nothing is off limit.

New disorders can be born from these hormonal changes. Thyroid-related conditions (postpartum thyroiditis) are the most common. Symptoms include weight loss, tiredness, palpitations, tremors and sleep difficulties. Later, postpartum hypothyroidism may develop, causing weight gain, fatigue, hair fall, dry skin and constipation.

“During pregnancy, all autoimmune conditions kind of pause and then right after delivery there can be a small surge in incidence of autoimmune conditions,” notes Selvan. An autoimmune condition is one where the body’s own immune cells begin to attack healthy cells. Think type 1 diabetes, wherein the immune cells attack the insulin-producing cells.

The stress response system also undergoes dramatic changes. During pregnancy, the body’s stress management system becomes overridden by pregnancy hormones. After delivery, this leaves new mothers particularly vulnerable to stress and mood disruptions as their systems struggle to recalibrate.

Dr Manish Chhabria, senior consultant in neurology at Sir H.N. Reliance Foundation Hospital, Mumbai, points out that symptoms can also manifest as postpartum headaches. These can be both a physical consequence of childbirth and a symptom of depression itself.

“Headaches, especially migraines, can be a risk factor for postpartum depression, particularly in women with a history of depression,” he says. Rapid hormonal changes and the stress of new parenthood can all contribute to these headaches. This makes careful evaluation crucial to rule out serious secondary causes.

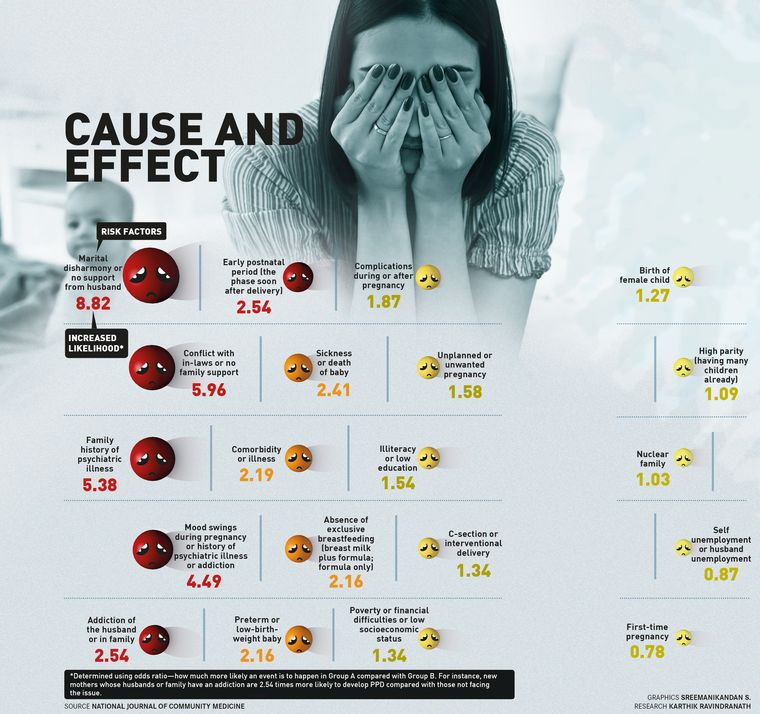

Some risk factors affect women globally: a history of major depressive disorder/s, family history of depression, ambivalence regarding pregnancy, exposure to domestic violence or marital discord, financial stressors, hormonal imbalances, thyroid issues, gestational diabetes, nutritional deficiencies and substance use during pregnancy.

There is a genetic and environmental web around PPD. Genetics accounts for 40-50 per cent of risk factors. Women with family histories of depression or bipolar disorder face substantially higher risks. About 30 per cent of women experiencing PPD will have recurrences with subsequent pregnancies.

While these universal triggers affect Indian women, our country presents unique challenges that compound these risks. The starkest among these is the birth of a female child or birth of a second female child.

Agrawal was part of a study on the reasons why women with two healthy children went in for a third pregnancy. The most cited reason was that the two elder children were girls. The second was that there was a male and a female child. The subtext: the third pregnancy was in the hope of begetting one more male child. “There are high levels of anxiety in mothers with two female children,” she says.

The societal pressure manifests in whispered disappointments, pointed suggestions about ‘trying again soon’, decreased family visits and partner distance. This isolation during what should be a celebration contributes to depression lasting months.

Agrawal often tells her patients to look around and notice that they are surrounded by women—as doctors and nurses—doing well for themselves. Yet that nudge cannot budge societal burdens.

Studies have identified lack of social and spousal support as significant contributors to PPD along with the shift of attention from mother to baby after delivery. This is particularly pronounced in urban settings where traditional support systems may be absent.

Dr Manisha Tomar, consultant obstetrician and gynaecologist at Motherhood Hospitals, Noida, highlights modern lifestyle factors: “Women with high-stress careers, those in nuclear family setups, or older mothers may be more prone…. However, currently, even those who are homemakers are struggling.”

There is a cruel bind here. Even in urban settings, we remain tethered to customs—not as they were originally imagined but twisted to our conveniences. One such custom is a period of seclusion for the new mother, originally meant as a period of rest and recuperation.

Radha Sharma (name changed), a management professional married to a techie, was banished by her mother-in-law to a mattress-less wooden cot for 40 days post the delivery of her first child—a daughter. That isolation would have been manageable but for the fact that her mother-in-law insisted that she touch the feet of every elder who came by to bless the baby. Sharma had a C-section and the constant bending caused her surgical stitches to rupture. Her husband watched on in silence. “I started to resent my baby,” she remembers. But her woes were nipped as her determined mother stepped in and took Sharma away for proper rest.

Experts point out that the joint family living may result in lack of privacy or strained relationships with in-laws, while women who migrate from rural to urban areas face isolation and unfamiliar support systems. Spousal support might also be lacking due to the conception that these are ‘women’s matters’.

Delivery complications add another layer of risk. Emergency caesarean sections, prolonged labour, excessive blood loss or neonatal ICU admissions can significantly increase a mother’s stress and trauma levels.

Dr Tripti Raheja, lead consultant in obstetrics and gynaecology at CK Birla Hospital, Delhi, adds, “Caesarean deliveries, particularly when unplanned, may create a sense of loss of control or failure, and the longer physical recovery period can compound emotional strain.”

There is also a complex relationship between breastfeeding and mental health. While successful breastfeeding can provide bonding experiences aided by oxytocin release, difficulties create their own psychological burden.

“Latching problems, low milk supply, or painful feeding can lead to frustration, self-blame and a sense of inadequacy,” points out Raheja. “Societal pressure to exclusively breastfeed can further intensify guilt, especially in women who are unable to or choose not to.”

A conspiracy of silence shrouds PPD. This is compounded by the fact that few women have knowledge about PPD. Medical awareness varies significantly across specialties. Dr Basavaraj Devarashetty, an infertility specialist and gynaecologist, estimates that “90 per cent of gynaecologists and 50 per cent of other medical fraternity” have adequate knowledge about PPD, revealing significant gaps in health care delivery. In government hospitals where most Indian women deliver, PPD is an acute challenge.

“We see all sorts of postpartum depression, but it is very difficult to detect,” acknowledges Agrawal, who has two decades plus of experience in the sector. The statistics she offers on what a typical work day for her looks like are mind-boggling. As a consultant, she sees 70-80 patients daily, sometimes managing only five minutes per patient. What she lacks in time she makes up for with her experienced intuition. “Just by eye contact and how she (the expectant or new mother) answers questions, we can judge her stress and anxiety levels,” says Agrawal. Resource constraints further complicate the situation. “A lot of times women come from far-off areas without being accompanied by relatives they can confide in.... They are often referred to us last minute, which affects (treatment) outcomes,” she adds.

The huge stigma around mental health overall keeps women from seeking help. Support groups are almost non-existent except for some online communities. Cultural expectations compound the problem. Society demands that new mothers radiate joy and appear naturally nurturing. Admitting to sadness or difficulty in bonding feels like confessing to fundamental inadequacy as a woman.

Diagnosing PPD requires a careful clinical process that goes beyond simple mood monitoring. Health care professionals start with screening tools to identify at-risk mothers, but diagnosis requires comprehensive professional assessment.

The Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS) is the most widely used screening tool—a simple 10-question self-report questionnaire specifically designed to spot depressive symptoms in new mothers.

Devarashetty explains the EPDS comprises 10 items prompting respondents to reflect on their experiences over the past seven days. “The cumulative score serves as an indicator, with a score of 13 or above signalling the need for follow-up care,” he says. The EPDS is available in Hindi and several other Indian languages, making it accessible across India's linguistic landscape.

However, no screening questionnaire can make a diagnosis on its own. Tools like the PHQ-9, Beck’s Depression Inventory, or the GAD-7 for anxiety may also be used. The actual diagnosis must be made by a psychiatrist or trained mental health professional through comprehensive clinical assessment.

Raheja describes this diagnostic complexity: “Fatigue, appetite changes, sleep disturbances, low libido and difficulty concentrating are common postpartum issues but also key symptoms of depression. I look for emotional red flags like excessive guilt, hopelessness, disinterest in the baby, or thoughts of self-harm rather than attributing everything to ‘normal postpartum recovery’.”

For many women, the first step involves psychosocial support rather than medication. Cognitive behavioural therapy and interpersonal therapy often prove highly effective, helping mothers understand and change negative thought patterns while building coping strategies.

When medication becomes necessary, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) are generally considered safe during breastfeeding. These medications work by increasing serotonin levels in the brain to improve mood.

Chhabria highlights newer treatment advances: “Neurosteroids like brexanolone, which positively modulate GABA-A receptors, have been approved for the treatment of PPD. Zuranolone, another neurosteroid, has been approved as the first oral medication for PPD.” These targeted medications offer hope for women who don’t respond to traditional treatments. GABA receptors are specialised proteins on nerve cells that respond to chemical messengers, thereby regulating brain activity.

Solanki says that treatment is tailored based on symptom severity and patient profile. It can include supportive counselling, cognitive behavioural therapy, medications, and rTMS (Repetitive Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation)—a non-invasive procedure that uses magnetic fields to stimulate brain regions. In severe cases or with psychotic symptoms, Electro-Convulsive Therapy (a medical procedure using controlled electrical currents to trigger brief seizures that can rapidly improve severe depression) provides rapid relief. Treatment duration varies from months to sometimes years.

Treating PPD requires teamwork between a range of specialists including psychiatrists, psychologists, therapists, lactation consultants, paediatricians, gynaecologists and physicians. Sometimes, social workers or support groups also play a key role, especially when there are socioeconomic or domestic challenges.

A common concern among new mothers involves antidepressant medication safety during breastfeeding. Almost all psychotropic medications enter breast milk in very low quantities. Long-term impacts on newborns aren’t well-researched due to study limitations, though no life-threatening or cognitive effects have been reported. Expert opinion tilts towards using medication when possible benefits outweigh potential side effects.

“Side effects vary among patients and are usually mild and self-limiting,” says Solanki. “[These] include appetite changes, bowel movement alterations, bloating, heaviness, sleepiness or insomnia, blurred vision, dry mouth, mild headache, dizziness, and light headedness, which usually subside after several days or with dosage or medication changes.”

For women with a history of depression, preparation begins before conception, with doctors involving mental health professionals early. Raheja emphasises the importance of routine screening. “I begin screening at the first postpartum visit, typically around six weeks, but I also keep an eye out earlier during postnatal check-ins or paediatric visits,” she says. For mothers with a history of mental health issues or red flags like lack of interest in the baby, she screens earlier and more frequently.

Post childbirth, transition periods are particularly vulnerable. Weaning, for instance, is one such risk period when there is a drop in prolactin and oxytocin. This hormonal shift, especially if abrupt, can trigger or worsen depressive symptoms.

Even contraceptive choices require careful consideration for women recovering from PPD. Raheja says she prefers non-hormonal methods or progestin-only methods initially, as oestrogen-containing contraceptives might exacerbate mood symptoms in some women. Progestin is a synthetic hormone that mimics progesterone.

The connection between endocrine disorders and PPD is significant—thyroid disorders, diabetes, or conditions like lymphocytic hypophysitis (a condition where the pituitary gland does not produce enough hormones) can all have features that mimic or worsen PPD.

Family involvement is crucial for recovery. Supportive partners and understanding relatives significantly improve emotional wellbeing and treatment outcomes. The most important step loved ones can take involves gently encouraging professional help while offering to schedule or accompany mothers to appointments.

Practical support—help with baby care, meal preparation, cleaning and errands—is just as vital. The importance of patience cannot be overstated. Recovery takes time and there will be some good days and some not so good ones.

“It is a request to all family members to show up and take responsibility for childcare and household activities, so that mothers feel supported through this challenging time,” urges Selvan.

PPD’s impacts extend far beyond mothers. As the mother’s ability to respond consistently to her baby’s needs decreases, harmful consequences cascade through crucial developmental processes.

Dr Minu Bajpai, head of paediatric surgery at Yashoda Medicity, Ghaziabad, says that it could “lead to attachment issues in babies, including lack of eye contact, limited facial expressions, difficulty being soothed and withdrawal from social interaction”. If multiple signs are noticed in an infant, especially in combination with a mother showing persistent sadness, disinterest or withdrawal, it is important to seek help. Children of mothers with untreated PPD also face higher risks of language delays, cognitive development issues, and later, anxiety and depression.

“There could be long-term consequences, including low self-esteem, cognitive and academic challenges. Children may struggle in school due to attention deficits, memory issues or lack of motivation and potential health impacts, increasing the risk of health issues like heart disease or immune disorders later in life,” says Bajpai.

However, these impacts can be reversed through early intervention and consistent, loving relationships with caregivers.

Despite significant challenges, medical professionals express cautious optimism about progress. Growing awareness over the past decade has transformed understanding of PPD from a vague concept to a recognised medical condition requiring specific interventions. It is no longer something that mothers should just be expected to get on with, as their own mothers and grandmothers did.

This awareness translates into proactive care. “It is essential to discuss postpartum depression with all expectant mothers,” emphasises Tomar. “Knowing the signs helps them understand it is common and treatable.”

Tomar shares her current clinical reality: “In two months, at least two to three mothers visit me with postpartum depression. The number has surely gone up over the years, but it is not possible to provide the exact percentage as many cases go unreported due to lack of awareness, guilt, shame and embarrassment.”

Online support groups provide platforms for women to connect with others facing similar challenges, sharing concerns and fighting isolation together. These communities, combined with professional counselling, create previously unavailable support networks.

Digital mental health tools represent promising avenues for addressing access barriers, particularly in rural areas. Telemedicine platforms can connect remote mothers with mental health professionals, while mobile applications provide screening tools, educational resources and peer support networks.

The government is increasingly emphasising digital mental health solutions, such as the Tele MANAS helpline, to improve access to mental health services, particularly in remote areas. However, successful implementation requires addressing digital literacy gaps, ensuring privacy and security and integrating these tools with existing health care systems.

Improvement in government hospitals requires fundamental changes. “More staff sensitisation, greater privacy and one-to-one interactions could help us identify postpartum depression at early stages,” suggests Agrawal. “Often, all women need is reassurance.”

The economic burden of untreated postpartum depression includes not just immediate health care costs but long-term reduced maternal productivity and potential long-term costs associated with child developmental delays.

We are a country that has put mental health on the backburner for long. Our most recent budget set aside only 1.3 per cent for mental wellbeing. Addressing PPD requires systemic interventions across multiple levels. Health care policy should mandate routine screening during prenatal and postnatal visits, ensure adequate mental health professional training and integrate maternal mental health services into existing health care infrastructure.

Educational initiatives should target not only mothers but also families, communities and health care providers. Public awareness campaigns must destigmatise maternal mental health struggles while promoting help-seeking behaviours.

Several states have begun implementing innovative approaches to maternal mental health. Community health worker programmes in Karnataka have shown promise in early identification and referral. Kerala’s integration of mental health services into primary health care has improved access and outcomes.

The message is clear: postpartum depression is real, common and treatable. As one mother who recovered from severe postpartum depression reflected: “I thought I was broken, that I would never feel love for my baby. But with help, I discovered I wasn’t broken; I was sick, and sickness can be healed.”

And for that new mother who slipped into darkness as you began reading this—she doesn’t have to stay there. In the time it took you to read this article, somewhere in India, another mother has taken her first step towards healing. The darkness has a name, but more important, it has an end.