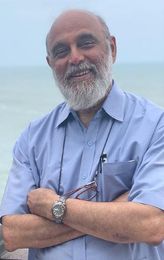

We live in a world full of labels and categories, and as we grow up we learn to fit people into these labelled boxes, even as they do the same to us. But humans are intrinsically complex, contradictory and often hard to box up and label easily. And nowhere has this been more apparent to me than watching the parenting style of my gruff, middle class, Telugu father who turned 70 on March 2. My father, a naval officer with the soul of a resigned philosopher and observer of human nature and folly.

As children, we heard him call out in loud, enthusiastic cries to not one but at least three gods, after his morning bath and evening ablutions. It always began with, “Mainu te maaf kar dey, Rabba [Forgive me, Rabba]!” And sometimes he would say, “Hey Allah, mere malik, reham karo [Hey Allah, have mercy]!” There was the Venkateshwara suprabhatam that we woke up to every holiday morning—“Kaushalya Supraja Rama Poorva Sandhya Pravartatey [Rama, son of Kaushalya, as the night turns to dawn]….” Then his daily Hindu puja. It was no wonder that my brother and I remained blissfully unaware that Rabba, Allah, and Venkateshwara belonged to three separate religions.

My father’s faith in military methods was and remains steadfast. When my brother and I misbehaved, we were punished with gruelling exercises that he remembered from his National Defence Academy days. He would improvise and adapt these to suit a two-bedroom government quarters. His favourite was to make us kneel down with our nose touching the wall. For those unfamiliar with this position, please try it—your knees will melt after a minute or so! At the end of our punishment, there were always some treats from the market for us. That is another military conviction—the troops must be well-fed at all times, even if punished.

But he was, and is, fundamentally a democratic man. Our most severe punishment was to be whacked with a rolled-up newspaper. However, we had some agency in our punishment. We got to choose where we would receive the whack. “Hand or bum?” he would ask. Most of the time our choice was bum. Somehow it made the punishment reasonable and our father less fearsome—that even when angry he was open for negotiation and dialogue, and even when guilty, we had rights.

But my father’s most out-of-the-box traits were seen when I was 10 and my mother got a full scholarship to pursue a PhD at New York University. My mother left for New York, and my father remained in India with us, becoming a single parent intermittently for four years. At the time, I did not realise how radical it was for an Indian middle class family to have the husband look after the children, while the wife pursued a career goal abroad. How wonderfully unusual and enabling my parents’ relationship was—to have been able to work through that arrangement and remain committed to each other and come back to ‘normal’ once the PhD was done. But perhaps the most wonderful quality I observed in my father as a husband was that he never made a big deal about any of it, never tried to gain praise for being a supportive husband, never acted like he had done my mother a favour nor showed off his good-husband-ness in a self-aggrandising manner. He was a feminist without trying to be one, at a time when it wasn’t cool or ‘woke’ to be a feminist.

When I left for Mumbai to follow my Bollywood dream, my father simply said: “You are an adult now, and you are going to a different city. You will have an independent life and there will be many things about your life that your mother and I will not know, nor be able to monitor. Just remember that whatever you do, you will have to look at yourself in the mirror. Every day.”

Those words grounded me, even as they set me free. And once again, my father had found a democratic way to express his parental anxiety and caution while also imparting to me my life’s most profound lesson.

Happy 70th birthday, dad. Thank you for imparting to me the constitutional principles of secularism, democracy and equality in the most out-of-the-box manner possible. I am so proud to be the daughter of such an unusual father.

The writer is an award-winning Bollywood actor and sometime writer and social commentator.