When my publishers at Aleph invited me to put together a book on words and language, I hesitated for a brief moment. A book on words (following on the heels of the successful Tharoorosaurus) was all very well, but did a serious politician really want to reinforce the image that had grown up of himself as an etymological egghead? As one journalist rather breathlessly asked me, “Your vocabulary has become the subject of memes, comedy shows and now a book! Did you ever think things would take such a turn?”

Well, no, I didn’t. I fell in love with language as a child, and used the words I came across quite unselfconsciously, as a beachcomber might blow into the shells he’s picked up on a stroll along the seaside. But in the process, I found I had inadvertently acquired a rather inflated reputation as a vocabularist. Such reputations tend to build gradually, but mine reached escape velocity with a specific tweet. Incensed by a libellous TV programme about me, I had tweeted that it was ‘a farrago of distortions, misrepresentations and outright lies broadcast by an unprincipled showman masquerading as a journalist’.

These were all words I had flung about with abandon in my debating days at St Stephen’s College, Delhi, but for some reason this sentence did not just strike a chord but triggered an almighty wave of enthusiastic curiosity on the internet. The Oxford English Dictionary even recorded in some puzzlement an unprecedented spike on its search engines, with over a million people, mostly in India, looking up the meaning of the word ‘farrago’ within the span of a few hours. My notoriety was established: I was India’s Mr Difficult Words.

From there it was a short step to being caricatured. Memes rolled off the versatile keyboards of those who seem to spend their creative juices entirely on web parody. Desi wits translated Diwali greetings and descriptions of bhel puri into logorrheic English and attributed them to me. A clever meme-maker put my tweet into the mouth of Captain Haddock, replacing his usual ‘billions of blue blistering barnacles’, while a taken aback Tintin responds, ‘Captain, I told you to stay away from that Shashi Tharoor fella!’

Photographs of my meeting the then home minister, Rajnath Singh, were modified to add a speech bubble above his head, saying ‘And I don’t even have a dictionary!’ While many of these were formulaic even if good-natured, the best was probably a rueful meme that stated, ‘I used to think I was poor. Now I’ve met Shashi Tharoor and I realise I’m impecunious.’

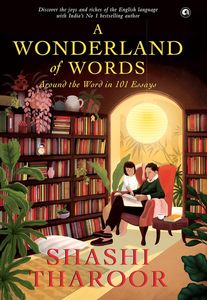

There are only two things you can do when a tidal wave of caricature descends upon you like this—either sulk crossly and reject any attempt to slot you into the jokers’ stereotypes, or embrace the caricature and try to turn it to your advantage. I preferred the latter course. I accepted an invitation to author a weekly column on words for the Dubai-based Khaleej Times. Many of these found wide circulation online, and the demand arose for a book. So here I am: my new book—A Wonderland of Words—has just been published.

Yes, words have always mattered to me. My father, Chandran Tharoor, was an immense influence on my life. After a village and small-town education in rural Malabar, he had moved to the UK in 1948 and relearned English from scratch. He was my teacher, guide, research adviser, imparter of values, my source of faith, energy, and self-belief. My enthusiastic approaches to life and learning are inherited from him; so is my work ethic—and my love for words. His great love of words and language, and the inventive ways my father put it to practise, inevitably rubbed off on his eldest child: me.

But it was never just words for their own sake. My father instilled in me the conviction that words are what shape ideas and reflect thought, and the more words you know, the more precisely and effectively are you able to express your thoughts. Hence a book on the wonderland of words, often a source of fascination—and indispensable for communication—seemed not such a bad idea after all. I hope my readers will agree.

editor@theweek.in