Emperor Krishnadeva Raya once decided to invade Bijapur. The sultan of Bijapur, knowing he couldn’t fight the Vijayanagara army, sent a smart and young astrologer to the Raya's court. The soothsayer impressed the king and courtiers with his glib talk, and drew the king into asking him how the planned war would fare. The fellow then pretended to read the royal horoscope, drew a grim face, and said the stars weren’t favourable.

The Raya was dismayed, as were his courtiers who were preparing for war. Then walked in the fabled jester Tenali Rama, actually a wise man like all jesters in the courts of the orient and the plays of Shakespeare. Rama suspected the astrologer to be an enemy agent, and began quizzing him. “Can you predict your own death?” Rama suddenly asked. The astrologer replied: “As per my calculations, I shall live up to 90.” The next moment, Rama drew his sword and cut the fellow’s head. Horrific, but everyone took it as the price for violating the shastras.

Astrologers say they can’t predict their own futures, though M.J. Akbar tells us in After Me, Chaos that emperor Humayun did. He foresaw his own death. Be that as it may, satvic jyotishis warn that if anyone can read one’s own future, one shouldn’t speak it out or seek to alter it through parihara kriyas. Humayun did neither.

Star-gazers have an earthy reason for forbidding self-prediction. Personal emotions, biases and desires could cloud your vision, leading to inaccurate predictions.

That’s what happened to Prashant Kishor. Though not an astrologer, he seemed to have been foreseeing how parties would fare in polls, and making a living out of suggesting electoral and political parihara kriyas that would ward off the doshas visiting them. Thus he is said to have strategised more than half a dozen electoral wins, including Narendra Modi’s in 2014.

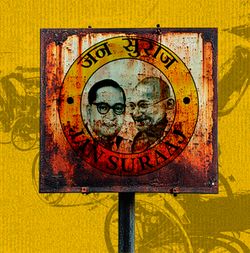

But as Humayun failed in predicting the fate of his own battles, Kishor failed in foreseeing the outcome of his own election. His Jan Suraaj, launched three years ago, failed to win a single seat, and 236 of its 238 candidates forfeited deposits.

Kishor’s big mistake was to confuse strategist with leader. He was a strategist, never a leader. He had no masses to lead—neither the forwards nor the backwards, neither the majority nor the minorities, neither the moneyed nor the jobless, neither the middle class nor the low class, neither the conservative nor the liberal, neither the rightist nor the leftist. A few from every one of these classes agreed with what he said, but they were just a few among the chattering gatherings, scattered across Bihar—a few thousand jobless, a few thousand who were piqued by the liquor ban, a few thousand who were cross with corruption.

Vote for your kids, he said, meaning vote for the future; but Biharis were concerned about their present. They wanted MLAs who could get their sons freed from the thana, MLAs who could call the bank and get them a loan, MLAs who could call the collector and get their land freed from the moneylender. Kishor didn’t appear to them as one who could.

He talked principles, but gave tickets to turncoats. He had no ideology. Arvind Kejriwal may have come to power sans ideology and stayed in power for a decade, but that was in urban Delhi where there are more piqued persons than mobilised masses.

And then a fatal flaw. He ran away from the battle when it was to be joined. He had threatened to take the field at Raghopur against Tejashwi Yadav, then backed off to his strategy room.

In the end, Kishor cut the sorriest figure in the Bihar round of 2025.