Sick of listening to the Gen X talking about sex and the new sexual mores most of the time, a colleague once exclaimed: “These kids of today think they discovered sex.”

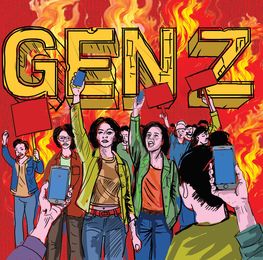

Much the same about the Gen Z. The way our commentators are toasting them for having led the revolts in Colombo, Dhaka and Kathmandu that led to change of regimes, one would think these kids discovered revolution.

No grudges. The Gen Z deserves credit for storming the palaces of sin where the ruling elite had been indulging in their orgies of wealth, and for effecting regime changes that wouldn’t have been possible through the democratic ballot. But the way commentators are making heady wordy cocktails for their celebratory toasts makes you think that the upsurges of the past had been led by pensioned persons of post-menopausal age.

Sorry to disappoint you, kids! Revolts of yore had also been led by young and virile men and women like you. They didn’t adopt any character of the alphabet to call themselves as you have, but it was the youth who led revolutions throughout history. George Washington was 33 when he opposed Britain’s Stamp Acts in American colonies. Georges Danton and Maximilian Robespierre were 30 and 31 when they spearheaded France’s notorious reign of terror. Vladimir Lenin may have been 47 when Russia’s serfs stormed the Winter Palace, but he had been active in the Bolshevik movement since 22. Jayaprakash Narayan may have been in his 70s when he called for total revolution, but it was Bihar’s college youth in their 20s who took to the streets on his call.

So it has been in Kathmandu, Dhaka and Colombo. It was the youth—Gen X, Y, Z, P or Q—who took to the streets and effected regime change.

What triggered their anger on Kathmandu’s streets was a ban on their little jobless pastimes—their reels, memes and trolls. Jobless and jealous (no offence meant) of the ‘nepo kids’ who were flaunting their politically powered parents’ ill-gotten wealth, they had been venting their pains and pangs in tik-toks, reels and mimes. Those passions burst forth when their little pastime apps were denied to them.

For all you know, K.P. Sharma Oli would have saved his job and government had he taken a leaf out of India’s Doordarshan managers of the 1980s. Whenever the Rajiv Gandhi regime apprehended a riot in any major city, it got the DD, then India’s only TV channel that otherwise telecast notoriously unwatchable programmes, to show a vintage Bollywood hit that kept the rabble-rousers glued to TV sets. On Sunday mornings in the late 1980s, India’s town streets looked like Covid-hit cities of three years ago—no shops, no traffic, no pedestrians, no pickpockets. Everyone and his mamashree were watching the Ramayana serial.

The long and short of the Sunday serial and cinema story is this—that the youth need pastimes as much as they need jobs. If Karl Marx thought that the capitalist order kept the labouring masses opiated with religion, the apps have been keeping the Gen Z sedated in the joblessly growing economies of the 21st century.

This is not to belittle the anguish of the Gen Z. Their pains are genuine, anger justified, and action righteous. To be fairer, they are better behaved than many of the celebrated revolt leaders of history. If the youth of France let loose a reign of terror, the Gen Z of Kathmandu, Dhaka and Colombo allowed institutions of their constitutions to take over.

Horace Walpole exclaimed in fear at the onset of the age of revolutions: “Our supreme governors, the mob.” Not in Kathmandu, Dhaka or Colombo.

prasannan@theweek.in