The president swears in all Union ministers to oaths of office and secrecy. But in 1998, the PM House witnessed a strange swearing-in, where the prime minister administered the oath of secrecy (not of office) to two men. One was Pramod Mahajan; the other was Jaswant Singh who passed away on Sunday.

Jaswant had lost the 1998 polls. The RSS, which had many grouses against the anglicised aristocrat (including his temerity to walk into their sanctified premises with his shoes on), insisted that no poll-losers be taken into the cabinet. So Atal Bihari Vajpayee, who wanted to confide in Jaswant and Mahajan matters of governance and atom bomb tests, swore them to secrecy on the PM House lawns.

When the world came down on bomb-maker India like a tonne of yellow cakes, Vajpayee sent Jaswant to Washington to ‘interlocute’ with deputy secretary Strobe Talbott. Soon, Vajpayee got Jaswant into the Rajya Sabha and made him de jure foreign minister. Talbott, who met Jaswant at 10 locations in seven countries, was so overwhelmed by Jaswant’s deft diplomacy as well as Victorian English, British manners, booming voice and military demeanour that he showed this specimen from the pre-World War era to his wife. She cooked a dinner for Jaswant.

Jaswant had also sent Vajpayee on a bus to Lahore, apparently to tell Talbott and the world that the atom-armed neighbours could also make peace. Sadly, the bus mission got hijacked to Kargil heights by Pakistan’s commando-general Pervez Musharraf.

That was the problem with Jaswant. He could not fathom diplomatic deception. He took everyone to be a gentleman like him who honoured a word given. So it was at Agra where he organised a Vajpayee-Musharraf summit with no agenda. The general came, and carpet-bombed the summit with Kashmir talk. Cabinet colleague Yashwant Sinha records in his memoirs that Jaswant had trusted the Pakistanis again and agreed to a draft joint statement that made no mention of the Shimla pact or cross-border terrorism. The summit crashed as L.K. Advani and Yashwant put their foot down, and the general took a midnight flight back home.

Vajpayee still trusted him, investing even the defence job with Jaswant when George Fernandes had to briefly stay out of the cabinet following the Coffingate. “I wish I had these two departments,” a jealous US secretary of state Colin Powell quipped.

Jaswant believed that Indians and India ought to carry their heads high. As finance minister later, he let every Indian carry up to $25,000 when flying abroad and spend in style, marking the beginning of capital account convertibility.

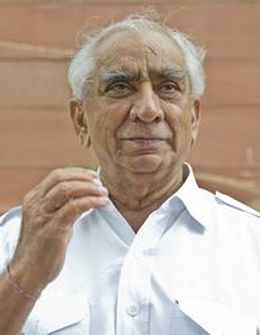

He held his head high always. Though he left the Army as a major, its cavalry culture stayed with him. He wore shirts with shoulder flaps that looked like epaulettes. He chose his words carefully—whether in diplomacy, in Parliament or a private chat—to achieve what the Victorian virtuoso of literature Matthew Arnold would have conceded was a ‘grand style’. Rarely would he mention a fellow-MP by name, but by the constituency he or she represented. In the house he was particularly fond of “the honourable member from Bolpur,” the communist barrister Somnath Chatterjee.

Once he used the style to put down Congress’s South Bombay MP Murli Deora, known for his ties with tycoons. He called Deora “the honourable member from Nariman Point,” much to the mirth of Deora himself.

Tailpiece: Jaswant met his match in a backbencher. As he ended a long-winded speech in his clipped English, someone quipped aloud: “Can we have an English translation of the speech, please?”