It was the fall of 1983. On my first visit to Paris, short on money but high on romance, I idled over a coffee in a wayside cafe in the Latin Quarter, alert to any artistic experience. The tempting smell of hot crepes filled the air and a heart-breaking riff from a saxophone spoke of the night before.

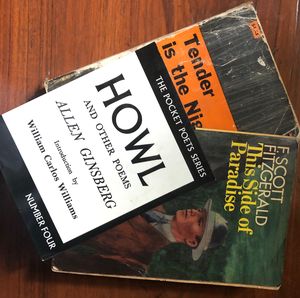

A bookshop with an irresistible name, Shakespeare and Company, soon beckoned. Encouraged by the welcoming owner, I wandered amid the crowded shelves of “Old Smoky Reading Room” but practical reasons of thrift drew me to the book bins outside the store. For 20 francs apiece, I picked up the Scribner editions of Fitzgerald’s Tender is the Night and This Side of Paradise. That was all, but I was hooked. Over the next four decades, I would visit the store every time life took me to Paris, searching I suspect not for any particular book but my lost youth. The owner, referred to in hushed whispers as simply George, was often around, a gentle towering presence.

Nicknamed Don Quixote of the Latin Quarter, George Whitman had come to study at the Sorbonne after World War II. Using his GI resources, he started a lending library with a thousand books, famously leaving his door open for anybody to drop in to borrow books. The lending library became Le Mistral, a bookshop on the Seine embankment where Paris-based writers like James Baldwin, Henry Miller and Anais Nin soon became regulars. Aspiring or nomadic writers—George called them Tumbleweeds—could get soup and a bed in exchange for a few hours of helping out. “Be not inhospitable to strangers, lest they be angels in disguise,” says a sign.

Sylvia Beach—who had run Paris’s original Shakespeare and Company bookstore post World War I, frequented by Hemingway, Joyce, Ezra Pound and Fitzgerald—recognised Le Mistral as a spiritual successor. With her blessings, George gave the famous name to his store on the bard’s 400th birthday in 1964, and later named his only daughter after Sylvia.

Among George’s early friends in Paris was a kindred soul, Lawrence Ferlinghetti, a naval veteran, poet, novelist and painter. Taking a leaf out of George’s book, he started City Lights in San Francisco, which too gathered writers, poets and painters, and reflected the warmth of its Parisian sister store; visitors are invited to “pick a book, sit down and read”.

A literary radical, Ferlinghetti worked to make art accessible to all and soon became the patron and soul mate of the leading lights of the Beat Generation—Allen Ginsberg, Jack Kerouac and William S. Burroughs. He was arrested for promoting lewd material when he published Ginsberg’s long poem Howl. The ensuing trial ended in a victory for Ferlinghetti and freedom of speech, besides giving a huge publicity boost to the Beats. His own poetry, particularly the collection A Coney Island of the Mind, sold phenomenally well, though he never regarded himself as one of the Beats, rather the last of the Bohemians.

In 2001, on my first visit to San Francisco, I tiptoed my way up to the upper storey of City Lights, where a literary event was under way. An elderly man was reciting poetry, an entranced group listened, a young woman sobbed into a white handkerchief. It was Lawrence Ferlinghetti. I slipped away after a while, not quite knowing how to make better use of the occasion. My copy of Howl and Other Poems now nestles next to the two Fitzgeralds bought in Paris on a select shelf.

George Whitman died in 2011 at 98 and Lawrence Ferlinghetti passed away early this year aged 101, both blessed no doubt by many angels in disguise.