Even as the lockdown is easing, there are doubts whether the new-found initiatives of several Central ministries will sustain when normalcy returns. The much-hyped claim of the human resource development ministry on the switch to online education has got a reality check as schools and colleges are reporting that they are not able to provide substantial coverage, especially in villages and impoverished urban centres.

The Centre’s BharatNet programme has claimed near-total optic fibre connectivity in the country, but its next phase—covering every home and individual—has a long way to go. In Delhi, the Aam Aadmi Party government’s promise that the city would be a ‘Wi-Fi metropolis’ remains unfulfilled, with only a small part of the city having dependable connectivity. Even cities known as tech hubs—Bengaluru, Hyderabad, Pune and Gurugram—do not have cheap or free connectivity for all residents.

While bureaucrats advised schools and colleges to switch to online classes during the lockdown, the experience of government and corporation-run schools has not been encouraging in many states. Teachers themselves have not been trained to give their classes online and managing a remote class scattered across multiple locations has been challenging. Even several universities have said that they have not been able to achieve maximum reach, and have advocated opening physical classrooms.

Though demonetisation increased digital currency, the dependence on cash has not come down. Similarly, if online classes increase, experts feel a huge budget and time would be required to move education online. Apart from connectivity issues, there is a lack of affordable and compatible hardware across the student spectrum. Some experts feel that relying on the internet for education may widen the social gap, unless the government supplies computers to needy students.

The UPA government had launched a programme for supplying a tablet, costing 010,000, to each student, but the project did not take off. The NDA government did not think of it as a viable option. Similarly, the enthusiasm of some state governments to supply free laptops, like the Akhilesh Yadav government in Uttar Pradesh, was not followed up by successive regimes. There is an argument that smartphones can do the job, but school managements and teachers’ associations are sceptical.

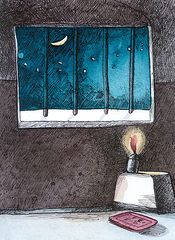

There are also doubts about the overall development of children if they are confined to homes, and lack contact with teachers, who inspire, guide and correct. The demand for a total switch to digital education would need a national debate, as the recent Kasturirangan report on national education policy did not consider in detail the pros and cons of switching over to digital education. Even this one-year-old draft report is yet to be considered and adopted by the government. There are concerns about the commonality of digitally prepared curriculum, providing remote laboratories for science subjects for every student, and extracurricular activities.

Another issue is the extreme enthusiasm for keeping labour laws in abeyance in some states in the wake of the lockdown as the governments did not hold extensive dialogues. While some of the laws have become antiquated because of the fast changes in manufacturing, services and society itself, the migrant crisis has exposed the perils of multi-layered subcontracting, especially in construction and road-building projects. There is a clamour that such far-reaching changes should not come as reactions to a pandemic, but after informed and time-bound public discussion, including debates in Parliament and the Lok Sabha. The haste to strike when the country is in lockdown can make the hammer miss its mark.

sachi@theweek.in